Reimagine and Rebuild Our Broken Democracy — in Time for the Nation’s 250th Anniversary

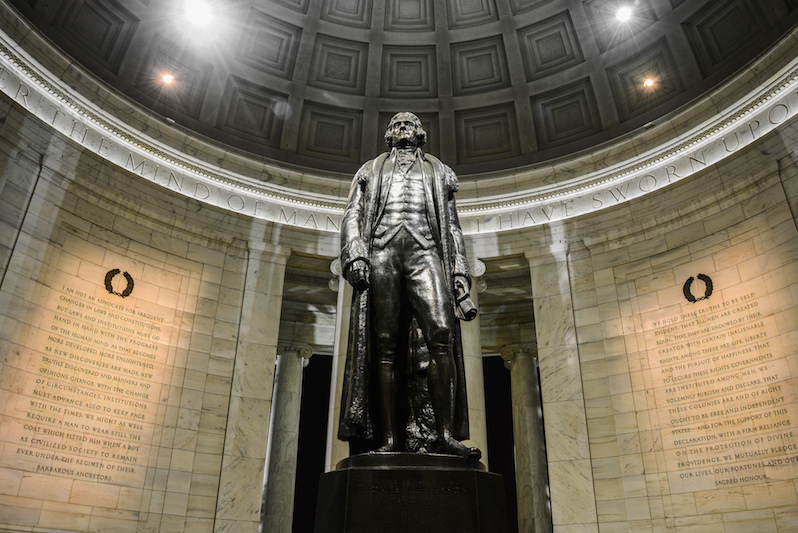

The heavy chains of “present political possibility” should be cast off. In just 10 years, it will be the 250th birthday of the United States, and it is time to create a new political system. The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Graysick / CC SA-BY 3.0)

1

2

3

The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Graysick / CC SA-BY 3.0)

1

2

3

The Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Graysick / CC SA-BY 3.0)

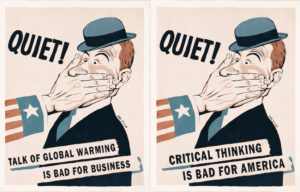

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.