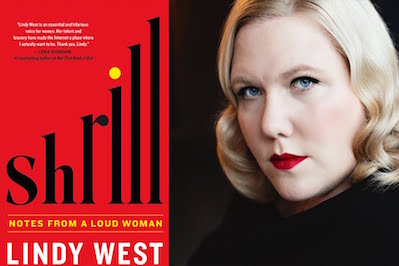

Shrill

With a kind of cultural jujitsu, feminist Lindy West has memorably taken on fat-shaming, rape jokes and men who harass women online under the guise of free speech. The lovely thing is that she's funny about it.

“Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman” A book by Lindy West To see long excerpts from “Shrill” at Google Books, click here.

Lindy West’s new book, “Shrill,” will be pilloried in certain corners for carrying an agenda. The guys who call themselves men’s rights activists, for instance, won’t be giving it good reviews. West, who has written cultural criticism for GQ, Jezebel, the Guardian and other outlets, is a feminist and a fativist (if you’re not familiar with that term, it’s exactly what it sounds like). But beware: Such labels have a way of making the bearer seem narrow and her tone, yes, shrill. West is anything but. She has written a compelling book on behalf of human decency.

In recent years, West has memorably taken on fat-shaming, rape jokes and men who harass women under the guise of internet free speech. The lovely thing is that she’s funny about it. In her book — part memoir, part cultural critique — the Seattle-based writer explains that comedy was her first love. As a kid, her favorite shows were “Saturday Night Live,” “Mr. Show,” “Fawlty Towers” and assorted late-night comedy programs. The sensibility of these shows and years of writing for online outlets like Jezebel appears in West’s irreverence and comedic timing. She writes like you’d imagine she talks, with all caps and emphatic vowel sounds. Reading her is a full-on sensory experience. The loud blonde is in charge, and the rest of us will go as fast as she likes.

West, who is in her 30s, says that for much of her life she was shy, partly by temperament and partly perhaps to make herself seem less big in a culture that prizes delicacy. She writes about how being fat has made her both terribly visible and invisible — she is hard to miss and yet no one really sees her. She is at once despised and unworthy of eye contact.

Strangers hand her brochures for dietary cleanses. Men want to date her but not be seen with her in public. Despite her best efforts over the years, West has found dieting impossible: To shrink to a culturally approved size would require a degree of constant deprivation that “essentially precluded any semblance of joyous, fulfilling human life.” She’s built big, and for years she exercised the only culturally approved option, which was to hate her body.

But disgust at fat bodies, West argues, is not innate. She writes of overcoming her own feelings with a self-crafted aversion therapy that involves looking at naked fat women online. (Really.) She writes of realizing, in her 20s, that her signature weakness — her body — was, in fact, “an opportunity. It was political. It moved the world just by existing.”

Working at the Stranger, an alternative Seattle newspaper, a few years back, she publicly took on a higher-up whose writings on the obesity crisis were, she thought, intended to shame people like her. The resulting piece — “Hello, I Am Fat,” posted alongside a photograph of West — utilized what would become her signature rhetorical jujitsu. With her self-deprecating humor and logistical skill, West turns her vulnerabilities into strengths. She is sharp and funny and likable, which makes her cool, which makes her not how people imagine mouthy feminists to be, even in this Amy Schumer age.

In more recent years, West has dissected the gender war that ensues when male comedians make rape jokes, and analyzed the function of the jokes themselves. In her book, she neatly encapsulates the counterargument to those who say that she’s trying to censor comics (she isn’t), or that comics should be able to say whatever they like (certainly they can) without repercussion (no dice). She explains the comedic principle of never punching down, and how making light of sexual violence typically fails the important test of being funny. And she recounts how her writing on the topic led her to debate comic Jim Norton on a cable TV show, which led to swarms of men threatening her with rape and worse in an online attack campaign — which led to another of West’s epiphanies.

“They’d handed me a gift, I realized. A suffocating deluge of violent misogyny was how American comedy fans reacted to a woman suggesting that comedy might have a misogyny problem.”

West had someone film her reading the worst messages she’d received, and posted it online, prompting a turnaround on Twitter. Cultural jujitsu, again.

Still, the losses that accompany being a woman online are significant, and serve to drive home the courage of West and many others — feminists, critics, sportswriters, gamers. The drumbeat of rape and mutilation threats have shut many a good woman down, which is precisely their point. West writes about the inadequacy of our prevailing wisdoms — that such threats don’t count because they’re made online, that they should simply be ignored, that they’re the price of existing on the internet.

She also writes of other pleasures she has lost: of being unable to watch stand-up comedy anymore because it has been the site of so much hostility, of having to stop listening to an earlier era of “The Howard Stern Show” because the price of all that sharp humor was the debasement of so many of Stern’s female guests.

“In a certain light,” West observes crisply, “feminism is just the long, slow realization that the stuff you love hates you.”

“Shrill” movingly recounts other chapters in West’s life, including an abortion she had at 27, her marriage and the death of her father. But it’s her ability to flip cultural assumptions that fill this reader, at least, with awe.

One of the more stunning moments in this book is West’s account of her confrontation with a cyberbully. In 2013, she was harassed online by a man pretending to be her dead father. She made her hurt public, writing about it in a piece on how women are (mis)treated on the internet.

The perpetrator e-mailed her and apologized. West followed up by interviewing the guy for “This American Life.” That radio piece played like vindication for any citizen of the online world who has ever been anonymously harassed, and demonstrated if that anyone can reach an internet troll, it’s Lindy West. She was sad and angry, but also deeply compassionate, using her humanity as a wedge to elicit his. “You can’t claim to be okay with women and then go online and insult them — seek them out to harm them emotionally,” the man told her, acknowledging his past closet misogyny. “I don’t know what else to say except that I’m sorry,” he added later.

The whole exchange would have been impossible if West hadn’t been willing to engage on the front lines of cultural debate, to absorb the blows and keep coming. That segment, like “Shrill,” showcases her optimism about humans, about our ability to talk things through and be better to one another.

Thank goodness she still believes in us.

Libby Copeland is a former Washington Post staff writer.

©2016, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.