Richard Flacks on Pete Seeger

Now 90 years old, America's exemplary troubadour continues his lifelong project to agitate and organize through song, fulfilling his father's dictum that "Music, as any art, is not an end in itself, but is a means for achieving larger ends."At 90, America's premier troubadour continues his lifelong project to organize and agitate through song.

Pete Seeger turned 90 on May 3, providing the occasion for a huge Madison Square Garden celebratory concert, featuring a wide array of popular musicians singing his songs and honoring his influence. In the two years prior to this event, Seeger had gotten more mainstream attention than he’d received in his previous 70 years of performing. Bruce Springsteen recorded several CDs called “The Seeger Sessions” and simultaneously went on an international tour featuring material drawn from Seeger’s folksong repertory. There was a documentary film bio, released on public TV and theatrically, called “Pete Seeger: The Power of Song.” There’s an ongoing campaign to get him nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

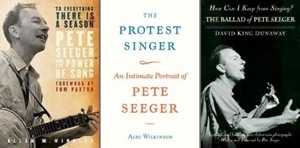

A long adulatory essay on Seeger appeared in The New Yorker and an extended version with the same main title — “The Protest Singer” — is now out as one of three recently published biographies. In addition to the book by Alec Wilkinson, there is a biographical narrative by historian Allan M. Winkler, “To Everything There Is a Season,” and a major updating of David King Dunaway’s “official” biography, “How Can I Keep From Singing,” originally published in 1981.

“To Everything There is a Season”: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song

By Allan M. Winkler

Oxford University Press, 256 pages

The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait of Pete Seeger

By Alec Wilkinson

Knopf, 176 pages

How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger

By David King Dunaway

Villard, 544 pages

The attention Pete Seeger is now getting is certainly deserved, given his influence on American music and the nature of his life story. Yet, one feature of that story is that he is one of the least well-known famous persons in America. I use protest music a lot in my teaching about social movements; over the years, I’ve found that fewer than 5 percent of my students at UC Santa Barbara can identify Seeger (and this is probably a higher proportion than one would find in a sample of the wider public). Of course, the attention he’s gotten in recent years has undoubtedly enabled many more to identify him, but he remains paradoxically shadowy, given his importance.

Yet this paradox goes to the heart of what his life has been about.

One obvious reason for Seeger’s marginalization has been his lifelong commitment to the left. His father, the noted composer and musicologist Charles Seeger, was an important leader of the cultural front fostered by the Communist Party during the 1930s. Charles Seeger helped form a composers’ collective (whose membership included Marc Blitzstein, Aaron Copland and other young radical musicians) seeking to create a new music for revolutionary workers, and eventually working to preserve and reinvigorate folk and vernacular music as an alternative to commodified mass culture. His son Pete grew up immersed in the left, joined the Young Communist League during his brief time at Harvard, and was a Communist Party member (according to his biographers) during most of the 1940s. Although he stopped being a formal member of the party in the late ’40s, he was one of the star cultural figures of the communist-oriented left for many years after that. Teenagers like me and my wife (who both had been “Red diaper” babies) were proud that Pete Seeger was “ours”; there he was at benefits, and hootenannies, summer camps and rallies that defined much of our cultural lives during the ’50s when kids of our background felt pretty isolated from the political and cultural mainstream. Seeger’s allegiances made him the prototype of the blacklisted entertainer, and it was the blacklist which excluded him from TV and blanked him out of the awareness of mainstream America.

But that exclusion was not a tragedy for Pete’s life project. On the contrary, it compelled him to fulfill that project rather than succumb to temptations to modify it that might have come from more conventional commercial success.

Alec Wilkinson’s portrait of Seeger defines him as the epitome of the rugged individualist. We see him in very old age, living in a house he has built on the banks of New York state’s Hudson River. He, his wife Toshi and their small children moved there in the ’40s, and their lives for a time were indeed rugged—without electricity and running water for a while, chopping wood, growing food in a clearing in the forest. Of course, they added modern amenities, but they remained close to the land. Near the end of the book, we see Seeger and members of his clan collecting sap and making maple syrup. Wilkinson appreciates the seeming contradiction that this man, long reviled as a communist, has tried to live the American ideal of the self-made, self-sufficient man.

