Ruth Scurr on Paris

This is the Paris you never knew: From the Revolution to the present, two new books deliver a series of astonishing stories, all stranger than fiction, of the lives of the great, the near-great, and the forgotten.From the Revolution to the present, two new books deliver a series of astonishing stories of the great, the near-great, and the forgotten.

This review originally appeared in The TLS, whose website is www.the-tls.co.uk, and is reposted with permission.

In the fifteenth of his “Theses on the Concept of History” (1940), Walter Benjamin noted that “calendars do not measure time as clocks do”. Benjamin, that “peerless Paris pedestrian”, is an inspiration for Eric Hazan’s fascinating book The Invention of Paris: A history in footsteps. In his preface to the new English edition (the book was first published in French in 2002 as L’Invention de Paris), Hazan notes that to spot what has changed in Paris in the last eight years, he would need to have gone away and returned after a long absence. Instead, he has been in Paris almost continuously recently, “and so I see it changing like the wrinkles on a beloved face that one observes every day”.

Hazan was born in Paris in 1936 (his mother was born in Palestine and his Jewish father came from Egypt). He studied medicine, left France in support of the FLN during the Algerian war, and later worked as a volunteer doctor in a refugee camp outside Beirut. In 1998, he founded the radical publishing house La Fabrique. His is a cleverly structured book. Tracing the walls and administrative boundaries that have successively encircled Paris down the centuries, Hazan describes how the city grew beyond them, like a grand and beautiful tree. He defines “Old Paris” as the area within the Boulevard of Louis XIV (the tree-lined avenue the King had built in the 1670s on the circuit of the razed old city walls) and “New Paris” as the area outside. “New Paris” is divided into two concentric rings: first, the ring of the faubourgs (covering the area beyond the Boulevard of Louis XIV up to the hated Wall of the Fermiers-Généraux, which was built to enclose the city for tax purposes in the 1780s); and second, the ring of “the villages of the crown” (covering the area beyond the Wall of the Fermiers-Généraux to the Boulevards des Maréchaux, which were begun in 1920, on the site of the defensive wall Adolphe Thiers had built in the 1840s).

Today you cannot see the line of the Boulevard Louis XIV, little remains of the Wall of the Fermiers-Généraux, and the Boulevards des Maréchaux have been lapped by the alarming Boulevard Périphérique: certainly more motorway than walkway.

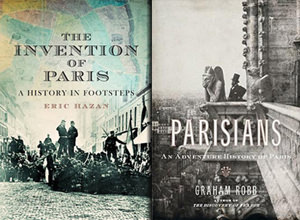

The Invention of Paris: A History Told in Footsteps

By Eric Hazan

Verso, 400 pages

Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris

By Graham Robb

W. W. Norton & Company, 496 pages

At the heart of old Paris, in the Right Bank quartier of Tuileries-Saint-Honoré, Hazan marks the location of the house where Robespierre lived during the Terror, at the end of the rue Saint-Honoré: “the geographical axis of political life” in the Revolution. Within the same quartier lived the abbé Sieyès, Olympe de Gouges and Bertrand Barère. The Jacobin Club, the Convention, and the Committee of Public Safety, all met close by. In 1946, the Place du Marché-Saint-Honoré was renamed the Place Robespierre, “a decision reversed in 1950”, Hazan writes, “when the French bourgeoisie raised its head again”. Hazan’s radical sympathies are in evidence during his alert and erudite walks: in the Bourse quartier he notices the Hôtel de La Vrillière, designed by François Mansart, confiscated during the Revolution and turned into the Imprimerie Nationale. “Robespierre’s speeches were printed in runs of 400,000, and Marat needed three presses in the courtyard to print L’Ami du peuple.” In the Sentier quartier, Hazan commemorates the heyday of the daily press, between the end of the Second Empire and the First World War. Since then, the migration of printing works to the suburbs has left behind “only pale vestiges of this glorious age: the Figaro building on the corner of the Rue du Mail, the Tribune building, the fine caryatids of the building of La France, journal du soir, and the plaque on the Café du Croissant marking another Socialist lieu de mémoire: ‘Jaurès was assassinated here on 31 July 1914’ “.

After his methodical street-by-street tour of the city, old and new, Hazan focuses the second part of his book on “Red Paris”, which is introduced with lines from Baudelaire’s projected epilogue to the 1861 edition of Les Fleurs du Mal: Your metal domes fired by the sun, Your theatre queens with enchanting voices, Your bells, canons, deafening orchestra, Your magic cobbles erected into fortresses, Your little orators with baroque turns of phrase Preaching love, and then your sewers full with blood, Pouring into hell like so many Orinocos.

