Rebuilding Lives After Domestic Abuse

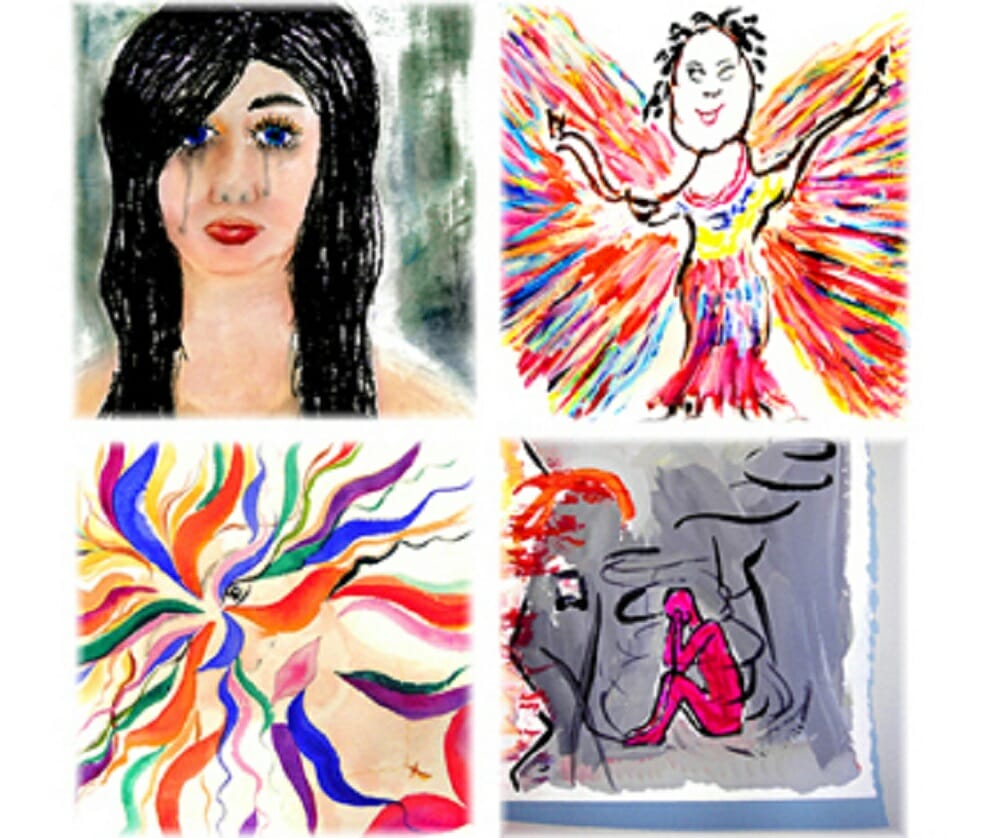

With help, and sometimes sheer determination, many women can emerge from abusive relationships stronger than ever. Vera House Survivors' Art

Vera House Survivors' Art

When a woman escapes from an abusive relationship, we call her a survivor rather than a victim because she’s lived through the hell of domestic violence.

But when it comes to psychological effects, some women remain victimized long after their bruises heal. They continue to suffer from debilitating mental health conditions that prevent them from functioning as complete human beings. Post-traumatic stress disorder is common; so are depression, substance abuse and suicidality.

On the other hand, many women are able to recover from the trauma of domestic violence and lead emotionally healthy lives. Some, like Ashley Bendiksen, discover new strength and go on to help other survivors, which adds to their own recovery.

After leaving an abusive boyfriend, Bendiksen became a motivational speaker who mentors others. “I speak so often, and I’ve made this my mission,” she says. “The unexpected consequence is that it’s given me my power back. I feel unbreakable now.”

What causes such radically different outcomes for different women?

Multiple factors have an effect, according to a fact sheet from the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health. The duration and severity of the abuse can affect the healing process, and women who experience several types of abuse—such as psychological threats, sexual attacks and other physical violence—may be at greater risk. Other factors include traumas such as childhood abuse, survivors’ personal resilience and access to services such as counseling.

