Stevie Ray Vaughan: Playing as If His Life Depended on It

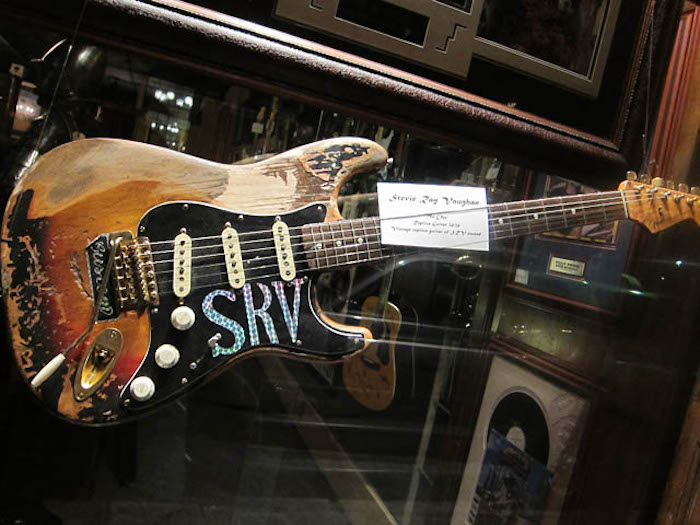

How did the guitarist become the unique artist he was? A new book answers that question with uncommon clarity and authority. Replica of Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Number One" guitar. (Jason Lam / Wikimedia Commons) (CC BY 2.0)

Replica of Stevie Ray Vaughan's "Number One" guitar. (Jason Lam / Wikimedia Commons) (CC BY 2.0)

“Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan”

A book by Alan Paul and Andy Aledort

Almost 30 years after his untimely death, guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan’s virtuosity is widely acknowledged, but his life and career remain difficult to place. For a Texas bluesman, Vaughan seemed too influenced by rock guitarists, especially Jimi Hendrix. And though his solo on David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” helped make that song a hit, Vaughan purposefully chose the blues, whose future was uncertain, over all other idioms. How exactly did Vaughan become the unique artist that he was? Alan Paul and Andy Aledort’s “Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan” answers that question with uncommon clarity and authority. Made up largely of direct quotations from those who accompanied, managed, or produced him, Vaughan’s story unfolds in surprising ways.

The temptation in such biographies is to make the subject’s success seem inevitable. Turning points are identified and cataloged, and though the story usually includes challenges and setbacks, it arcs inexorably toward greatness. But the interviews here temper that sort of mythmaking. We learn firsthand about the early gigs, shifting lineups, drug and alcohol abuse, and the vagaries of making it in the music business. And though “Texas Flood” reveals a series of transformative moments in Vaughan’s life, they are so contingent and inapposite that his success never seems predestined.

Vaughan was born in 1954 and raised in a scratchy part of Dallas. As a teenager, he dropped out of school, moved to Austin, and was known as Jimmie Vaughan’s talented younger brother. His first big opportunity came in 1976, when the owner of an Austin club begged the curmudgeonly Albert King to let Vaughan play with him. As Jimmie Vaughan said, “Nobody would ask Albert King to sit in unless you were dumb or something.” One eyewitness recalled, “Of course, Stevie just burned, like he always did. There was little Stevie up there with Big Albert killing it, and it really tickled Albert—and all of us. He started playing Albert King licks and doing it really good, and Albert looks down and shakes his head.” Another witness noted, “It really felt like a milestone for Stevie.”

Six years later, however, Vaughan was still grinding it out in local clubs. His manager sent a tape to Mick Jagger, and Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler heard Vaughan for the first time at a Texas club. It was, Wexler said, “almost an out-of-body experience.” He recommended Vaughan to the organizer of the Montreux Jazz Festival. “You gotta book this musician,” Wexler said. “I have no tapes, no videos, no nothing. Just book him.”

