Terrorism by Any Name

What’s as interesting as Stack’s motives are our motives in labeling this act. Was Stack’s gesture an attention-grabbing suicide plot, a deliberate criminal act, an act of heroism or an act of terrorism? It seems that the answer varies according to whom we ask.Was Stack’s gesture an attention-grabbing suicide plot, a deliberate criminal act, an act of heroism or an act of terrorism?

“Nothing changes unless there’s a body count,” according to A. Joseph Stack III. On Thursday, Stack, 53, posted a suicide note on the Internet, burned down his house in Austin, Texas, and then flew a Piper Cherokee PA-28 into an IRS office, killing both himself and IRS employee Vernon Hunter and wounding 13 others. More and more is being revealed about Stack’s life story, including his rage and hatred for the IRS, the federal government and the Catholic Church. In the six-page manifesto that he posted he rails against many entities, including the American justice and educational systems, claiming they create a false sense of security and financial entitlement.

Perhaps nothing is as direct as his closing: “Well Mr. Big Brother IRS man … take my pound of flesh and sleep well.” Speculation abounds. ”I don’t know what to base his madness on. It must have been lurking beneath the surface,” Michael Cerza said in a New York Times interview. Cerza played drums, piano and trumpet with Stack in the Billy Eli Band.

But what’s as interesting as Stack’s motives are our motives in labeling this act. Was Stack’s gesture an attention-grabbing suicide plot, a deliberate criminal act, an act of heroism or an act of terrorism? It seems that the answer varies according to whom we ask. Stack’s friends and neighbors are stunned because he never discussed his anti-government feelings with them. They’re calling it suicide.

Some of his Facebook fans are calling it heroism. “Finally an American man took a stand against our tyrannical government that no longer follows the Constitution,” wrote Emily Walters of Louisville, Ky. Meanwhile, White House press secretary Robert Gibbs said: “… we don’t suspect that [foreign terrorism]. I am going to wait, though, for all the situation to play out through investigation before we determine what to label it.”

For his part, Nihad Awad, national executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, expressed a different perspective. Awad noted that “whenever an individual or group attacks civilians in order to make a political statement, that is an act of terror. Terrorism is terrorism, regardless of the faith, race or ethnicity of the perpetrator or the victims.”

Awad’s description is in line with federal policy. According to Section 802 of the USA PATRIOT Act (Pub. L. No. 107-52), a person engages in domestic terrorism if he or she does something that is “dangerous to human life that [is] a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State; [if the act appears] to be intended: (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping. … [Also, the acts have to] occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.” If they do not, they may be regarded as international terrorism. In other words, if an act is intended to strike with fear those against whom it is adopted and/or uses methods of intimidation (like flying a plane into a building housing a federal office) then it’s safe to call it terrorism. So, why the hesitation?

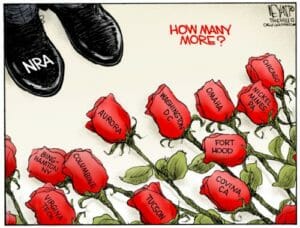

A look at some other similar acts and U.S. code on terrorism sheds light on the issue. Stack is clearly not the only angry American to lash out in recent history. The Southern Poverty Law Center found six cases of attacks targeting the Internal Revenue Service since the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. Americans seem to be angry about more than taxation and representation as the June 2009 incident at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., reveals. In that incident, white supremacist James von Brunn killed a security guard and injured two other people. Von Brunn’s attack happened on the heels of the shocking February murder of abortion provider Dr. George Tiller in a Wichita, Kan., church. Why haven’t these been labeled acts of terror? Might it have something to do with the fact that the U.S. Code definition of terrorism is limited to “subnational groups” or “clandestine agents”? Could this mean that some Americans are excluded from suspicion?

Hebah Farrag of the University of Southern California’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture says the answer, in short, is yes. “Had this act been committed by a man of a different color or religion the reports would have been cast in a much different light.” Farrag is also disturbed by sympathetic coverage of Stack compared to coverage of 9/11 hijackers and other assailants of Arab descent and/or Muslim faith. For Farrag “this double standard, obvious racism and bias in reporting is not only damaging, it is alienating. As a Muslim-American, while I am not surprised by this style of reporting, I am appalled, disappointed and feeling ever more alienated by a nation that seems to condone violence from certain elements of society which it considers to be acceptable and explainable.”

David Hino, pastor of The Light Christian Fellowship in Signal Hill, Ca agrees. Noting the strong opinion in some religious circles that Islam and the Koran support violence and murder to convert others, he says that “Islamic extremists are called terrorists. Muslims are not and should not be.” Comparing religious traditions, Hino explains that “in the Christian Bible, the Old Testament is filled with stories of violent elimination of nations as the Hebrews conquered the promised land. Given that same reasoning, right-wing extremists who advocate violence against the government are also terrorists. People who have a belief system that calls for killing people are terrorists.” For Hino and Farrag there should be no differential labeling or double standard.

Farrag’s and Hino’s views are supported when we look at the case of Maj. Nidal Hasan, who killed 12 people in November 2009 at Fort Hood in Texas. Hasan was immediately suspected of having links with Islamic extremism and terrorism. FBI agents investigated his family background and immigration history, and his alleged connection with Anwar al-Aulaqi, a radical imam at Dar al-Hijrah mosque, where at least two of the September 11 hijackers are said to have worshipped. It appears as though Hasan was quickly considered a terrorist for being disgruntled with the Army. Though his actions are no less inexcusable than Stack’s, Hasan did not get the same benefit of the doubt that Stack appears to be receiving.

Farrag went on to explain that Stack’s action is “clearly an act of terrorism, especially if reports on his suicide note are correct in which he states that ‘violence is the answer.’ While the media is consistently reporting this as an act by a ‘mentally ill’ and ‘disgruntled’ employee during a time of economic crisis, clearly this was a man who wanted to attack an arm of the U.S. government as well as American economic policy.”

According to Stack’s own note, the attack was not about his suicide. It was about anger. Hino says that after reading Stack’s manifesto it’s clear that his “belief system is only an outward expression of a greater problem that is rarely addressed — the anger or character of the person. We fail to see the anger of the person because we do not question it. We, the audience and public, see and/or think that the anger is justified.” This could account for the hesitation in labeling Stack a terrorist.

If Farrag and Hino are right, then Stack’s attack was as much about anger as it was about channeling anger into a set of beliefs that justified his assault on the U.S. government. After all, Stack was not using the plane as a flying mechanism; he was using it as a weapon. In light of this it can be argued that to call him a “pilot” is giving him an innocence he does not deserve. Perhaps we have not been willing to call this an act of terror because that label generally connotes “Arab” or “Muslim” or “foreign” or “angry radical” in the public mind. Perhaps calling Stack’s attack an act of terrorism, thereby putting the label of terrorist on a white, non-Muslim American, might take away from the fear of “terrorists” our nation is cultivating in its efforts to marginalize the Middle East and Muslims. Perhaps calling Stack’s act an act of terrorism is more terrifying than the act itself.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.