Ilsa (a pseudonym) is a survivor in Orange County, Calif., who endured physical and emotional abuse for an extended period—a total of eight years in two relationships. Her first partner used physical violence. “I was 16, and he was 25,” she says. “He pushed me out of a moving car. He hauled me out of bed naked with a gun to my head. Once I woke up with a knife to my throat.”

She escaped that relationship, but then moved in with a man who intimidated her psychologically. “There was constant verbal abuse,” she says. “He liked to say he could kill me like he had one of his so-called fiancées.”

Afterward, Ilsa suffered a range of mental health problems, from insomnia to the inability to be emotionally close to others. She struggled with symptoms of PTSD almost every day for several years. “At the beginning it was bad, including nightmares,” she says. “I felt overwhelming anxiety, like I needed to be left alone. My skin crawled, and my heart raced.”

Ilsa’s condition has improved, but she continues to suffer from PTSD occasionally. “Extreme stress still causes a trigger,” she says.

Lifetime of Trauma

Previous hardship increases survivors’ risk of mental health problems. Before they get involved in an abusive relationship, “many survivors experience multiple forms of trauma over the course of their lives (e.g. child abuse; sexual assault; historical, cultural, or refugee trauma),” according to the National Center fact sheet.

Past trauma often includes growing up in an abusive household, says Roxanne Mercurio, a counselor and art therapist at the Domestic Violence Resource Center of New Mexico. “From childhood through adulthood, they’ve seen children used as pawns, name calling, intimidation,” she says. “They learn as a kid that these things are OK. And some trauma was so bad in childhood that it’s unspeakable.”

Tonya (a pseudonym), who lives in Southern California, grew up suffering verbal and emotional abuse from her father, who was addicted to alcohol and drugs. She calls him “a monster of a man.” Her mother beat her until Tonya was in her teens. “One time she beat me so bad I couldn’t go to school for three days,” Tonya says. “I was black and blue, and when I (returned to school and) dressed down for gym, people asked what happened to me. I was so embarrassed. I couldn’t say my mom beat me—again.”

Tonya’s childhood trauma has colored her adult life. She attempted suicide in the past and still has suicidal thoughts. She became an alcoholic and racked up five DUIs. Currently, she tries to control her drinking and doesn’t drive under the influence, but she says, “I’m barely controlling it, to be honest with you.”

As an adult, Tonya didn’t have an abusive partner, but she says she passed the legacy of trauma to her son. “When I became a mother, I was verbally abusive,” she says. “Now my child doesn’t want anything to do with me.”

Tonya has worked to change her behaviors, but she says, “I’m not completely healed. I don’t know if I ever will be.”

A Counseling Journey

Going to counseling can be a major factor in helping survivors heal. “These are powerful, strong women who need to learn they’re powerful, strong and in charge of their lives,” Mercurio says.

Mercurio uses a trauma-informed care approach that allows women to look at past trauma and “repair their inner child or adult,” she says. “The key is self-love and loving all the different parts of themselves that have been survivors of abuse. By doing that, they create a wholeness and repair their low self-esteem.”

For counseling to succeed, a survivor and therapist must develop a trusting relationship. “Trust needs to be learned in a healthy way,” Mercurio says.

That was the first step of the journey toward healing for Naomi Hopkins of Lompoc, Calif., who turned to counseling to address the trauma of an abusive marriage.

Hopkins’ husband had verbally and physically abused her for the 2½ years they were together. “Mainly, it was put-downs and name calling—pretty bad stuff,” she says. “There was also pushing, shoving and intimidation. He finally hit me out of anger in January 2006, and that’s why I left.”

Hopkins would have left sooner, but she says she lacked the strength—and the outside support—necessary to make the change.

“I plunged deeper and deeper into that cycle of domestic violence. I felt there was no way out and that there was no one who cared.

“A lot of people have the misconception that abused women stay in the relationship because they like it, but that’s not true. They can’t leave because it’s dangerous, or they don’t feel capable or strong enough to leave. I remember wishing someone had been there to support me or listen—not someone to solve my problems but to offer support, whether or not they agreed with my life decisions. If I had a support system, I would have left a lot sooner.”