Hazan presents the nineteenth century as “the heyday of that great symbolic form of Parisian revolution that is the barricade”. At the centre of the Paris Commune of 1871, he describes Louise Michel — Anarchist, teacher and medical worker — reading Baudelaire in a trench while bullets whistled over her head. Fighters on either side of the barricades “called out to one another, insulting each other as under the walls of Troy”. In the century between 1871 and 1968, Hazan argues, “the pacification of political manners — in other words, the continuation of civil war by other means — favoured the return of illusion”. In his view, May 1968 was another revolution that has been wrongly described “by the vague and cowardly term ‘events’ “.

“Red Paris” ends with a warning to those who rejoice to see the city so calm today: “The time of the oppressed is by nature discontinuous”, as Walter Benjamin knew, and not for nothing did participants in the street battles of July 1830 set fire to the clocks on monuments.

The final part of The Invention of Paris consists of two chapters, “Flâneurs” and “The Visual Image”, which overlap with a politically milder but equally fascinating new book by Graham Robb, Parisians: An adventure history of Paris. Hazan takes Jean-Jacques Rousseau for an early flâneur, crossing Paris in his sixties to go botanizing from his flat in the rue Plâtrière. He discusses the place of flânerie in Balzac’s personal and physical relation to Paris, and its role in the construction of the Comédie humaine. But it is in Baudelaire’s thinking and writing that the concept of flânerie is most elaborate: For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to choose to set up house in the heart of the multitude amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world — such are a few of the slightest pleasures of those independent, passionate, impartial natures … the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy.

Robb’s first books were studies of Baudelaire: Baudelaire: Lecteur de Balzac (1988), La Poésie de Baudelaire et la poésie française, 1838-1852, and in 1989 he translated Claude Pichois and Jean Ziegler’s seminal biography of the poet. In the introduction to Parisians, he describes his first week in the city: a schoolboy’s present from his parents that included accommodation in a small hotel, a voucher for a boat ride on the Seine, and a coupon for a free gift to be redeemed at the Galeries Lafayette. Robb took his secondhand copy of the works of Baudelaire with him as a guide and sat deciphering the “Tableaux parisiens” and the chapter on “L’Héroïsme de la vie moderne” in a café near the Tour Saint-Jacques: “Parisian life is bursting with wonderful, poetic subjects: the miraculous envelops us; we breathe it in like the atmosphere, but we do not see it”.Baudelaire’s “Tableaux parisiens” is a sequence of eighteen poems published in the 1861 edition of Les Fleur du Mal. Eight of the poems came from the section Spleen et Idéal in the earlier, prosecuted and reviled edition of 1857. Baudelaire added ten new poems to form his innovative contribution to the tradition of Tableau de Paris, which Louis-Sébastien Mercier had begun in the eighteenth century. So it is not an accident that Robb’s Parisians has eighteen chapters, each individually shaped by “narrative devices and perspectives naturally suggested by a place, a historical moment or a personality”.

Like a true flâneur, he believes that, “Every vision of the city, however private or eccentric, belongs to its history as much as its public ceremonies and monuments”. He sets out to write “a mini-Human Comedy of Paris”, grounded in historical fact, but imaginatively reconfigured “to replicate the convenient mnemonic effect of a long walk, a bus ride or a personal adventure”. This book, like Robb’s The Discovery of France (2007), is a romantic, narrative history of a subtle, eclectic and circuitous kind that defines itself in terms of “courtesy to the past”. In bringing his skills as a literary critic and biographer to bear on the history of France, and now Paris, Robb has revolutionized (in the politest sense of the word) historical writing on the cusp between fiction and non-fiction.

