Right Move, Wrong Reasons: Inside the EMI/Apple Deal

Media analyst, scholar and musician Aram Sinnreich takes a close look at tech giant Apple's joint venture with major recording label EMI to offer music that is free of the restrictions imposed on consumers by "digital rights management." Sounds like music to our ears, and those of the iPod-toting masses, but the author detects a hidden agenda behind the deal.Early this month, Apple and EMI made headlines when the two companies announced that consumers will finally be allowed to buy major-label music in a digital format that permits them to exercise their “fair use” rights over the songs in their libraries.

This may very well be hailed from the vantage point of history as a crucial moment in the evolution of the digital music industry, and of the media industry in general. However, the details of the deal suggest that its implementation will fall short of the companies’ consumer-friendly rhetoric, and that we still have a long way to go before digital music can live up to its promise, both as a business and as an entertainment medium.

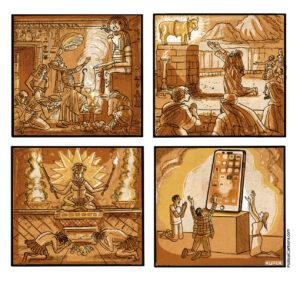

Let’s be clear about this: Digital rights management (DRM), the software padlock that record labels and online retailers typically use to “protect” music files from “piracy,” sucks. If you’ve ever tried to transfer legally purchased songs from your computer to your MP3 player, create backup copies of the albums you bought online or burn a compilation CD to celebrate a loved one’s birthday, you probably know this firsthand. These basic tasks — just a handful of the myriad cool and useful new applications that have convinced tens of millions of Americans to start listening to digital music — are either phenomenally difficult or downright impossible to accomplish when each song is crippled with DRM.

This helps to explain why so many of us have resorted to illegal distribution channels such as peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing networks in recent years, and why most of us continue to shun commercial download services. Unlike legally distributed major-label music files, the MP3s we download from BitTorrent or rip from our CD collections are free of the constraints that DRM imposes: They can be burned, transferred, remixed or reordered as we see fit.

Nearly all of the uses we’ve found for our MP3s, regardless of the files’ legal provenance, fall squarely within our legal rights. Historically, copyright law has balanced the needs of musicians and the music industry to profit from their work against the needs of consumers to enjoy the music they purchase. This means that making backup copies or compilations of our music, selling or trading a song to a third party, and transferring songs from one device to another are all commonly accepted legal fair uses — despite the fact that DRM makes doing them impractical or impossible.

If DRM has been a logistical hassle and an obstacle to fair use rights for consumers, it hasn’t exactly worked out well for the music industry either. The ostensible function of DRM is to “keep honest people honest” by making it impossible for them to redistribute their music via CDs or P2P networks. However, there’s a big logical flaw in this argument. All it takes is a single unlocked copy of a song — easily obtained by ripping a CD or hacking a DRM-encrypted file — to yield millions more via file sharing. In fact, during the past decade there is not a single newly released popular song or album that has not become instantaneously available on P2P networks, regardless of the number of restrictions applied. And, according to Internet measurement company BigChampagne, the number of songs available freely on these networks has continued to rise despite the industry’s use of DRM. Today, the firm estimates, over 1 billion songs are traded each month.

In addition to generating a mountain of bad PR, forcing music fans to choose between crippled songs and illegal distribution channels, and failing to prevent songs from reaching those channels in the first place, the music industry’s embrace of DRM has had another unintentional negative consequence. It has shifted a disproportionate amount of market power down the proverbial value chain, from the record labels to the retailers. More specifically, to Apple.

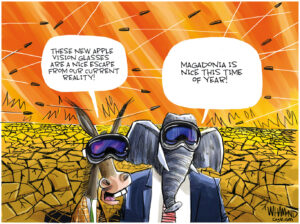

Here’s why. In the last five years, largely through brilliant product design and marketing, Apple has developed a de facto monopoly in the MP3 player market. The iPod is so sexy, so simple to use and so frequently reinvented that it’s generated a kind of self-propelling snowball effect: Everyone’s got one, and everyone wants one. As of this month, only half a decade after it was introduced, more than 100 million have been sold.

The iPod plays MP3s, of course — otherwise, it could never have become so popular. But the only kind of DRM it supports is Apple’s own FairPlay software, used exclusively on songs available from Apple’s iTunes Music Store and integrated exclusively into the company’s iTunes jukebox software. This “walled garden” strategy (imagine CDs bought at BestBuy playing only on CD players purchased at BestBuy) has allowed Apple to artificially extend its dominance from the MP3 player market to the digital music retail market. Today, digital music represents an increasingly vital segment of the faltering music retail sector, and Apple has a virtual monopoly on it. Of the roughly $1 billion spent on digital music by Americans last year, nearly 90 percent went to iTunes.

