‘Star Wars: The Force Awakens’: Deep Down, a Product of Fear

It's unlikely that the beloved space saga's Episode VII -- regardless of whether it turns out to be a crowd pleaser -- has taken the risks George Lucas took with his installments.

Kylo Ren, a villain in “Star Wars: The Force Awakens.” (Lucasfilm)

A slightly different version of this piece originally appeared on Alex Ricciardi’s Facebook page.

“Star Wars: The Force Awakens” premieres in thousands of U.S. theaters this week. I’ve been reading reviews, and the one thing that seems to be unanimous is that it “feels like the old ‘Star Wars.’ ” I have to wonder if this is good. Some reviewers have been content to refer only obliquely to George Lucas’ prequel trilogy, while others have flat-out thanked Disney and company for restoring the franchise to its former glory, or “redeeming” “Star Wars” from Lucas’ fiasco.

In recent conversations with friends about Lucas and the prequel trilogy, I’ve realized that, over the years, my respect for the man has only grown. Let me explain.

His prequel trilogy is many things. Among the terms I would use to describe the films are: poorly acted, sterile, bloated, convoluted. However, I would also describe them as completely idiosyncratic, as the work of a singular mind—an auteur—and admirably moral works of art.

Many people see the prequels as a cynical cash grab, an easy way to empty the wallets of adoring fans. But the easy way would have been to make three films utterly steeped in nostalgia, films that follow the original trilogy’s structure beat for beat, that are near carbon copies of the originals with today’s technology swapped in. They would be three films with simple stories, unambiguous morals and likable, i.e. “bankable,” leads.

Lucas made choices that are mostly antithetical to the easy way out. In place of nostalgia, he gave us a universe with a decidedly different look and feel. In place of the relative structural simplicity of the original trilogy, he gave us ungainly works, stories that branch out in all directions and follow sidelines that sometimes border on nonsensical. In place of the Hero’s Journey, he portrayed a more complex path, showing how a good person can become a villain. And why did he do this? Perhaps because he cares about his child viewers.

Imagine you’re George Lucas. You’re planning a follow-up to what has become the defining work of your life. You’re the same George Lucas who began as an ardently political filmmaker, of the same ilk as Francis Ford Coppola (in fact, you originally developed “Apocalypse Now”), and you are the same George Lucas who turned away from political films because you decided it might be equally important to make movies that would remind people—children especially—that there was power in imagination, in fantasy, in allowing yourself to dream. You have toyed with the possibility of another “Star Wars” trilogy for years, and now finally seems to be the time to do it. You recognize this challenge as a heavy burden. When the first “Star Wars” film premiered, there was no indication that it would become a phenomenon. But now the whole world will be watching, including many, many children who are still developing their sense of right and wrong. You could probably write nearly anything in the style of the pulpy ’50s serial. Easier still, you could farm the writing out to any number of talented screenwriters who would jump at the chance. But you feel that you have a responsibility here. Your audience of children will one day grow up to run the world, and like all generations, they need myths and legends that imbue them with a sense of morality.

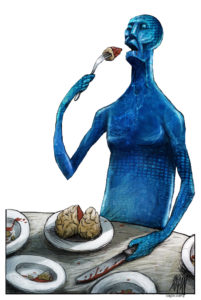

The prequel trilogy begins with a young boy who is likely as old as many of your new fans will be. He discovers he has the potential to be something far greater than he’d ever imagined. And by the end of the trilogy, this innocent, wide-eyed, intelligent boy named Anakin has become the villain of his own story. In an elegant thematic touch, the story of his descent closely mirrors the other major plot thread woven throughout the three movies: the fall of the Republic and the rise of the Galactic Empire. Lucas creates an all too real scenario wherein the Chancellor of the Republic, who has much power but not all of it, deftly orchestrates a false war with an imaginary enemy in an attempt to terrify the populace into voting their rights away. He convinces his public to give in to their fears, and in so doing, give up their autonomy, their democracy and their freedom. Not coincidentally, he uses the same tactics on Anakin, preying on his natural fear of death and his latent anger until they become a prison he cannot escape.