In April of that year, Vaughan auditioned for Rolling Stones Records by playing a private party in New York City. “As soon as Stevie started playing,” one spectator observed, “Ron Wood grabbed a chair, straddling it right in front of Stevie. He stared at Steve the entire time, hypnotized.” The label didn’t sign Vaughan because Jagger said blues albums didn’t sell well. But as Vaughan’s bandmate noted, “We were playing Skip Willy’s for four drunks, and all of a sudden Mick Jagger wanted us to play for him in New York. … This huge momentum seemed to be building.” Vaughan was impressed by another aspect of the trip. “I’ve never seen so much cocaine in all my life,” he told a friend in Austin. “I think Ron Wood had cocaine in every one of his pockets. And it was good shit—my heart was pounding!”

Vaughan’s set in Montreux went badly, but David Bowie asked to meet him in a bar and invited him to play on his next album. The next night, Vaughan was playing the same bar when Jackson Browne’s bass player walked in. He immediately called his bandmates and exhorted them to come. “We jammed until 7:00 a.m.,” Vaughan’s bandmate recalled. “When we were done, Jackson said that he had a studio in LA and we were welcome to come record tracks free of charge anytime.”

Both invitations were significant. Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” alerted fans and industry insiders to Vaughan’s talent, and a session at Browne’s studio produced “Texas Flood,” Vaughan’s first album. One admirer was Huey Lewis, who ran into Vaughan’s bandmate outside a hotel elevator, and later asked his manager to book Vaughan for his next tour. “It was all sold-out arenas, and that’s when things started taking off,” said the bandmate. Another observer likened that tour to Jimi Hendrix opening for the Monkees.

Paul and Aledort leave no doubt about Vaughan’s skill, compiling accolades from Gregg Allman, Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, Billy Gibbons, Buddy Guy, and other accomplished guitarists. The interviews also reveal the physical toll Vaughan’s style exacted on him. “He paid a price for being committed as he was to the kind of string bending he was known for,” said one insider. “He often had massive holes, like a quarter-inch deep, in his fingertips. Before shows, he would fill the holes with baking soda and put super glue over it.” After grafting a piece of skin on top of the hole, Vaughan would then “file it down smooth so it wouldn’t catch on the strings. He was very ingenious and inventive.”

“Texas Flood” is at its best on the subject of Vaughan’s chaotic personal life. He never kept a home, was careless with money, and abused drugs and alcohol for so long that he thought his music required it. That abuse also dominated his troubled marriage. At age 31, he was walking with a cane and blowing his solos, playing in the wrong key or in perfect time on the wrong beat. He later compared those performances to playing the guitar with boxing gloves. In 1986, he hit rock bottom in Germany, vomiting blood in his hotel room.

Everyone saw that—or something worse—coming. The real surprise was Vaughan’s later commitment to sobriety. “It didn’t occur to me that Stevie would really go clean,” said his brother Jimmie, who by that time was thriving with The Fabulous Thunderbirds. “I figured that he’d do his thirty days [in rehab] to get everyone off his back, then go back to it. But he was serious and dedicated, and he showed the way for me and a lot of other people.” Bonnie Raitt was struck by his personal and musical transformation:

He had a furnace in his heart and was the epitome of all that is dark and sexy, brooding and compassionate. The most extreme emotions of the blues and of life were in every breath he took. And to find out that he could maintain that while sober was just a revelation. If anything, he was covering more emotions. He was playing as if his life depended on it, and it did.

Vaughan’s bandmates also renounced drugs and alcohol, and the years that followed were remarkably happy and productive. Vaughan filed for divorce in 1987 and enjoyed a healthier relationship with his new girlfriend. Two years later, he released “In Step,” which won a Grammy. He also toured with The Fabulous Thunderbirds and reunited with his brother on “Family Style,” which appeared in 1990. But that idyll was destroyed when Vaughan perished in a helicopter crash after a performance in Alpine Valley, Wisconsin. Stevie Wonder, Dr. John, Bonnie Raitt, and Jackson Browne sang at his funeral.

The authors, both senior editors at Guitar World magazine, have covered similar ground before: Paul’s previous book, for example, documented the life and times of the Allman Brothers. But the authors give the last words to Jimmie Vaughan and Tommy Shannon, Stevie’s bandmate. “When Stevie played,” his brother writes in the epilogue, “his guitar talked and told his story. If you listen, you can hear it.” “Texas Flood” also tells that story—and captures the purity, simplicity, and expressive power of Vaughan’s music and message.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.