Hopkins was a Mormon and lived in Utah for part of her marriage. “I went to church people for help, but I didn’t get help from them,” she says. “There was a lot of shame and being ostracized. The Mormons say you need to be in your marriage forever. You’re supposed to stay with (your spouse) no matter what.”

Her family members were too close to the situation to provide support, and she felt her interactions with police weren’t helpful. “Police officers need sensitivity training on how to deal with it,” she says. “I found the police professional but callous. They need to be understanding—not intimidating. I believe if they had that kind of training, more people would report abuse.”

She wishes she could have accessed other caring people for help. “The best (listener) would be a counselor, a social worker or someone else in a professional capacity who takes an interest,” she says.

Hopkins came away psychologically crippled by the abuse. “I was empty and angry—the only emotion I could feel was anger,” she says. “I became very promiscuous—even some prostitution. It was the result of feeling I wasn’t worth anything. It was really ugly and really dark for a long time.”

For years afterward, Hopkins’ personal relationships suffered. “I didn’t feel capable of being loved or loving anybody,” she says. She alienated her mother by hitting drugs and alcohol “hard”; she verbally abused her own young daughter; and she was about to lose a supportive boyfriend because of her anger issues.

In February 2017, Hopkins began individual counseling sessions, and she and her therapist began building trust. “When I first went, we started out slow,” she says. “We didn’t delve deep in the beginning. We got to know each other, and it was interesting to see how that trust evolved.”

What followed has been life-changing for Hopkins. Until she entered counseling, she had never talked to anyone about her abusive marriage. “Talking it out was the most helpful thing to me,” she says. “It lessened my anger. Once I said it out loud, it lost its power. It wasn’t a hidden secret. It was out in the open.”

Her therapist, whom she describes as “nonjudgmental and non-pushy,” encourages practicing meditation and mindfulness to control her anger. Hopkins uses HeadSpace, a guided-meditation app that helps her “focus on being present in the moment” rather than letting past trauma dictate her behavior.

Since she began counseling, Hopkins has repaired her relationship with her daughter, is working on her relationship with her mother and has learned how to interact positively with her boyfriend instead of lashing out in anger. “(My boyfriend) took a lot from me, but he stayed supportive,” she says. “We took a break and then saw each other again. As a result of my therapy, I could get close enough to him to get engaged. I couldn’t do that a year ago.”

If survivors have difficulty talking about their trauma, counselors may use other forms of healing work such as art therapy. Art—along with therapies such as music, dance and creative writing—can help in many ways, according to Cathy Malchiodi, a therapist writing in Psychology Today.

By engaging in the arts, survivors learn to regulate their emotions and achieve trauma integration, which Malchiodi describes as “a state of being able to talk or think about the trauma experience without reliving it.”

Art can be successful because it retrieves trauma memories stored in the right brain. After a traumatic experience, talking about those memories might be impossible because “the left side of brain may temporarily go offline,” Malchiodi writes.

Shorter Path to Healing

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is another therapy technique often used in place of traditional counseling.

“In this therapy, a patient selects an image related to a traumatic event and is asked to hold it in mind while engaging in back-and-forth eye movements that are led by the therapist,” according to “EMDR and the Sleep Connection,” an article by clinical therapist John Cline.

“After completing a set of eye movements, the patient is directed to note, ‘what comes up,’ such as thoughts, feelings, or other images,” Cline writes. “Over the course of the session the patient is helped to process the image and desensitize the trauma.”

While talk therapy may take a year or two to help a survivor along the path to healing, EMDR often accomplishes the same end in about half that time, Albuquerque therapist Teresa Homer says. “Not many people want to stay in (talk) therapy for two years, so they might come for six months and stop,” Homer says. “But they haven’t completed the process.”

Because EMDR works quickly, it also allows therapists at nonprofit agencies to help more survivors. Before moving to private practice, Homer was clinical director of the counseling department at New Mexico’s Domestic Violence Resource Center. The center couldn’t keep up with the demand for its counseling services, so it turned to EMDR for “the most amount of support in the shortest time,” Homer says.