The chapter “Lost” describes Paris at the time of the first French Revolution through the short lapse of time (twenty minutes or so) in which Marie Antoinette, trying to escape from the Tuileries with her family on the night of the Flight to Varennes in 1791, took a wrong turn that made her late arriving at the get-away carriage (which was an unwisely conspicuous outsize berline specially constructed for the occasion). How was it possible that neither the Queen of France nor her bodyguards and guide noticed when they turned right instead of left on leaving the Tuileries and ended up crossing the river on the Pont Royal, instead of arriving at the rendezvous in the Place du Carrousel? Around this “apparently extraordinary but in fact quite normal” occurrence, Robb assembles a wealth of detail about the paucity of Parisian maps and rarity of street signs at the end of the eighteenth century. François Cointeraux’s map of “Paris as it is today” (1798), for example, deliberately omitted all the minor streets, “for otherwise the map would have presented nothing but a veritable chaos”. At the end of this chapter, Robb discusses the guillotine obliquely. The journey of the condemned from the Conciergerie, across the river and up the rue Saint-Honoré was about two miles, and Robb imagines that “Some of them, as they descended from the cart and climbed the wooden steps, knew for the first time in their lives exactly where they were, and how they had got there”. Whether or not this is true, Robb succeeds in capturing the sharpened focus of perception that plausibly descends on those who know they are about to die. Like the unnamed man, standing in front of the Tuileries Palace, “who hearing the noise of the crowd, climbed onto the pedestal of a statue and quite distinctly saw the blade of the guillotine fall, at a distance of almost half a mile”, Robb stands well back from the gore and horror of that time and leaves his readers with a new perspective.

The Invention of Paris: A History Told in Footsteps

By Eric Hazan

Verso, 400 pages

Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris

By Graham Robb

W. W. Norton & Company, 496 pages

The history of photography recurs through Parisians, which includes a reproduction of the first known photographic image of a human being in the open air, taken by Daguerre in 1838 from the rooftop of his studio in the Boulevard du Temple. The chapter “Marville” opens with a reproduction of an 1865 photograph of “the back end of a Paris square” which captures both an advertising board (a collage of contemporary detail) and Baudelaire’s childhood home at No 22 rue Saint-André-des-Arts. Robb quotes the famous lines that might be thought the anthem of literary flâneurs: “… stumbling upon words as on the paving-stones, / Sometimes bumping into lines I’d dreamt of long before”. Photography is also important in the chapter “Madame Zola”. Zola owned at least eight cameras and needed his loyal wife Alexandrine to help him carry them about the Champ de Mars. At the very beginning of the twentieth century, they climbed to the second platform of the Eiffel Tower and he photographed the roofscape, “moving around the platform, until he had a complete panorama of the city, from the industrial quartiers in the east to the avenues and gardens in the west”. The result was a representation of the city “as grandiose and coherent as his great sequence of novels”. But mention of another photograph, of Zola pouring tea for his mistress and their two children in the garden of a rented house near Médan, disrupts the suggestion of order and coherence that his “half-marriage” to Alexandrine provided.

The ordering of the eighteen chapters in Parisians is as considered as the ordering of poems within a volume. Beginning at the Palais-Royal (which, according to Eugène Briffault’s Paris à table, 1846, was the first place the Allied forces entering the city after the Battle of Waterloo wanted to go to), Robb progresses through Paris’s architectural, literary, photographic, social and political history in loosely chronological order, with many digressions and meanderings along the way, until he reaches the Périphérique, which was completed in 1973 under the Presidency of Georges Pompidou (“‘Pom-pi-dou’, like the peeping of a car horn”): Before the Revolution, the tax-wall of the Fermiers-Généraux had raised howls of protest. Surrounded from within, the city had laid siege to itself, and an anonymous wit had penned the memorable line, “Le mur murant Paris rend Paris murmurant”: Parisians were muttering about their immurement, bewailing the wall that walled them in. Now the saying was literally true: Paris was surrounded by a continual murmur, a whispering wall of tyres and tarmac, a caterwauling of combustion engines.

Beyond “le Périph”, is Robb’s eighteenth chapter entitled “Sarko, Bouna and Zyed”: the story of the teenage boys from the banlieue whom the police chased into an electrical power station in October 2005. Two of them died, and as the third lay badly burned in hospital, the banlieue erupted in flames: “From Clichy-sous-Bois, the inferno seemed to be heading for the centre of Paris along the Canal l’Ourcq, through Bondy, Bobigny, Pantin and La Villette”. Robb notes that while the Minister of the Interior, Nicolas Sarkozy, talked of “extreme violence such as is rarely seen in France”, people knew they were witnessing “something that was practically a speciality of Paris”: spontaneous violence, urban insurrection, popular revolt. Robb conjures up a final vision of the city that resonates with Hazan’s: Those unsightly quarters of Paris called the banlieue were proving themselves worthy of the capital. One day, perhaps, like other popular revolts, the riots would be seen as the birth pangs of a new metropolis. Paris had been expanding since the Middle Ages, pouring over the plains and flooding the valleys of the river system, as though it would eventually fill the entire Paris Basin. Each eruption had threatened to destroy the city, but each time, a new Paris had risen from the ashes.

|

Ruth Scurr is an affiliated lecturer and college fellow at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. She is the author of “Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution,” 2006. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.