‘The Boat Rocker’: An Unsettling Book About the Moral Dimensions of Modern Journalism

How timely it is to read this strange, intense novel from Ha Jin about the glories and limits of the press A former soldier in the Chinese army who chose to stay in the US after the Tiananmen Square massacre, Ha Jin has lived and worked under two very different sets of rules A former Chinese army soldier who chose to stay in the U.

Pantheon

|

To see long excerpts from “The Boat Rocker” at Google Books, click here. |

“The Boat Rocker” A book by Ha Jin

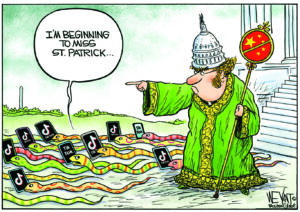

Americans already held little respect for journalists before this presidential campaign dragged their faith to all-time lows. But for all our grousing about bias, corporate concentration and the eye-crossing inanity of what passes for news, the First Amendment still allows us to express ourselves with a presumption of freedom unimaginable to many people around the world. The question of how that precious liberty should be exercised has never seemed more pertinent.

How timely, then, to read this strange, intense novel from Ha Jin about the glories and limits of the freedom of the press. A former Chinese army soldier who chose to stay in the United States after the Tiananmen Square massacre, Ha Jin has lived and worked under two very different sets of rules. He knows the Communist Party’s elaborate control of mass media just as well as he understands the free market’s complicated influence on what we read and watch. That bifocal vision brings uncanny depth to his eighth novel, “The Boat Rocker,” which should find its place alongside Janet Malcolm’s “The Journalist and the Murderer” as one of the most unsettling books about the moral dimensions of modern journalism.

The story is narrated by a young Chinese expatriate named Feng Danlin, who works in New York. He’s one of about a dozen reporters at the Global News Agency, a thorn in the side of the Communist Party that appeals primarily to Chinese people living abroad. As a journalist about to become a U.S. citizen, Danlin is infused with a convert’s passion — and self-righteousness: “I was the one known for my exposes,” he tells us, “shining a light onto the towering corruption of Chinese politics and media in my regular column. My acid tongue was legendary, my comments heart-stabbing, my views uncompromising, and my predictions sometimes even oracular.”

If the true influence of his columns is questionable, the purity of his principles is not. Having escaped a withering job at a state-owned newspaper in Changchung City, Danlin now writes under the blinding light of his personal credo: “Honesty is strength.” He defends his independence and integrity vociferously, insisting that “any equivocating must be cast out.” In this great country, he reminds a Chinese critic, “people go by rules, and reporters publish the truth.”

A more cynical — or melodramatic — novelist would set about demonstrating Danlin’s gradual corruption in his ridiculously idealized homeland, but Ha Jin has something more complicated in mind. As the story opens, Danlin receives an assignment to expose the truth behind a romance novel called “Love and Death in September.” From what we hear, the book sounds something like “Fifty Shades of 9/11,” a bodice ripper about a beautiful Chinese woman who loses the love of her life in the twin towers. For mysterious reasons, the book arrives under an absurd flutter of positive publicity: an endorsement from George W. Bush, a lucrative Hollywood contract, publishing deals around the world and full support from the Communist Party, which is pushing the novel as an embodiment of “the cooperative spirit between the United States and China.”

Danlin’s editor is sure that this romance novel is part of a larger scam being perpetrated by the Communist Party. But what’s most alarming to Danlin is that the celebrated debut novelist is his ex-wife, Yan Haili, the woman who handed him divorce papers the day he arrived in the United States.

Can the most principled journalist in America expose his ex-wife’s fraudulent novel without letting his still smoldering fury get in the way? (Spoiler alert: No.) But it’s not just his naivete about his own purity that thwarts him. He’s equally naive about the long reach of the modern Communist Party, empowered by its many billions of dollars, and he fails to understand the way racism will always curtail his efficacy in the United States.

There’s a darkly comic element to all this, delightful to see in Ha Jin’s work, which has typically been marked by extraordinary solemnity and restraint. Here, he expands his tonal range and approaches a kind of Kafkaesque absurdity. In what universe would a Chinese romance novel recast U.S.-Chinese relations? Indeed, the whole novel takes place in a slightly stiff and artificial realm of bold statements and disproportionate responses.

“This is America and I’m a journalist,” Danlin persists in reminding us as he’s drawn further into this ridiculous controversy. “My profession requires me to be honest with the public and always report the truth.” Grand sentiments, to be sure, but this awkward assignment keeps twisting on him, aggravating him toward grander fits of righteousness and broader acts of humiliation. At one point, he publicly defends his sexual potency. While his ex-wife warns him, “Truth depends on how you shape and present it,” for Danlin such relativism is anathema. Rocking the boat is not just a right; it’s a sacred duty — no matter where it leads.

Aside from a delicious satire of book publicity — an industry so unhitched from reality that it’s hard to parody its exaggerations — “The Boat Rocker” also dramatizes the vast shadow world of internet news. The novel’s most illuminating moments explore the swirling crosscurrents of reporting, opinion, propaganda and reader comments that breed largely outside the American mainstream media but are of intense interest to foreign governments and expatriates eager to influence public perception.

As Danlin pursues the story behind his ex-wife’s tawdry novel, he gets caught in the confluence of American capitalism and Chinese influence. In the United States, free speech may not be limited the way it is in China, but there are limits nonetheless. “I wonder,” he muses at one point, “if I might turn out to be the only loser in this scandal. Sometimes the whistleblower blows so hard he busts his own bladder.”

That may sound like a foreshadowing of doom, and certainly Ha Jin’s previous novels have given us plenty of reason to anticipate a bleak finale. But this story and this tenacious reporter will surprise you. Yes, Danlin’s tone gradually cools and he loses his fiery overconfidence, but the way he clings to his disruptive mission leaves us asking what is required and what is expected of our modern-day truth-tellers — even in America.

Ron Charles is the editor of The Washington Post Book World.

©2016, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.