Richard Nixon’s Rosebud: Defrocked President Went Wild for Horses

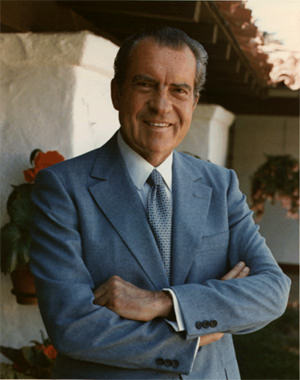

Dec. 15 marks the 40th anniversary of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, a landmark piece of legislation signed into law by Richard Nixon.

Dec. 15 marks the 40th anniversary of the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, a landmark piece of legislation signed into law by Richard Nixon. His association with this bill comes as a surprise to many and so does the fact that the late and oft-maligned president signed a number of critical pieces of environmental legislation — most of which his fellow Republicans are trying to unravel or outright obliterate now. I don’t think widespread acknowledgment of Nixon’s swinging that way would save any of those endangered laws, but his wilderness-minded legacy is generally overshadowed by the Watergate scandal and every other scandal that harks back to it whenever the suffix “–gate” is attached. And that makes it almost impossible to try to broaden the conversation about the big environmental bills that were passed during the Nixon era and now may go the way of the creatures they are protecting.

Nixon’s endorsement of such rules and regulations is often dismissed as being politically advantageous. It was. Yet in recent days, I’ve come to realize that his motivation was fueled by a childhood secret, something that was revealed to an interviewer years after he left office. In the annals of Nixon decoding, this secret stands as the full-on Rosebud of the man who is perhaps the most misunderstood president in history, the very Citizen Kane of the East Coast Xanadu that is the White House.

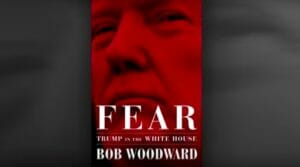

Weirdly, as ever, the beleaguered and awkward commander in chief resurfaced a few weeks ago with the release of some long-held secret Watergate tapes that featured his testimony before a grand jury. Of course the unveiling triggered a brief flurry of coverage, most of which rehashed old conversations about the scandal or lamented the lack of anything that could top what’s already known, which is basically that a shadowy crew called the Plumbers were paid by Richard Nixon and his aides to wage a bizarre surveillance campaign against Democrats, beginning with a burglary at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. — the vast apartment complex where many who toil in the nation’s capital reside. It all culminated in the impeachment and resignation of the president, and a movie starring Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford as the reporters who broke the story, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward — or “Woodstein” as they’re known in some circles. The scandal produced such memorable characters as Deep Throat, the mysterious source who has since been unveiled and died, and G. Gordon Liddy, the spy who was apparently the brains behind the Plumbers’ operation.

With the release of the latest Watergate testimony, there came yet one more round of the usual Nixon coverage. Nixon was a creep, Nixon was a spy, Nixon just didn’t cut it. Well, it’s true — Nixon was a creep in certain ways, or creepy anyway, and he was a spy, having carried out intelligence operations against all manner of American citizens, as well as those inside his own camp who opposed him. And for sure, he didn’t have that one thing that would have rendered all of this irrelevant: charisma.

Yet the flurry of coverage quickly played itself out; Watergate is hardly front-and-center in the national consciousness, and when the story broke, once again the defrocked president had some tough competition in the form of better-looking people. In this case it was a double-header involving Marilyn Monroe, about whom a new movie called “My Week With Marilyn” was on its way to release, and Nixon’s old nemesis, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, whose presence hovered over the entire story due to the stirring of the Marilyn hive, as well as the opening of the new Errol Morris documentary about the mysterious man holding the umbrella near the site of the JFK assassination in the famous Zapruder footage of the incident.

At this point, let me make a strange confession: I wouldn’t say that I have a Nixon obsession, but I’ve been thinking about his legacy for some time. It started more than 10 years ago, when I began writing my book “Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West” and looking into what happened to the wild horses of America. Along the trail, I learned — among other equine-related stories about presidents — that Ulysses S. Grant kept his beloved horses in a stable on the White House grounds and that Richard Nixon had a role in saving the country’s mustangs and burros. In fact, in terms of presidents of the modern era, Nixon was the last friend of the wild horse to occupy the White House — a true cowboy, in effect. Since his time in office, every president has either presided over legislation that modifies the 1971 Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act and/or policy that wages war on our four-legged partner in the making of America.

The 1971 law was the fourth in a series of hard fought legislative victories won by an intrepid Nevada figure named Velma Johnston; she later came to be known as Wild Horse Annie — a joke that backfired and gave her a name that helped make her a hero. As she herself said at the time of her visit to D.C., she had gone from the courthouse — referring to the room in Storey County, Nev., where the first legal battle was waged in the 1950s — to the White House, a long and difficult journey. “We need the tonic of wildness,” Nixon said during the signing ceremony for the bill, invoking Henry David Thoreau — a statement that still ranks as a truly astonishing moment in contemporary American history. Can you picture Nixon making that remark? The more I pondered this scenario, the more I started to question my role in the national loathing of the president who came to be known as Tricky Dick.

It went beyond dislike of his policies and included my participation in a peculiar episode of mob behavior at Yankee Stadium at the height of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s. I happened to have been there during a playoff game, though I don’t remember who the opposing team was. With the Yankees, does it really matter? As always, the ballpark was packed to the rafters and that’s where I was sitting, having purchased tickets with my then-boyfriend at the last minute and taking whatever seating was available.

