Speaking the Unspoken

Julie Delporte's autobiographical graphic novel wrestles with issues of sexual abuse, fantasies of motherhood, and the creation of art. Drawn and Quarterly

Drawn and Quarterly

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

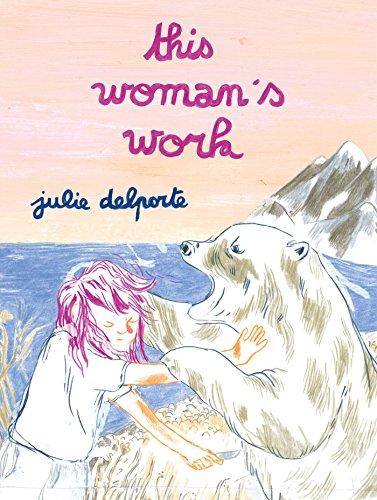

“This Woman’s Work”

A book by Julie Delporte

Julie Delporte’s raw and devastating graphic memoir, “This Woman’s Work,” chronicles the 35-year-old author’s struggle to decipher what befell her as a small child. She often seems to be still swallowed whole by grief.

Delporte was assaulted as a little girl by an older cousin. She grew up in France, the daughter of nonartistic parents, and moved alone to Montreal at 22, where she began writing autobiographically tinged graphic memoirs that chronicled her distress. Her previous works, “Journal,” and “Everywhere Antennas,” have drawn much praise for the evocative colored pencil sketches that seem to float on a larger page of empty white space. The illustrations are roughly drawn, almost childlike at times; her small cursive handwriting seems to disappear before our eyes, and her brief utterings are often cryptic. She allows us to fill in the blanks. She purposely leaves taped-on edits on certain pages showing us the messiness of her process.

In most drawings of herself, Delporte’s eyes are closed tightly as if she can’t look at the world directly. She begins her narrative by quoting Goliarda Sapienza, the Italian novelist who wrote about women unrestrained by conventional notions of femininity: “Words unspoken fester inside us.” We sense Delporte’s goal in “This Woman’s Work” is to finally speak the unspoken words. She is only partially successful.

Delporte recalls her father’s stinging words: “Whenever anything was poorly done, my father would joke, ‘must be a woman’s handiwork.’ “ The drawing that accompanies her father’s hurtful words shows us a young woman that appears to be Delporte. She is sloppily dressed and seen from behind, walking away briskly. Is she running away? Or just dreaming about doing so?

The story travels back and forth in time. We see her in Brussels in 2016, living on her own. There is a man in her life, but we learn nothing about him, nor will we learn about any of the others. Men seem to be a mere backdrop for Delporte. She is wary in their presence. Delporte reveals that she wanted to get pregnant that summer. We see her and her lover sitting up in bed, but there is an aloofness, perhaps hostility, between them. It appears they have just made love. But the atmosphere is suffused with disappointment. She writes of what he did not tell her that night in reference to the child they thought they might create:

“I’ll take care of her

You’ll be able to draw

I’ll change the diapers

I’ll even nurse her.”

She is fearful about marriage and motherhood and how it will infringe on her ability to produce art.

But fantasies of motherhood mock her. There are sketches of mothers holding small children cradled tenderly in their arms. They are often followed by disturbing references to the disastrous fates that befell these mothers. Some died in childbirth; others retreated to the suburbs and the tyranny of domesticity; and still others had children who brought them only distress. We see Delporte conflating motherhood with disaster repeatedly and her sketches seem to grow more vibrant with this assertion. She asks, “How old was I when I started feeling cheated simply by being a girl?”

When she approaches her own history, her eyes close again. We see a drawing of a little girl, about 10, lying in bed with a short dress pulled up, leaving her private parts exposed. Next, we see her leaving the bed and putting on her socks. There is a close up of one eye, stunned and wide open. She writes that she resents how her family whitewashed this event as “kids just being kids.”

She does not say much about her parents or her family, except that “I often look at my family tree and wonder which of these women were raped.”

She seeks solace in reading about women who have been able to live without men. Women who were artists like herself. The life of Tove Jansson, a Finnish artist who invented the “Moomin” comic strip series, captures her imagination. Jansson was a lesbian who lived with her lover for 45 years in a seemingly idyllic union. She never wanted any children, fearing, like Delporte, that they would interfere with her ability to make art. Jansson too lives with a “constant desire to learn how to make things. Beautiful objects, more tangible than a text or drawing.” Jansson’s Moomins were fluffy figures who could protect all children from harm. Delporte was enchanted by one of the Moomin characters named Snufkin, a philosophical vagabond of sorts who fished, played the harmonica, and was able to embrace life in the moment. Delporte wonders if Snufkin was able to be so carefree because he was a boy Moomin.

Delporte is also smitten with Amy Berkowitz’s work and her biting revelations about chronic illness and sexual violence. She studies the paintings of Paula M. Becker, a German painter, the first woman artist to paint nude self-portraits of herself, using a haunting simplicity of form. Becker died at 31 from a postpartum embolism. Delporte scrutinizes the majesty of Louise Bourgeois’ paintings that looked at domesticity, sexuality, and the body’s need to protect itself from outside harm. And she mourns for her peer, Genevieve Castree, who died from pancreatic cancer. Castree’s work as a graphic artist delved into the anxiety women feel about finding a space for themselves in a world that entangles them elsewhere. But these are other woman’s voices; not her own.

Delporte remains flustered and asks “What do men want from me?” She is staring nervously at her silent cellphone, hoping a guy she is attracted to will call. He does not.

She returns to fantasies about worlds without men. She thinks of the beguines, flocks of females who lived in harmony without men centuries ago. Sometimes they drank rum together at night while sharing poetry. Delporte laments that there are no recorded accounts of their intimate lives. Yet men seem necessary to her despite her protestations. She asks herself nervously, “What men would be able to live with a feminist.… What men would I be able to live with?”

Another day she is picking mushrooms with a friend beneath an enormous canopy of trees, and mentions something nonchalant about God and the beauty of the trees. It is only then that we realize she has never spoken about God before, and now seems content to give him only a brief and wary nod.

Delporte’s work is a depiction of unresolved anguish. Her sketches and brief searing captions feel like ambiguous messages sent to us from a distant planet, one filled with primal pain. We feel a kinship with her reverence for female liberation, but truthfully, even this admirable goal crumbles as we witness her joyless life and the absence of laughter. She resists tackling the complexity of human desire. She never reflects a sophisticated understanding of the dramatic tension and wondrousness that sometimes exist between men and women, and the sacrifices required to survive in that realm. Words like negotiation and confrontation would probably terrify her. She sees compromise as a sellout and this blindness paralyzes her. Delporte does not realize that human relationships need not be sacrificed in order to create art. In fact, each arena can and does fuel the other. But she twirls like a butterfly off the page, leaving us with her 10-year-old face lying listlessly on her childhood bed. Her eyes are closed.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.