But Seeger was, in fact, a Communist, and continues to describe himself as a “communist with a small c.” His biographers suggest that when he was a party member, he was sometimes at odds with party discipline. In the ’30s, many CPers from comfortable backgrounds felt the need to demonstrate their revolutionary bona fides by slavish conformity to party lines and party demands. Seeger is described, by Dunaway, as restless with such demands, avoiding boring meetings, alienated by abstract theorizing. Indeed, his dedication to the promotion of folk music was not particularly appreciated by party cultural commissars. But alongside these deviations, he has had to live down the fact that the Almanac Singers, which he helped to found, began in the aftermath of the Hitler-Stalin Pact by recording a group of anti-war songs condemning the start of conscription and FDR’s military buildup. As soon as the Soviet Union was attacked by Hitler, the American Communist Party became a leading advocate of war against the Nazis; the Almanacs put out an album supporting the war effort, and their producer pulled the earlier “pacifist” album from the market. It’s a tale often used to demonstrate that the CPUSA was Stalin’s tool, and how its members were unable to think and act in principled ways. There are some who still can’t forgive Seeger for this episode.

|

To see long excerpts from “To Everything There Is a Season,” click here. |

|

To see long excerpts from “The Protest Singer,” click here. |

|

To see long excerpts from “How Can I Keep From Singing,” click here. |

But Pete Seeger was raised by his father to live a principled life. You can get a flavor of Charles Seeger’s moral perspective by looking at his list of “The Purposes of Music” printed as an appendix to Wilkinson’s book. “Music, as any art, is not an end in itself, but is a means for achieving larger ends. … ” These principles emphasize that music as group activity is more important than individual accomplishment, that “musical culture” of a nation depends on the people’s participation in it rather than on the virtuosity of a few, that “vernacular” music is the foundation from which all other kinds of music derive, that music should “aid in the welding of the people into more independent, capable, and democratic action.” We can read in these lines the foundation for Pete Seeger’s 70 years as an artist and political being. They are a primary source for the life project he began to formulate and implement when he was in his early 20s.I use the word project instead of career because Seeger himself resisted talking about his “career.” The word suggests that one is orienting one’s life toward personal success, climbing a ladder of accomplishment and fame. Seeger from the outset instead set out to channel his ambition toward social and cultural change and, more than most politically minded performers, to exorcise his strivings for personal recognition. The Almanacs in the early ’40s performed anonymously (and Seeger often used an assumed name in those years), emulating various European artistic collectives of that time. A number of politically committed young musicians were part of the Almanacs collective, but Seeger was the most disciplined — focused on enabling the group to stay together and achieve its shared purpose—which was to create new songs, rooted in vernacular music with lyrics that might mobilize political action.

The Almanacs’ most lasting songs were those, like Woody Guthrie’s “Union Maid,” that became anthems of the CIO organizing campaigns, or that spurred anti-Nazi sentiment to support the war effort (“The Sinking of the Reuben James”). Their performances were deliberately unpolished (Guthrie said that they “rehearsed on stage”). In the entertainment world, there was something new and attractively fresh about such public spontaneity, and about the fusion of folk music and contemporary urban topics. The middle-class Almanacs, especially Seeger, undoubtedly thought that their unprofessional style (they wore blue jeans or overalls) would help them forge connections to the working-class audiences they hoped to reach. That assumption has often been mocked; workers were much more likely to want the polished performances of Tommy Dorsey, Bing Crosby or the Andrew Sisters. But this criticism misses the deeper aims of Seeger’s project. It was not popularity or acceptance that he was trying to gain, but the making of space for a popular music that would be created not for the commercial market but for sustaining the “democratic action” envisioned by his father.

“To Everything There is a Season”: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song

By Allan M. Winkler

Oxford University Press, 256 pages

The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait of Pete Seeger

By Alec Wilkinson

Knopf, 176 pages

How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger

By David King Dunaway

Villard, 544 pages

The Almanacs’ collective didn’t last long, in part because several members, including Seeger and Guthrie, entered military service. While in uniform, Seeger continued his project — recording songs of the Spanish Civil War and a number of other topical songs (accompanied by other emerging folksingers such as Burl Ives, Josh White and Sonny Terry). He served in the Philippines as an entertainer for wounded GIs, learning quite a bit about how music can work to build collective morale. By war’s end, he was certain that making politically relevant music was his life’s work.

