|

To see long excerpts from “The Brothers” at Google Books, click here.

|

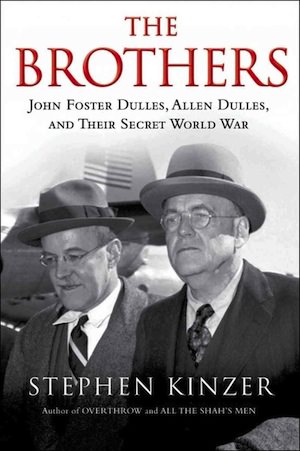

“The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles and Their Secret World War”

A book by Stephen Kinzer

Stephen Kinzer’s “The Brothers” tells the story of two siblings who achieved remarkable influence, serving as secretary of state and director of the Central Intelligence Agency in the Eisenhower administration. It is a bracing, disturbing and serious study of the exercise of American global power.

Kinzer, a former foreign correspondent for the New York Times, displays a commanding grasp of the vast documentary record, taking the reader deep inside the first decades of the Cold War. He brings a veteran journalist’s sense of character, moment and detail. And he writes with a cool and frequently elegant style. The most consequential aspect of Kinzer’s work is his devastating critique of John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, who are depicted as jointly responsible for acts of extreme geopolitical myopia, grave operational incompetence and misguided adherence to a creed of corporate globalism.

The Dulles brothers’ grandfather briefly served as secretary of state to President Benjamin Harrison. Their father, the Rev. Allen Macy Dulles, was a preacher and theologian who reared his boys to embrace missionary Christianity. Yet it was via Wall Street and the law firm Sullivan & Cromwell that both Dulles brothers ascended to power in Washington.

The elder brother, known as Foster, “thrived at the point where Washington politics intersected with global business,” Kinzer writes. At age 38 he became the sole managing partner of Sullivan & Cromwell. “Thus began his quarter century as one of the American elite’s most ruthlessly effective and best-paid courtiers.”

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA, Allen Dulles was among its first senior officers. Allen had spent a decade at the State Department before accepting his brother’s offer to join the global legal practice at Sullivan & Cromwell and then serving in the OSS. He was dispatched to Switzerland, where his circle of relationships included the seminal psychoanalytic theorist Carl Gustav Jung, who was commissioned to prepare psychological profiles of Hitler and other Nazi leaders.

Foster was stridently moralistic, but cunning and strategic in international commerce. Allen was facile and charming, a seemingly pathological womanizer with a lifelong passion for the ethos of espionage. “From a client’s perspective,” Kinzer writes, “they made an ideal team: one brother was great fun and a gifted seducer, the other had uncanny skill in building fortunes.”

Foster served as a foreign policy adviser to his friend Thomas Dewey, the governor of New York and a perennial presidential candidate, and emerged as a Republican Party mandarin and leading spokesman on major issues of the day. He denounced the rise of global communism, condemning its “diabolical outrages” and ideology of “evil, ignorance, and despair.” Foster became an avid critic of Stalin’s essays and speeches, keeping half a dozen copies of them in each of his various dwellings. His ritualized invocations of the communist threat induced despair among some liberal commentators. “The outlook for world peace,” one pundit wrote, “seems to be getting dull, duller, Dulles.”

With the election of Republican Dwight Eisenhower as president in 1952, Foster finally secured the job he coveted: America’s premier diplomat. Allen, who had joined the recently created CIA in 1951, was selected by Eisenhower to be its director. Never before or since — not even during the tenure of national security adviser McGeorge Bundy and his brother, William, an assistant secretary of state — had two siblings enjoyed such concentrated power to manage U.S. foreign policy.

Kinzer’s history acknowledges that Eisenhower sought to continue the “Grand Strategy” of containment, through which the United States would attempt to constrain — but not necessarily reverse — the growth of global communism. As commander in chief, Eisenhower “combined the mind-set of a warrior with a sober understanding of the devastation that full-scale warfare brings,” Kinzer writes. “That led him to covert action. With the Dulles brothers as his right and left arms, he led the United States into a secret global conflict that raged throughout his presidency.”

According to Kinzer’s reconstruction of the Eisenhower era, the president was an enabler of the Dulles brothers’ obsession with six different nationalist and communist movements around the world that would provide successive case studies in the potential of covert action and its pronounced limitations.The first test came in Iran, where nationalist Mohammad Mossadegh became prime minister in 1951 and swiftly moved to nationalize Iran’s oil industry, seizing control of the country’s petroleum wealth from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a primarily British enterprise. Operation Ajax, designed to oust Mossadegh, initially floundered. But the CIA paid street mobs to terrorize Tehran and recruited dissident military units that converged on Mossadegh’s home on Aug. 19, 1953. After a battle that killed hundreds, the Mossadegh government was overthrown. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was installed, “ruled with increasing repression for a quarter century, and then was overthrown in a revolution that brought fanatically anti-Western clerics to power.”

The CIA next, in 1954, deposed Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz, a former defense minister and leftist political reformer who expropriated nearly 400,000 acres of land owned by the powerful United Fruit Company. Arbenz represented a potent threat comparable to Mossadegh and his seizure of Iran’s oil assets. “Their crackdown on corporate power led Foster and Allen to presume that they were serving Soviet ends,” Kinzer writes. “Two reasons for striking them — defending corporate power and resisting Communism — blended into one.”

These early victories in covert action were followed by a series of failed or unnecessary interventions that the author attributes to the brothers’ hubris and incompetence. In Vietnam, the communist and nationalist leader Ho Chi Minh proved to be as resilient and relentless an adversary as the United States ever confronted. In Indonesia, the American effort to unseat neutralist President Sukarno constituted one of the largest covert operations of the 1950s but also ended in failure.

In the African nation of Congo, a charismatic former postal clerk named Patrice Lumumba became leader after the end of Belgian colonial rule. The CIA perceived him as sympathetic to Moscow and in 1960 helped the Congolese military depose him. Lumumba was then abducted, beaten and murdered by his political rivals and Belgian police. Only 200 days separated his inauguration and his death.

The Bay of Pigs operation remains among the greatest debacles in CIA history, an epic mess for which Allen Dulles was eventually fired. By the time 1,400 American-sponsored Cuban exiles blundered ashore in April 1961 in an effort to spark a spontaneous revolution, their mission had already been exposed. Months before, a New York Times headline had blared: “U.S. Helps Train an Anti-Castro Force at Secret Guatemalan Air-Ground Base.”

Allen had a pattern of delegating operational responsibilities to a dangerous degree, in this instance entrusting the fate of the invasion to his deputy, Richard Bissell. Both men were mired in abject denial about the operation’s prospects. A Marine Corps amphibious-war expert advised them that the United States would “be courting disaster” if it did not neutralize Cuban air and naval assets by providing “adequate tactical air support.” Yet Allen and Bissell knew that a newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy had ruled out any intervention by U.S. forces, the precise condition upon which the invasion’s success depended.

Allen Dulles’ “mind was undisciplined,” Kinzer concludes. “A senior British agent who worked with him for years recalled being ‘seldom able to penetrate beyond his laugh, or to conduct any serious professional conversation with him for more than a few sentences.’” Kinzer is similarly blunt in his assessment of Foster’s intellect, quoting Winston Churchill’s disparaging verdict that the secretary of state was “dull, unimaginative, uncomprehending.”

The author asserts that the Dulles brothers suffered from a form of sibling groupthink. “Their worldviews and operational codes were identical,” Kinzer writes. “Deeply intimate since childhood, they turned the State Department and the CIA into a reverberating echo chamber for their shared certainties.”

Gordon Goldstein is the author of “Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam.”

©2013, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.