Despite the rapid growth of the digital music market, Apple’s stranglehold on retail and technology has held it back significantly, and harmed the company’s partners and competitors alike. Because Apple makes all of its music-related profit from selling $350 iPods and merely breaks even selling 99-cent digital songs, it has had little incentive to accede to labels’ demands for higher price points, and no incentive whatsoever to license its DRM to other retailers or MP3 player manufacturers. Consequently, higher-margin, volume-driven digital music subscription providers like Napster and Rhapsody have been unable to sell much music, because their files can’t be played on iPods. In other words, Apple has prevented the market from growing faster because it would rather be the only fish in a medium-sized pond than simply a large fish in a much larger pond.

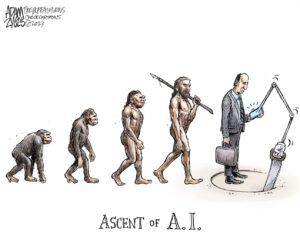

This is why, when Apple CEO Steve Jobs announced in an open letter in February that his company would “embrace” an end to DRM “wholeheartedly” in the interest of “a truly interoperable music marketplace,” it struck some in the industry as disingenuous; Jobs is arguably the individual who has benefited the most from DRM technology.

Why, then, would Jobs advocate and then help carry out the death sentence for a goose that continually lays golden eggs at his feet? The real reason has little to do with interoperability or the rights of music listeners, and everything to do with the next phase of Apple’s digital media strategy.

As successful as the iPod/iTunes cartel has been, the writing has been on the wall for some time. Consumer awareness of and resistance to DRM have continued to grow, and even former RIAA chief Hilary Rosen has come out publicly for an end to the technology. In the meantime, Apple’s current market dominance is based entirely on the continuing success of the iPod device; one false step or market flop and the entire edifice comes down with it. Given the rapid growth of competition from the telecom industry and other sectors, and the accelerating cycles of teen techno-fashion, it seems unlikely that even the sexiest, most brilliantly marketed device can stay on top of the heap forever.

Enter Apple’s next killer app — the iPhone.

First announced in January, only a matter of weeks before Jobs first publicly broached the issue of DRM, the iPhone will combine iPod form and function with wireless phone and data services, ideally forestalling any serious competition from other contenders in the wireless sector. But in order to make the iPhone work, Apple will have to bring down the walls of its garden a few notches. Although AT&T/Cingular is the only partner to have announced support for the device, long-term growth will be contingent on multiple telecom partnerships, and, therefore, technological interoperability. Furthermore, the device represents a step away from Apple’s current strategy of using personal computers as a bridge between the Internet and the portable media player; eventually, it will probably fill itself directly from the Internet using wireless data services, further reducing the strategic and logistical necessity of DRM.

Of course, if Apple were really interested in making things easier for consumers, it would offer EMI’s DRM-free songs in the popular MP3 format, which is supported by every piece of hardware and software currently on the market, and encouraged by EMI. Instead, Apple has opted to distribute its uncrippled tracks in the rival AAC format, which is currently supported only by the iPod and a handful of other MP3 players. While it is true that AAC offers a somewhat better quality-to-file-size ratio than MP3, a real commitment to bringing down the garden walls would privilege true interoperability over such minor technical concerns.

Up to this point, I have largely discussed Apple’s motivations for the announcement; EMI’s are somewhat more straightforward. First of all, Apple made a concession to EMI that it has otherwise resisted over the past five years: raising the price point for songs above the magic 99-cent mark to $1.29. While the financial arrangements of the deal have remained private, music industry insiders agree that EMI has probably raised its wholesale price significantly above the 70 cents or so it gets from DRM-encrypted 99-cent downloads. Another benefit EMI sees from this deal is some sorely needed positive PR. The company has been trying unsuccessfully for years to merge with or to be acquired by another major label, and its bold embrace of new technologies and apparent commitment to consumer satisfaction should appeal to investors and regulators alike.

Of course, EMI’s greatest potential gain is strategic. By doing away with DRM, the company is helping to open up the market to competition, and reducing Apple’s unilateral power over commercial and technological development. Despite the radical nature of this move, however, EMI still has only one foot in the water; the company has announced that, for now, DRM-free distribution will apply only to single-track downloads, and not to digital music subscription services such as Napster and Rhapsody. Until these higher-volume, higher-value services can make their music interoperable with most people’s MP3 players, it’s unlikely that the growth of digital music sales can ever make up for the loss of CD sales.

The end of DRM (in its present incarnation) seems more or less assured at this point. Microsoft has already announced its own deal with EMI to uncripple songs sold through its Zune service, and Apple’s Jobs has announced that he expects more than half of the songs sold by iTunes to be available without DRM by the end of this year. It seems natural to assume that, within 18 months or so, most record labels and most digital music retailers will have gotten on board.

This is great news for both music fans and the music industry; we the consumers can finally exercise our rights to enjoy digital music free of the taint of illegality, and we’ll show our gratitude, at least in part, with our wallets. But many pressing questions remain. When will the garden walls come down completely? When will we be able to spend 10 dollars a month or less to listen to whatever we please, whenever we please, and however we please? When will the recording industry stop blaming consumers for its own strategic missteps and embrace the values it espouses in its press releases? The answers to these questions probably won’t be announced with self-congratulatory fanfare or make the 6 o’clock news. But we’ll be listening closely.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.