After the war, Seeger’s energies turned in a surprising direction—toward organizational entrepreneurship rather than merely performing. He sparked the formation of a national network of left-wing music makers (artists, songwriters, presenters, etc), People’s Artists (later called People’s Songs), to serve as a booking agency, a publisher of song-filled newsletters and books, and a support framework for advancing a popular music relevant to political action. In the immediate postwar period, leftists hoped that the dynamism of the ’30s labor movement would continue and that the social democratic logic of the New Deal would be followed by the post-FDR government. Seeger imagined that his people’s music network would be wedded to the unions and leftward social movements, but a profound split in the union movement and the left on the “communist” issue, in the context of the new Cold War, dashed such optimism. The People’s Songs project provided a soundtrack for the third-party Henry Wallace campaign in 1948, but the utter failure of that candidacy and the increasing tempo of the Red Scare thoroughly marginalized the network Seeger had worked so hard to build.

Still, Seeger’s penchant for organizational entrepreneurship was an important dimension of his work that deserves more attention than any of these biographies provide. He has continued to be an organizer since those postwar years. Major successes: the song magazines Sing Out! and Broadside, which published and publicized the politically conscious new songwriting of the ’60s; the Newport Folk Festivals in the late ’50s and ’60s, which brought together a new generation of troubadours with a vast array of traditional performers; a book (first edition mimeographed), “How to play the 5 string banjo,” which taught tens of thousands to play this largely forgotten instrument; the formation of the Freedom Singers by SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee], which toured to raise awareness and money for the Southern struggle (with Toshi as their agent); the Clearwater Sloop, which involved the construction of a large sailing vessel that sparked the movement to clean up the Hudson River and became the center of an ongoing environmental education program. None of these efforts were single-handedly created by Seeger, of course. Indeed, his biographers suggest that he was not exactly a detail person. Toshi Seeger, Pete’s spouse of 67 years, early took on many of the managerial tasks his work required (while managing their household of three children in their log cabin). But he seems always to have had the ability to make the impossible seem plausible and thereby inspire and goad others to help fulfill various of his organizational visions. It’s a rare thing for an artist to be so preoccupied with the mundane tasks of concrete institution building. But he saw, from the start, that artistic efforts per se would not be enough to fulfill the overall project; cultural change is inextricably bound up with social organization.

Seeger’s passion for building alternative institutions was rooted in the cultural left’s longstanding ambivalence about the mainstream culture industry. Those like Charles Seeger and Alan Lomax who in the ’30s wanted to create a popular music rooted in American folk traditions thought that by so doing they would foster alternatives to a mass culture dominated by commercial media. Woody Guthrie frequently expressed disdain for commercial music, and his legend, dramatized in the fictionalized bio film “Bound for Glory,” celebrated his deliberate refusal to accept radio network contracts and nightclub dates. The Almanacs and the postwar People’s Artists thought they could create a noncorporate, social-movement-based apparatus to reach popular audiences, and those hopes were in some ways fulfilled (by a plethora of record labels, community radio stations and the like). On the other hand, the Almanacs, from the beginning, were not averse to commercial opportunity; they and Guthrie did land spots on network radio and in nightclubs. Yet each time such breakthroughs happened, press uproars about their commie politics soon followed, and such bookings declined.Seeger’s most promising mainstream venture was the effort by the Almanacs’ successor group, the Weavers, to work commercial venues. The quartet was born out of the People’s Artists/Henry Wallace cultural left, but was discovered and signed by Gordon Jenkins of Decca Records (one of the largest record labels of the ’40s and ’50s). Jenkins produced a series of Weavers hits (several of these among the biggest-selling singles of the era), and the group was booked into many of the leading clubs and concert venues. The Weavers themselves were uncomfortable with their handlers’ demands that they steer clear of the causes and organizations they had been accustomed to working for, but it wasn’t long before right-wing entrepreneurs of the emerging Red hunt went after them, largely based on Seeger’s long association with “communist” politics. Some two years after they had burst on the scene, the Weavers’ big-time commercial-recording and live-performance career was over.

Seeger may have been disappointed that the Weavers’ successful popularization of folk music was so quickly aborted, but, with Toshi Seeger’s managerial efforts, he quickly embarked on a perpetual tour of America’s college campuses, summer camps and auditoriums, where he honed a solo performance style and repertory that defined who he was as a musician, and in the process brought into being a ragtag army of young fans. He was reviving for urban audiences not only the musical roots of the country but the ancient role of the troubadour, bringing the news through song.

