Thank You, Peter Matthiessen, for Taking Me Along

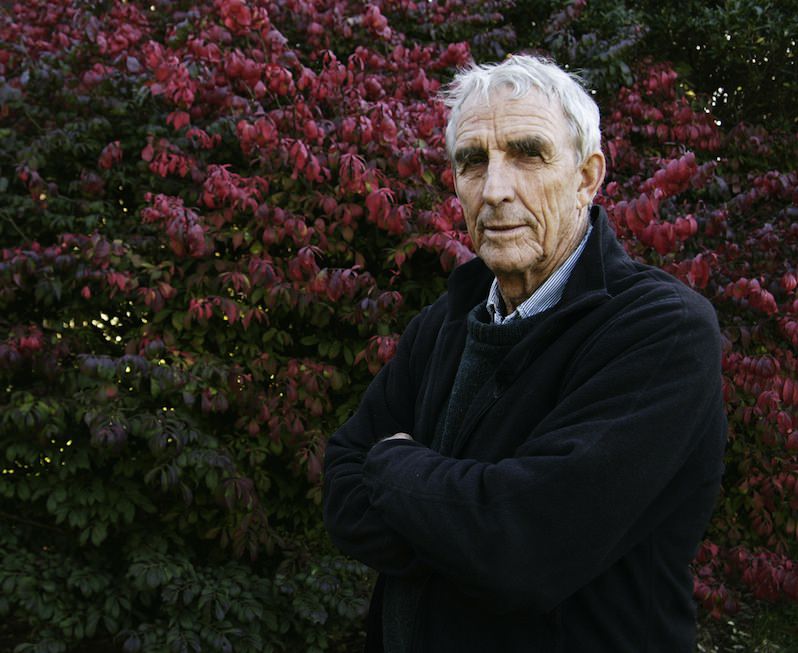

I trekked with the writer, who died last week, only in a Walter Mitty dream, but his service as a guide was valuable. AP/Ed Betz

AP/Ed Betz

AP/Ed Betz

Peter Matthiessen was my guide, and I once went on a wonderful journey with him in Nepal.

Were he alive to read that sentence, the novelist, naturalist and Zen priest surely would have reacted with an emphatic “Huh?” … because he and I never met. I trekked with him only in a Walter Mitty dream he inspired in me.

In the real world, we would have been likely to meet only if he had frequented the inner chambers of metropolitan newspapers where I labored, and not the literary salons, sweeping savannahs and breathtaking mountains where he spent much of his life. My connection to this extraordinary person was solely through the elegant, lyrical words he wrote in one special book, “The Snow Leopard,” a true account of a long hike.

I’m ashamed to reveal my provincial ignorance, but I must admit I had never even heard of Matthiessen until 2013 when a public radio broadcast praising the 1978 book prompted me to go to eBay and shell out $3.99 for a used copy, a purchase made exactly one year before the day on which I am writing this. Although I have seen a number of articles and videos about Matthiessen, “The Snow Leopard” is the only book of his that I have read. All of which means that if you are looking for an expert assessment of the life and works of Peter Matthiessen you will not find it in this brief essay. My only credentials for writing about him come from the fact that “The Snow Leopard” touched me in a lasting way and I often turn to it when I find myself snarled in feelings that reality is too crude, too cruel.

Matthiessen died Saturday of leukemia at 86 on Long Island, N.Y., where he lived. The Los Angeles Times marked his passing with an obituary of more than 40 column inches and an entertainment-section tribute of roughly the same size. The passing of the tall, sharp-featured adventurer shared the pages of the L.A. Times that day with reports on the death of a short, soft-faced icon of American movies, Mickey Rooney.

Matthiessen served in the U.S. Navy, was a student at Yale and the Sorbonne, co-founded the literary magazine The Paris Review and won the National Book Award three times, once for “The Snow Leopard”; he is the only winner in both the fiction and the general nonfiction categories. Matthiessen also found time to produce more than 10 nonfiction titles and more than 20 books of fiction. And along the way he had a stint as a young spy for the CIA, traveled in Asia, Australia, Africa, North and South America, New Guinea and Antarctica, and championed oppressed peoples, indigenous populations and the beasts of sky, sea and land, along with the rest of the glorious natural world. This was a man of many parts.

“The Snow Leopard” is a monumental tale of Matthiessen’s 1973 trek with zoologist George Schaller in the high country of northwest Nepal, an expedition that Schaller undertook to study the bharal, a creature that looks like a sheep and acts like a goat. Matthiessen hoped to see the famously secretive leopard on the expedition. He writes that when he received Schaller’s invitation, “the hope of glimpsing this near-mythical beast in the snow mountains was reason enough for the journey.” However, a more important mission developed for Matthiessen, one set forth in a line on the cover of my paperback copy: “The astonishing spiritual odyssey of a man in search of himself.” It is no news for Matthiessen fans when I say that the writer never set eyes on a snow leopard. However, he did meet ghosts of his own psyche, including that of his relationship with his second wife, who had died the previous year. The journey covered as much interior ground as it did physical terrain. One reason I esteem Matthiessen is his empathy, which springs off his pages. This adventurer — a child of privilege who chose to do hard things as an adult — sees suffering but does not let it poison him. “Confronted with the pain of Asia,” he writes, “one cannot look and cannot turn away. In India, human misery seems so pervasive that one takes in only stray details: a warped leg or a dead eye, a sick pariah dog eating withered grass, an ancient woman lifting her sari to move her shrunken bowels by the road. Yet in Varanasi [India] there is hope of life that has been abandoned in such cities as Calcutta, which seems resigned to the dead and dying in its gutters. Shiva dances in the spicy foods, in the exhilarated bells of the swarming bicycles, the angry bus horns, the chatter of the temple monkeys. … The people smile — that is the greatest miracle of all.”

A reverence for human life, for animal life, for plant life, for the life of the planet.

What initially drew me to “The Snow Leopard” was Matthiessen’s ties to Zen Buddhism, a practice I had sporadically looked into over the years. The book is a primer of sorts on Buddhism, and between its covers Matthiessen writes often and movingly about his experience as a student of Zen.

A number of the sentences of “The Snow Leopard” glisten like Zen jewels. When I finished reading a Truthdig item on Matthiessen’s death, I began to go through the book again, marking some of those lines. I plan to copy the best into a computer file and then print out and frame a couple for display in my home work space. In times of frustration, they will be a comfort. Perhaps they will help me remember that each moment is what it is in that moment, regardless of how I might have it otherwise. Om Mani Padme Hum.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.