‘Reversing Roe’ Offers an Intense Look at How Abortion Became Politicized

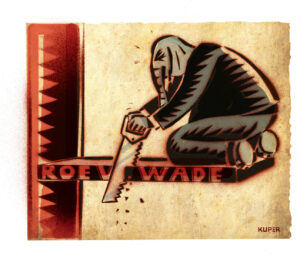

With a timely perspective and candid interviews with figures on both sides of the debate, Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg’s new documentary explores the transformation of a medical procedure into a wedge issue. An image from "Reversing Roe." (Netflix via Youtube)

An image from "Reversing Roe." (Netflix via Youtube)

“We want to end abortion, and we’re going to do it through continuous legislation. We’re going to go back again and again until we win,” Operation Rescue President Troy Newman says at the beginning of the intense, heartbreaking and utterly necessary new documentary, “Reversing Roe.” He stares directly at the camera, his eyes gleaming as he talks of the prospects of restricting women’s rights.

Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg’s “Reversing Roe” is not a history of abortion itself, or a meditation on the morality of the procedure or the people who fight for and against it. Instead, it reveals, through interviews with doctors, lawyers, lawmakers and activists, the story of how a medical procedure became politicized.

That story is not as linear or neat as those of us born after Roe v. Wade might like to believe, and the documentary’s first surprise is how religious figures and Republicans were once in favor of abortion, particularly before it was legal. They included the Rev. Tom Davis, a former college chaplain at Skidmore College (then a women’s college), who unexpectedly found himself counseling countless women through pregnancies they wanted to end but couldn’t tell their parents about. “I learned I wasn’t just a chaplain,” he says, “I learned I was an abortion counselor,” part of a network called the Clergy Consultation Service on Problem Pregnancy. The first legal abortion clinic in America was opened by Protestant clergy in New York City (the Catholic Church was vehemently opposed).

Venerated Republican figures also were once in favor. In 1968, Ronald Reagan, no champion of women’s rights himself, signed a bill allowing abortions under certain circumstances when he was governor of California. Republicans thought outlawing abortion was a form of the government interfering with individual liberty.

Stern and Sundberg smartly allow players on both sides of the abortion debate to simply speak for themselves.

The approach shows viewers how the Republican Party was taken over by evangelicals opposed to abortion and how anti-abortion activists have changed their tactics over time, from protesting (and occasionally bombing) individual clinics, to the less messy but more insidious work of chipping away at abortion rights state by state through legislation to set the course for a national ban.

We hear from Dr. Colleen McNicholas, an OB-GYN based in St. Louis who travels to perform abortions in four states, including the clinic in Kansas where Dr. George Tiller was assassinated in 2009, and Dr. Curtis Boyd, who after decades of performing abortions has now dedicated his life to teaching other doctors how to perform the procedure.

On the other side are pro-life advocates like Newman and John Seago of Texas Right to Life, who explains with all the confidence of a straight-A student why “sonogram technology is one of the best friends of the pro-life movement” and how his organization developed bills requiring that abortion clinics show a sonogram to each woman in an attempt to change their minds.

Stern and Sundberg may themselves have a pro-choice bent, but they give equal time and attention to pro-life activists, who are remarkably candid in explaining their strategies and tactics. On the day of the film’s release, I spoke to the filmmakers about why they made their film, how they chose their subjects and what they hope audiences learn. (This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Ilana Novick: Why did you want to make this film now?

Ricki Stern: We’re interested in looking at how abortion has become such a political wedge issue and so partisan that we had elected a president who very openly said that he would elect pro-life justices, and that they’d be faced with Roe v. Wade and they would overturn it.

We really wanted to ask the question, how have we gotten here? And we wanted to understand those who are passionate on both sides: Those who have strong convictions and have a strategy, in the sense of the pro-life community, strategy to overturn something that they feel passionately about, and, in the pro-choice community, trying to preserve what has been a legal right that has been chipped away at and eroded over many, many years. In the end, I don’t know that it was equal time [that] was as much the driving force, as it was just to say, “We want to understand and be open and we’d love to hear from both sides of this very divisive issue.”

IN: Was there a catalyzing event in the news that inspired you?

Annie Sundberg: When we first started the film, there was a big story that came out in April of 2017 in The New York Times that only seven states in the U.S. had an abortion provider, seven. Kentucky was really on fire because the governor had basically declared war on the last clinic standing, and everybody was wondering, it’s blatantly unconstitutional, because you were completely reducing access within the state and there would be immediate challenges. But, it was a pretty gutsy move to have a governor who was willing to go there and shut down that clinic. It would all of a sudden be the only state in the nation with no abortion clinic.

IN: How did you find your subjects?

RS: We cast this broad net, and we went to the March For Life, we met Jeanne Mancini, we met many people who organized that event, people who were there, we knew that the National Right to Life Committee in D.C. was an important place to stop at and talk to and get their perspective, because they’re in every state. Within the states, we really wanted to understand some of the pro-life perspectives.

We spend time with John Seago, who runs Texas Right to Life. We were really interested in the political strategy of the right-to-life movement. He was very open and honest in talking about the power they wield within Texas, and the relationship with politicians and certain things that the politicians … they have to claim to be pro-life, even if you’re going to be a chief financial officer in the state of Texas.

Troy Newman and Operation Rescue were very open to allowing us to come in and understand their history and their strategy of really closing clinics. They went after a very hands-on, boots-on-ground, closing down clinics [approach]. It’s shifted a little bit now, they’re working with policy and [politicians].

IN: The film’s participants were remarkably candid about both their views on Roe v. Wade and the strategies they use to defend or defeat it. How did you get your subjects to open up to you?

RS: We really try to be open and to allow characters’ voices to come through, to let people tell their stories, to really try to understand what drives people, what motivates people. And as much as possible, and hopefully we’ve succeeded, not editorializing.

Then, [it was] having conversations on the phone before we went in to these cameras, gaining trust within the community. … I think the pro-choice community definitely is [more] cautious, and individuals are cautious, certain clinics are cautious. They feel, as you saw with Planned Parenthood, that they have been exposed, and anything can be used, that it seems, I shouldn’t say anything, but if they’re not careful, things can be used and misrepresented.

IN: Did anything happen either as part of the filming or in the news along the way that surprised you or that made you have to rethink how you were going to make or structure the film?

AS: You could barely keep up with what happens with abortion regulations in these states. It’s almost like, depending on the legislative cycle, bills are getting passed, sometimes bills are buried, abortion bills are buried in other tax bills. It’s not always clear as things are happening. So again, it was really important for us to just land in a few states, Kentucky, Missouri and Texas, and say, “OK, each of these states represents something different that is happening for abortion providers and pro-life activists on the ground. So, we will use these as almost symbols of a broader picture.”

Then of course, when we were finishing the film and we were locked and we were basically about to hand it in, [U.S. Supreme Court] Justice [Anthony] Kennedy retired, and that required us to open up the film again and at least try to make it as contemporary and up to date as possible.

IN: Do you see your film as a form of political intervention?

AS: I don’t know that I would use the term political intervention. I do think that we very much wanted to have a film that felt that it could be both timely and timeless. I think that when we started this film, it was interesting at the top of 2017, when we were at the Women’s March and the March For Life, there were many, many, many young women who were fired up on both sides of the issue. Not a single one of them had ever lived in a world without access to full care and access to legal abortion. It just feels that the political nature of the Supreme Court, and the potential for a fifth vote that could really make things much more restricted for women, it was really the right time.

“Reversing Roe” is now out on Netflix, and in limited theatrical release. Watch the trailer below.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.