“To Everything There is a Season”: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song

By Allan M. Winkler

Oxford University Press, 256 pages

The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait of Pete Seeger

By Alec Wilkinson

Knopf, 176 pages

How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger

By David King Dunaway

Villard, 544 pages

Seeger’s commitment to his project was embodied in a particular performance style. The key for him was not the display of his own talent and skill, or to thrill or entice an audience. It was instead to bring songs to people so that they could make them their own. Every Seeger performance was centered on group singing. Simply getting a mass audience to join in requires skill, but he aimed further– to teach new songs, and to foster singing in harmony. He particularly relished teaching South African songs, in their original language, that involved two or three competing melodic lines (most famously “Wimoweh”).

Seeger has not to my knowledge laid out a full-fledged theory to explain his emphasis on mass singing. Such a theory, however, is implicit in his performances: There is an empowering effect in the very sound of a singing assembly; there is a persuasive effect that can come when audience members sing lyrics expressing a political perspective or commitment; there is a sense of mutual validation when people in a crowd sing together in an attitude of resistance. And once you sing a song there is a good chance that you will be able to reproduce it by and for yourself. By working as a song leader and teacher, Pete Seeger was achieving his father’s wish for a mode of musical performance that had an ability to “aid in the welding of the people into more independent, capable, and democratic action.”

The blacklisting of Pete Seeger by network TV lasted at least 15 years. Still, his cultural impact steadily increased during that time. The Weavers reunited in a historic Carnegie Hall Christmas season concert in 1955 and thereby defied the blacklist; the recording of this event on the upstart Vanguard label hit the charts, and the group continued to tour and record for several more years (although Seeger separated from it). Seeger drew ever larger concert crowds, including many of the young who heard him first at summer camps or on college campuses. He made, in that period, dozens of albums for Folkways.

Meanwhile, a pop-centered folk song revival became commercially huge. Weavers imitators, led by the Kingston Trio and later Peter, Paul and Mary, sold millions of records. Seeger and the Weavers had shown that folk music could sell, but the resulting commodification inevitably cheapened, denatured and contradicted Seeger’s project. His support of the Newport Folk Festivals helped provide alternative, more authentic access to rooted music and performers. By the early ’60s, a musical rebellion against pop folk was in the works as a band of young troubadours, consciously following in Woody and Pete’s footsteps, started singing. Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, Odetta and many others performed in newly started folk clubs, recorded on upstart labels, appeared at civil rights and ban-the-bomb rallies, and dominated the college tours. Network TV shows featured many of these troubadours alongside the slick bands—but because Seeger was deliberately excluded from these shows, many of the young troubadours boycotted them (even though he personally encouraged some of them to seize the opportunity to get exposure).

The folk music revival was a political as well as cultural phenomenon. The festivals, concerts and clubs where folk fans congregated were among the prime social spaces for shaping awareness and engagement with the Southern civil rights movement and the new left. The early ’60s student activists saw Dylan, Ochs, Baez et al. as “ours” (much as Red diaper babies in the early ’50s claimed Seeger).

Pete Seeger’s belief in the power of song derived in large part from history—the fact that a number of great social movements were fueled by music. There is a tradition of labor song in America, dating from the 19th century, and a number of songs from that tradition continue to this day to help define the identities of labor organizers and raise spirits on the picket line. The Almanacs and People’s Songs were experiments designed to make the U.S. labor movement of the ’30s and ’40s a singing movement—but the results were mixed. Seeger’s dream of a singing mass movement was much more fully realized in the civil rights struggle of the ’60s. Music of course has been a central feature of African-American culture from its very origins. In the early ’60s, as marchers gathered in churches to prepare to challenge segregation with their very bodies, traditional songs and song styles used in these churches were turned into hymns of solidarity and shared risk-taking (with lyrics adapted for the occasion). Pete Seeger contributed to the development of this freedom singing; it was he who had first made “We Shall Overcome” known to civil rights activists in the 1950s, and his concerts in the early ’60s taught the new freedom songs to mass audiences in the North. Seeger encouraged Bernice Reagon to found the Freedom Singers quartet, modeled on the Almanacs, and he and Toshi managed the group’s touring across the country to raise support for SNCC. The music of the Southern movement was an important factor in forging a moral identification with it among Northern students—an identification that led to a flood of volunteers to Southern organizing campaigns and manifold support efforts. In that period, Seeger’s project was finding its fulfillment in his work on stage and as an organizer. You can get a feel for that moment by listening to a recording of his June 8, 1963, concert in Carnegie Hall, available on the Columbia label under the title “We Shall Overcome.” My wife and I were there, and remember it vividly as an experience in which those present were transformed from an audience into a community of active participants in history.