Suddenly, a chant went up. It wasn’t REGGIE! REGGIE! REGGIE! or anything game related, and I didn’t see any indication of a rally wave breaking out. But very quickly the chant became loud and clear. NIXON SUCKS! NIXON SUCKS! NIXON SUCKS! I joined in, figuring it was yet one more moment of stadium madness that was perhaps responding to an exhortation on the giant fan billboard overlooking the outfield. At the time, it didn’t matter to me; I was down with the Yankees and understood Yankee mania, having had my share of disputes with fans who would show up claiming a box seat that I happened to have at one time or another, claiming it was theirs and producing a ticket stub from some event that happened months earlier — even at other venues — in a desperate attempt to prove it. But as the chant became louder, I quickly realized that something way beyond Yankee fever was playing out. People weren’t just chanting, they were pointing — in the direction of George Steinbrenner’s box. As I looked through my binoculars, I quickly saw that Steinbrenner was entering, along with President Richard Nixon himself. Steinbrenner was somehow embroiled in the Watergate scandal, so seeing them together wasn’t really a surprise. Did the Boss realize that they wouldn’t get a bye, if I may call in a football term, as he entered his kingdom with America’s most reviled figure? Did he care? In any case, on they went as the chant grew to a crescendo, moving toward their seats and taking them. The president managed a wave in spite of 80,000 people yelling that he sucked, and then someone hit a single, I think, and another Yankee rally was under way.

By the time I learned of Nixon’s involvement in wild horse preservation, this kind of behavior on my part — public shouting en masse — had long since fallen away. At some point, I realized that Nixon was a truly tormented man, one who hated rock ’n’ roll and asked radio stations not to play it but happily shook hands with Elvis when he came a knockin’ at the White House gates, a man who spied on fellow citizens making use of the First Amendment when they criticized him, while at the same time defending the one animal that most represents freedom (for the sake of argument, I’m laying down a hierarchy here, with all due respect to brother eagle). And it wasn’t just that he signed the bill and then quoted Thoreau, which would have been more than enough; as I document in my book, he actually went further, much further, and this is the rest of what Nixon said when he signed the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act in 1971: “In the past 70 years, civilization and economics have brought the wild horse to 99 percent extinction. They are a living link with the conquistadors, through the heroic times of the western Indians and pioneers to our own day. … More than that, they merit protection as a matter of ecological right — as anyone knows who has stood awed at the indomitable spirit and sheer energy of a mustang running free.”

Often it’s actors who have the greatest insight into motivation and the true essence of a particular character. The more I thought about the paradox of Nixon, about his own private wars and how they became public, as they always do,in his case, playing out on the world’s stage, the more I wanted to understand him. So I turned to my friend Wendie Malick, a wonderful actress who has spoken so eloquently on behalf of wild horses and other animals on many occasions over the years. What was it in Nixon, I asked, that brought about his defense of wild horses? Clearly there was much more to the story than the sweaty, paranoid guy who hated Eastern elites and didn’t look good on television. “I think he identified with them,” Wendie said. “They weren’t being treated well. They were being rounded up and trapped, sent to the slaughterhouse.” Cast aside, in other words. Not appreciated. And then forgotten. As Nixon himself said in 1952, during his famous Checkers speech, “You won’t have Richard Nixon to kick around anymore.” But actually we do, because that’s what happens whenever anyone mentions his name, and that’s what’s still going on with wild horses.

Which brings me to Richard Nixon’s secret. It has to do with his earliest childhood memories, and as it happens, one of them — to my surprise, and then, ultimately not — is all about a running horse. As the anniversary of the 1971 act drew closer, I found myself again pondering the man whose signature made it official. Armed with Wendie’s insight, I began poring over the Internet for more information about this misunderstood president, hoping to find the thing that led him to identify with wild horses. Why did he feel kicked around? It’s one thing to lose an election and endure an endless media hazing. And who among us could recover from being told by 80,000 people that you suck? Yet his torment seemed so profound, so ancient, that I suspected those experiences must have opened up some unresolved wound. As it turned out, that’s exactly what happened.

And that’s how I came across the Rosebud of this president’s story. Trekking through the Internet, I discovered a series of interviews that he did with reporter Frank Gannon. He talks about his boyhood in Yorba Linda and later Whittier, and recounts loving memories of his parents, like the one in which his mother goes outside to make pie filling, whipping the fresh California air into it to add that special something. But there’s another one, the one that seems to explain a lot, everything perhaps, if one is predisposed to look for that one thing, and even if not, here it is: In this one, he’s a toddler, riding with his mother and sister in a horse-drawn buggy. The buggy rounds a corner and there is a jolt; he is thrown from the vehicle as it continues on, hitting his head as he falls. The horse runs away with the buggy, and young Richard races after it, to no avail. And there he is, dizzy perhaps, stunned maybe, possibly bleeding but determined nonetheless — left in the streets by a runaway horse, an animal that is running faster and faster, trying to break free, vanishing in a trail of dust. And on runs the future president, into his life, the world, the White House, ranting about people who oppose him, compiling an enemies list, making war with Vietnam, peace with China, awed by the sight of a horse running free, forever left behind.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.