‘Spotlight’ Film Review: A Paean to Big-City Print Journalism in Its Twilight

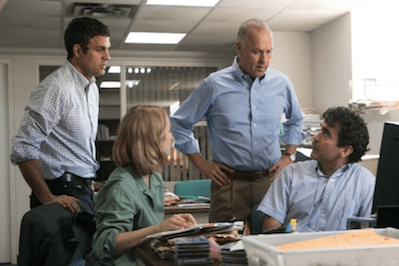

Writer-director Tom McCarthy's stirring drama celebrates old-fashioned newspaper investigation by telling a real-life story: how The Boston Globe exposed child abuse among Catholic priests. From left: Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams, Michael Keaton and Brian d'Arcy James in "Spotlight." (Open Road Films)

From left: Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams, Michael Keaton and Brian d'Arcy James in "Spotlight." (Open Road Films)

“If it takes a village to raise a child, it also takes a village to abuse a child.”

Thus speaks one character in Tom McCarthy’s stirring newspaper drama “Spotlight,” which is both a crepuscular paean to the slowly vanishing age of the metropolitan daily newspaper and a hymn to the virtues of old-school shoe-leather investigative journalism, the kind that gets results and changes lives and cities. In “Spotlight,” it takes a big city to hide the sexual abuse of children for generations; it takes a big-city daily to expose it.

“Spotlight” is named after the specially dedicated investigative reporting unit of The Boston Globe—the oldest of its kind in the United States, founded in 1970—and focuses on its groundbreaking 2001-2003 investigation into widespread sexual abuse of children within the precincts and cloisters of the Massachusetts Catholic Church.

As we learn, the church had on its hands a catastrophe for which it was as deeply culpable as Union Carbide at Bhophal or Exxon with its Valdez oil spill in Alaska—and it behaved as atrociously in its denials, evasions and yearslong serial cover-ups as either of those satanic corporations. Part of the problem was that self-same village mentality: Both the church and the Globe loomed large in the roster of ancient and formidable metropolitan institutions in Boston—City Hall and the Chamber of Commerce being the others—deeply interlinked over decades, wielding different kinds of power in the city, and often in league with one another, for good or ill.

Each is in the citizenry’s lives on a daily—or at least a weekly—basis: the church administering to its flock, either honestly or pervertedly, from Cardinal Bernard Law at the top down to every parish priest in the Boston Diocese; the newspaper meanwhile delivering the news—and an equivalent, parallel sense of community—to its readership, its editor a figure of comparable influence to the cardinal, its delivery boys familiar and ubiquitous pre-dawn figures in any suburb.

But the arrival of a new editor-in-chief, Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), a lone, out-of-town Jew among the native Boston Catholics, upsets the age-old fraternal familiarity between church and paper. Determined “to make this newspaper essential to its readership,” Baron is unencumbered by the kinds of institutional and religious loyalty and folk memory that have hitherto kept the Globe from digging too deeply into rumors long prevalent, in a subterranean way, about abusive priests. When a story about the hands-off treatment by the church of one of them, the notorious long-term rapist and molester Father John Goeghan, threatens to lead upward and outward, Baron puts the reluctant Spotlight team on the story.

Consisting of unit editor Walter “Robby” Robinson (Michael Keaton) and dogged reportorial bloodhounds Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) and Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams)—with the nervous approval of deputy managing editor Ben Bradlee Jr. (John Slattery)—the team resolves not to publish a word until they have followed the story all the way to the top—to Cardinal Law himself (Len Cariou), who soon emerges as a man unwilling to face the vast hidden crisis in his diocese. Indeed, he is a man eager to transfer priests out of parishes where they have offended and into new parishes until they reoffend, as all of them seem to do.

The story is built by degrees, with certain discoveries proving dead ends while others open up whole new and disturbing vistas of evil and corruption. Most of the reporters are themselves Catholics, albeit mostly lapsed or doubtful, but they have all been marinated in the church’s sense of its own righteousness and probity; it is as hard for them to believe or accept what they discover as it is for abused kids to revisit their traumas or for the church to confess its culpability. And their inquiries lead other places as well: into the district attorney’s office (run by a silkily smarmy Billy Crudup), long in league with the church’s cover-ups, and even into private law firms making a tidy profit from the misery of the plaintiffs—their cut of each paltry, nondisclosable, out-of-court $20,000 settlement awarded to abuse victims. Old case files and depositions are sealed by the court and thus unavailable to reporters, the church is oleaginously evasive and threatening (Cardinal Law creepily invokes “meddling outsiders” in his first meeting with the Jewish Baron), and there is a resounding sense among the city’s lay elite that some stones are best left unturned.

