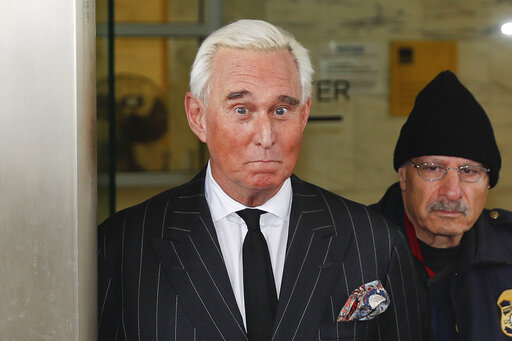

Should ‘Dirty Trickster’ Roger Stone Be Silenced?

Placing a gag order on the GOP consultant, as Robert Mueller has requested, is not only unnecessary, but most likely unconstitutional. The former campaign adviser for President Trump leaves federal court in Washington, D.C. (Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

The former campaign adviser for President Trump leaves federal court in Washington, D.C. (Pablo Martinez Monsivais / AP)

Roger Stone, who has been charged with lying to Congress, obstruction of justice and witness tampering in the ongoing investigation of Russia’s ties to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, will go on trial later this year in Washington, D.C. Any day now, federal District Court Judge Amy Berman Jackson, who is presiding over Stone’s case, will rule on special counsel Robert Mueller’s request that she place a gag order on Stone and his attorneys. Such a move would prohibit Stone and his counsel from making public statements about the case outside of court.

Like many federal judges, Jackson is a former prosecutor, having served as an Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Columbia from 1980-1986. Barack Obama appointed her to the bench in 2011.

Jackson is no stranger to gag orders. In November 2017, she placed gag orders on both Paul Manafort and Richard Gates in the case Mueller filed against them in the nation’s capital.

Although Manafort and Gates did not contest their gag orders (Manafort was subsequently accused of violating the order), Stone has declared he will resist any attempt to issue one in his case.

Last week, the Trump campaign adviser’s lawyers filed a legal brief setting forth their objections to a possible gag order. In a nutshell, the attorneys say that while they, as officers of the court, are personally prepared to comply with Jackson’s ultimate ruling, any order gagging their client would run afoul of the First Amendment.

I am no admirer of Roger Stone. To the contrary, I think he’s among the slimiest of slime-balls for his self-described history as a “dirty trickster” during a decades-long career as a Republican consultant and campaign operative.

I am, however, an admirer and defender of civil liberties. All Americans, including slime-balls, are entitled to the full panoply of liberties enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. In this respect, if in few others, Stone and his attorneys are correct: a gag order on Stone is both unnecessary and would likely be unconstitutional.

As Stone’s lawyers elaborate in their brief, at this stage of the proceedings, gagging Stone would amount to a “prior restraint” (a proactive, before-the-fact prohibition) on free speech. The Supreme Court, they note, has recognized that prior restraints on speech “are the most serious and least tolerable infringements on First Amendment rights.”

In a hearing held on Feb. 1, Judge Jackson recognized Stone’s “legitimate interest in exercising his First Amendment rights. But,” she continued, Stone also “has an interest in exercising his [Sixth Amendment] constitutional right to have a trial and to put the government to its proof. And it’s my responsibility to ensure that he has a fair trial.”

Jackson reserved passing judgment on the issue, pending briefing from Mueller’s office and Stone’s lawyers. The briefs have now been filed.

The tensions between First Amendment free-speech values and Sixth Amendment fair-trial rights make gag orders inherently problematic and controversial.

To understand those tensions, it’s necessary to recall that, historically, gag orders have been imposed both on trial participants—particularly the parties to a case and the lawyers who represent them—and the press. The law, however, has not treated treat both types of orders the same way.

Gag orders on the press have long been disfavored. In the landmark 1976 case of Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, the Supreme Court devised a three-part test to measure the constitutionality of media gag orders. Before gagging the media in its coverage of legal proceedings, a trial judge must ask (a) whether publicity would undermine the prospects for a fair trial before an impartial jury; (b) whether a gag order is the least restrictive means to ensuring a fair trial; and (c) whether a gag order would actually be effective in quelling publicity.

Because it is difficult to meet all three prongs of the Nebraska test, media gag orders are often overturned on appeal and thus, in practice, have become increasingly rare.

As a result, trial judges concerned with potentially explosive reporting about ongoing litigation have resorted with greater frequency to placing gag orders on trial participants. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has yet to rule on whether the Nebraska test applies to trial participants in addition to the media. Some federal appellate and state courts have held that the same test, or something close to it, should apply across the board. Others have treated trial-participant orders more leniently.

In a 2001 analysis, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press charged that “Gag orders on trial participants have become a significant threat to the First Amendment protection for the press.” In the committee’s view, such orders not only curb the vital work of the media, but they also violate the public’s First Amendment right to receive accurate information about what transpires in our court system, which, after all, is supposed to be a public forum.

Were the Nebraska test applied to trial-participant gag orders, as University of California, Berkeley Law School Dean Erwin Chemerinsky has advocated, it’s difficult to see one imposed on Stone passing constitutional muster.

For starters, Stone doesn’t want to curb publicity about his case. He is a media hog and wants to be part of the dialogue. In TV interviews following his indictment, he argued that a gag order would restrict both his ability to work as a political commentator and to raise money from supporters to help pay for his legal defense.

Judge Jackson also has alternatives to gagging Stone to ensure that both he and the prosecution receive fair trials, including conducting extensive questioning of prospective jurors during voir-dire, and issuing stringent admonitions to jurors after they are seated to base their verdict solely on the evidence presented in court.

Most important of all, silencing Stone will in no way limit media coverage of the case. With or without a gag order, the Republican consultant’s trial promises to be the biggest courtroom happening since the prosecution of O.J. Simpson.

This isn’t to say that it’s wise for Stone to speak out about his case. Mueller and his colleagues no doubt will carefully parse any public statements he makes for any and all incriminating inconsistencies. Given Stone’s penchant for hyperbole and outright prevarication, he would be well-advised to keep his mouth shut. Otherwise, he could wind up making Mueller’s job as a prosecutor easier.

But that’s not a decision for me or anyone else to make. In a criminal justice system in which every accused is supposed to be protected by the Constitution and in which everyone is presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, the decision should be Stone’s alone.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.