Lucas created a trilogy of massive-budget blockbuster films that have the power to teach a great lesson: As a class, our ruling elites want us to think we are weak and that they alone can protect us. They pretend to be our friends, they appeal to our vanity as they prey on our fear, magnifying it, molding it—and us—into a form they can control. Letting fear and anger drive us means losing ourselves.

This is not an easy theme. It doesn’t sell merchandise. But it’s important, especially now, as candidates for the White House foment fear and xenophobia left and right.Now, go back to 1999. “Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace” has been released to huge box office success and a decidedly mixed reaction. Its critics are more than vocal—they’re downright nasty. The same fans who grew up on the original trilogy, who wrote fan fiction, who played with toy lightsabers and brought their kids to see the new “Star Wars” film, are telling you that you had no right to make the film that you did, that you’re retroactively ruining your previous work. What on earth could compel you to keep going? After you poured your heart and soul into a work that, to you, was not only a movie but also a moral act? And you’ve promised them two more of these? Perhaps now you start to be overcome by your doubts. Perhaps you start to fear the backlash of your once-adoring fans, perhaps you consider capitulating, ceding your autonomy and your freedom in order to … but wait. Maybe you perceive that your fans are starting to sound like the Empire. Maybe you realize that you are ready to compromise your own integrity because you are afraid of losing their affection. But you believe in your heart that it is more important to make the work you believe in rather than the work they want.

Isn’t this what we want from our artists? Don’t we want storytellers, painters, composers and singers who follow their muse? Who stand in their integrity, critics be damned?

There is one area of the arts where we are stridently opposed to authorial integrity like this. It’s a segment of the film industry that Lucas helped to create: the blockbuster. We like to keep our art over here in one pile, and our blockbusters in another, and never the twain shall meet (“Mad Max: Fury Road” is one of precious few glorious exceptions that proves the rule). Commercial filmmaking is, in fact, antithetical to the idea of artistic integrity. Many of us drool over box office reports and hem and haw about how some irresponsible director didn’t earn his studio’s money back, at the same time bemoaning the lack of creativity and innovation within the medium. Like Alejandro Jodorowsky before him, Lucas dared to spend a lot of money on something meaningful to him—not something that would simply please fans, critics or investors.

It seems silly to spend so much time defending a man who has more money than most of us will ever see, several lifetimes over. It’s doubly silly because I don’t particularly like the prequels as films. But I believe that it’s important to recognize artists, especially those who try to make bold, daring works in an industry whose financial contours expressly discourage bold and daring works.

If art can be said to have anything as utilitarian as a “purpose,” I would venture to say that art is a tool of revelation, a tool for discovering a truth that has always been there. It is, as Jodorowsky would say, “the search for the human soul.” Lucas perceived a truth he wished to give to us. Specifically, a deep truth that he may believe could provide children with a moral framework with which to view their lives. He is not didactic about it; he simply tells a story of how the world can corrupt a person. And he says: This is one path. Here is one way your life could turn out. But it is not the only path.

I’ll see “The Force Awakens,” and I may even enjoy watching it more than the prequels, but I would be shocked if it is anywhere near as bizarre, ambitious or heartfelt as they were. My guess is that “The Force Awakens” will be a near-perfect, unassailable example of a quintessential crowd-pleasing blockbuster. It will be rated highly by critics and fans alike. And like too many universally beloved things, it will be, deep down, a product of fear, because I guarantee you that the Disney executives who paid $4 billion for the rights to “Star Wars” are terrified of doing anything to alienate its fans again. Well, congratulations everyone. The Empire won.

Alex Ricciardi is the editor and associate producer of the Oscar-shortlisted documentary “Jodorowsky’s Dune” and a founding partner of the New York-based production company Endless Picnic.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.