“To Everything There is a Season”: Pete Seeger and the Power of Song

By Allan M. Winkler

Oxford University Press, 256 pages

The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait of Pete Seeger

By Alec Wilkinson

Knopf, 176 pages

How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger

By David King Dunaway

Villard, 544 pages

A few weeks after that concert, Seeger and his family embarked on a world tour, taking nearly a year of travel through Asia, Africa and Eastern and Western Europe. In some of those places, he was able to reach the mass audience denied him in the United States: singing on radio in India to an audience nearly the size of the American population, according to Dunaway; teaching “We Shall Overcome” to people across the planet (which helps account for the fact that it soon became the universal freedom anthem).

If Seeger is often portrayed as a victim of blacklist and censorship, it is clear that his long marginalization from the mainstream was necessary for the fulfillment of his project. When he refused to discuss his political allegiances before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1955 (basing his noncooperation on his First Amendment rights rather than on the Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate oneself), Seeger’s stance took courage: It led the committee to charge him with 10 counts of contempt of Congress, each punishable by a year in jail. Trial and appeal of these charges took some seven years, and Seeger’s blacklisting was reinforced by the legal cloud he was under during that period. In the end, a federal court of appeal overturned his conviction. It was in many ways a costly time for the Seegers, yet as a result he came, says Wilkinson, to “typify the principles of all the brave people he sang about.”

In our time, in a number of countries, troubadours have become icons of resistance. Joe Hill, the Wobbly bard whose funeral after his execution for a murder conviction was attended by thousands, was one of the sources for the Almanacs. Woody Guthrie’s legendary stature in American culture derives in part from Seeger’s efforts to make him known. And then, in the ’60s and ’70s, iconic troubadours were born all over the place: Bob Marley in Jamaica, Victor Jara in Chile, Vladimir Vysotsky in the Soviet Union, Wolf Biermann in East Germany, Cui Jian in China, Miriam Makeba in South Africa. Some of these, like Jara, explicitly used Seeger and Guthrie as models. All were able to achieve stature and profound popular affection despite, and because of, persecution, censorship, martyrdom.

The honors showered on Seeger in recent years include the Medal of Freedom and the Kennedy Center Award. A cynic might say that in America, political troublemakers are marginalized and suppressed, but when they are safely old or dead they are canonized. That’s how we periodically persuade ourselves that we really are a free country. But Seeger’s actual story as told in these books is more complex and more instructive. Wilkinson’s essay stresses Seeger as the epitome of America’s highest values: Beneath his one-time Communist Party affiliations, he was always more like Thoreau—a thoroughly principled individualist, determined to show that each of us could make his or her own life. Winkler emphasizes Seeger’s historical importance in relation to all of the major social movements of his time (the book includes a handy CD compilation of Seeger performances). Dunaway’s updated biography is far more detailed than the others, based on extensive interviews with Seeger and associates and extensive use of his papers. Dunaway gives us a close-up understanding of Seeger’s life choices in their political context. The book details the number of occasions when he entertained serious doubts about his project or his own capacities, doubts familiar to any political activist—the rising frustration when periods of mass action ebb, the sense of obsolescence that comes from personal aging and historical rupture.

We imagine Pete Seeger, at 90, feeling enormous personal fulfillment. How rewarding to get to sing Woody Guthrie’s radical verses to “This Land Is Your Land” at the inauguration concert for our first black president, side by side with one of the biggest stars of popular music! But we can also hear him saying: “Yes, but will the human race survive the 21st century? There’s a 50/50 chance. We’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Richard Flacks is professor of sociology emeritus at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he has taught since 1969. He is the author of “Making History: The American Left and the American Mind,” published by Columbia University Press. His weekly radio show, “Culture of Protest,” can be heard from 6 to 7 p.m. PST at www.kcsb.org.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.