The 2015 SCOTUS Awards: A Look Back at the Highs, Lows and Yearly Shenanigans of the Supreme Court

Justice Antonin Scalia earned his stripes as the court’s loosest cannon for his remarks on Obamacare and same-sex marriage, while Justice Clarence Thomas was honored for making it through his ninth year without asking a single question during oral arguments. Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia in Washington in 2010. (Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

1

2

3

4

5

Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia in Washington in 2010. (Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

1

2

3

4

5

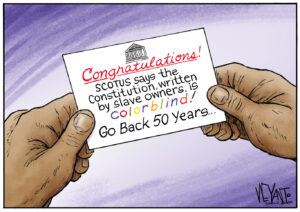

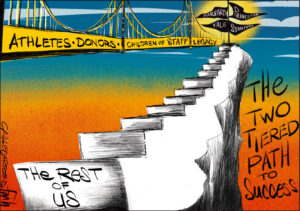

Presaging more madcappery for the court’s current term, Scalia registered another tour de force during the oral arguments held this month on affirmative action in Fisher v. University of Texas. After asking whether black students might perform better at “slower-track school[s] where they do well” rather than at top colleges like Texas, Scalia mused that black scientists in fact tend to “come from lesser schools where they do not feel that they are being pushed too hard in classes that are too fast for them.”

Well done, Nino (as his friends and admirers call him). You’ve gone platinum.

SUPPORT TRUTHDIG

The Gold Medal for Keeping the Death Penalty Alive

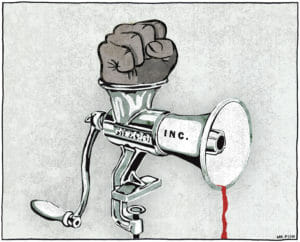

The award goes to Samuel Alito for his 5-4 majority paean to capital punishment in Glossip v. Gross. At a time when the civilized world is turning away from the death penalty and in a year when only six American states handed down capital sentences, Alito embraces the ultimate sanction with the same kind of unswerving passion he devotes to the dismantling of public-employee unions. As I have written previously, Richard Glossip — the plaintiff in the Glossip case — was convicted of a 1997 murder in Oklahoma but may very well be innocent. Technically, the issue before the court in his case is not his guilt or innocence but whether the state’s use of a new and highly controversial three-drug cocktail in its lethal injection protocol violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. Alito’s majority opinion, joined by the court’s other Republican appointees, answered the issue with a ringing endorsement of the protocol, despite the fact that the cocktail had caused prolonged agony in two previous executions. Alito’s decision, as Steven Schwinn — an associate professor at the John Marshall School of Law in Chicago — has charged, was an exercise in circular reasoning that established a new set of “Wonderland rules for method-of-execution claims.” “Because capital punishment is legal,” Alito wrote, “there must be a constitutional means of carrying it out.” Surveying the history of the death penalty, Alito added that while methods of execution (from hanging to electrocution, firing squads, lethal gas and injections) have changed over the years, the Supreme Court “has never invalidated a State’s chosen procedure.” Nor was the court about to shift gears in the year of Our Lord 2015 for Richard Glossip. In a ruling that will have profound ramifications for future death-penalty cases, Alito created an almost impossible bar for condemned prisoners to surmount, requiring them to show both that any challenged means of execution “presents a risk that is sure or very likely to cause needless suffering” and that there are “feasible, readily implemented” and less painful alternatives available to the states for putting them to death. In other words, design your own demise, or stay out of court. Either way, you lose.The Gold Medal for Questioning the Death Penalty

This prize goes to Justice Stephen Breyer for his dissent from Alito’s majority Glossip opinion. Writing for himself and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Breyer not only would have granted Glossip’s petition (which had been filed for him and several other Oklahoma prisoners facing imminent execution), but he would have taken another, far bolder, step calling for a re-examination of the death penalty itself. “[R]ather than try to patch up the death penalty’s legal wounds one at a time,” he wrote, “I would ask for full briefing on a more basic question: whether the death penalty violates the Constitution.” Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.