The story also reaches deeply into the city’s past: Many of the priests were themselves abused as children, and the church, it turns out, admitted—if only to itself and only in secret—that an old 1985 abuse case threatened the church with “a billion-dollar liability,” and the only recourse was a gigantic cover-up. The tragedy is that the Spotlight team members are almost the last people to learn about the sheer extent of the abuse. As Robinson says, “It’s like everybody but us already knows this story.”What makes “Spotlight” so compelling is its absolute focus on the nuts and bolts of investigative journalism itself. It doesn’t lay great crises of faith or out-of-office melodramatics on its journalist characters, whose lives away from the newsroom are barely outlined. It concentrates on the central values, mechanics and instruments of investigative journalism: following the story wherever it leads; asking the right questions of the right person at the right moment; putting in endless hours in public records offices, newspaper archives and dusty, old registries at law firms. The journalists’ only weapons are Rolodex, shoe leather, filing cabinet, telephone, doorbell and relentless backup sourcing.

What they find horrifies them over and over again. They trawl through the records of the church and find that priests are counseled in-house by church psychiatrists and then, naively or cynically, redeployed in other situations where they will inevitably come into contact with children. Recidivist offenders are housed and ever-so-delicately chided in church-owned community residences until they are fit to rejoin society. (One of these houses is literally around the corner from the home of one of the reporters, who has children of his own—he posts a stay-away warning for them on the fridge). We learn from an informant who has inside knowledge of how priests are treated (Richard Jenkins, in a voice-only cameo) that the church’s celibacy dictates lead inevitably to the infantilization of priests’ sexuality, leaving them “basically 12 years old, in sexual terms,” and that as many as 6 percent of all Boston’s priests have abusive pasts. Most hauntingly of all, as one reporter tells another, “the church thinks in centuries. … Do you?” This enemy has been hiding things from us for fully two millennia.

“Spotlight” also features any number of clever links to other, older newspaper melodramas. Most notably, McCarthy, its director and co-writer, played Scott Templeton, the skeezy, Pulitzer-hungry young city desk hack who singlehandedly depraves and perverts the entire Baltimore Sun in season five of David Simon’s “The Wire”—he’s an absolute cancer on his newsroom. Michael Keaton played the editor in Ron Howard’s so-so big-city-daily drama “The Paper,” in which his chairman was played by Jason Robards in an echo of his role as Ben Bradlee Sr., father of the Slattery character in “Spotlight,” in the granddaddy of investigative reporting movies, “All the President’s Men.” Liev Schreiber arrives fresh from season three of “Ray Donovan,” in which he plays one of three adult Bostonian criminal brothers, all traumatically abused by their childhood priest—whom Schreiber’s character murders in season one. The camera surveying the newsroom from a rolling file trolley is a steal from the San Francisco Chronicle setting of David Fincher’s “Zodiac,” and the imagery of “All the President’s Men” is repeatedly echoed, both in the size of the conspiracy the “Spotlight” team is unpicking and in the old-school reportorial methodology of its characters.

I have not been a particular devotee of McCarthy’s earlier movies as a writer-director. They include “The Station Agent,” “The Visitor” and “Win.” To me, their virtues seem actorly and writerly, not particularly cinematic. This is not a problem in “Spotlight,” however, where the procedural is paramount. The screenplay—co-written with Josh Singer—is as tight as a drum and never oversells, fictionalizes or betrays the real-life story it is telling, and McCarthy has taken the serve-the-screenplay/efface-the-directorial-personality approach often espoused by hands-off maestro Robert Wise.

The result pays a deeply respectful, rightly nostalgic homage to the now-fading role of the big-city daily in our lives, starting at a time, only a decade ago, when the intrusion of the Web into newspaper classified ad sales (here ruefully noted) was just the now quaint-seeming thin end of a wedge that has since ruthlessly extinguished or hobbled countless print newspapers and magazines. (I am writing this one day after the Philadelphia Media Network performed a newsroom massacre, and in the week that Rupert Murdoch purged the editorial staff of his latest acquisition, National Geographic, starting, characteristically, with the fact-checkers.) But it also hails pure investigative reporting as an essential component of truth and democracy.

We will soon realize that we don’t, after all, need newspapers themselves anymore, as presently constituted. But we will always need journalism, and if it goes down with the newspapers, we’re all in terrible trouble.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.