Regardless of the therapeutic technique used, Mercurio says it’s important for survivors to create their own change. “They have to find their own resilience—their own inner resources—while the counselor guides them,” she says. “They have to empower themselves to be healthy, functioning human beings. They have to do a lot of the work themselves—otherwise, it’s disempowering.”

Some survivors don’t go to therapy after leaving abusive relationships. Instead, they discover reserves of strength and resilience on their own. That’s what happened to Bendiksen, who had lived with an abusive partner for two years.

Bendiksen says she entered that relationship with high hopes, but slowly became caught in a trap.

“When I first met him, he was everything I could have possibly wanted. He treated me with respect, gave me space and shared my passions. He made me feel I could really trust him, and I never thought he would hurt me.

“The abuse started off subtly. He wanted to be around me all the time. He said he enjoyed my company and missed me when I wasn’t there. It wasn’t so obvious that he was trying to control me.

“I confused it with him being loving and affectionate. I didn’t see it as unhealthy and violating my personal space and boundaries.

“Over time, I became wrapped up in making sure he was happy and satisfied. I stopped caring about my own needs—there was no room for that. I stopped caring about my identity, goals and self-worth.”

Bendiksen says it’s hard for outsiders to understand why a victim remains in an abusive relationship. “These people (abusers) aren’t abusive in the beginning. They charm you, and it all comes later, after you have feelings for them,” she says. “Then, you have good days, good weeks, good months, and that reminds you of the person you fell in love with. Other people don’t see the good side of the person that makes the victim love them and want to work on the relationship.”

As Bendiksen’s relationship progressed, the abuse worsened. “It started out as verbal and psychological abuse but built up to physical abuse,” she says. “He would hold me up against walls and throw things at me.

“I was definitely shocked and scared, but my goal at that point was to calm him down and pretend it didn’t happen. We would have conversations about his behavior over and over and over. He would apologize and say it wouldn’t happen again. When you love someone, you want to trust them. You hope if you talk about things they’ll care enough to change.”

Bendiksen lost her social support as she became more involved with her abuser. “He isolated me from a lot of people,” she says. “My parents were frustrated and didn’t know how to help me. My dad kicked me out and would no longer support me. I really didn’t have any more friends. Six months into the relationship, I didn’t talk to anyone but him and his friends.”

The process of isolation was subtle, too. “First, he would always suggest we do group activities so he could be involved,” Bendiksen says. “Over time, he would get upset if I wanted to spend time with other people. He would say if I cared enough, I would stay home with him.

“I was very afraid of his unpredictable mood swings and his response (if I went out with friends or family). It was easier to go along with him and avoid a big outburst.”

Bendiksen stayed with her abuser for two other reasons. “I always felt because I hadn’t been hit, I could manage it,” she says. “Also, I was afraid to leave because of possible retaliation. But I saw as he became angrier, it became more dangerous. When I broke up with him (and got a restraining order), he did retaliate. He pushed his way in, sat on my chest and tried to strangle me.”

Bendiksen had dropped out of college and was living in an apartment with her boyfriend. She scrambled to get back on her feet following that final assault. “After he attacked me, I knew I had to leave,” she says. “My family wasn’t supporting me, and I had no money. I picked up some waitressing shifts and found my own apartment.”

After leaving, Bendiksen displayed the frightening symptoms common to many survivors, but she also had a tremendous breakthrough.

“I definitely had anxiety—I was fearful he would still come after me because he had broken the restraining order. I felt alone, defeated and tired,” she says. “But, thankfully, I also felt sure I could go on. Along with feeling defeated, I felt hopeful again. For me, (the abuse) was one of many difficult experiences I had gone through. I was finally fed up. If I stayed a victim, he would win. I wanted to win. I chose to survive and do good in my life.”

Bendiksen can’t explain exactly how she tapped her internal strength. “It was very internal for me,” she says. “I didn’t have a support network of family and friends at the time. I didn’t know about the community resources available to me, so I don’t know how to teach other people to have that moment.”

But through public speaking and mentoring, she shares what she has learned with other survivors.

“I try to give them a positive mindset—it’s the most important thing about the survival process. I tell them to speak to themselves in a way they deserve. Instead of saying, ‘I’m worthless. I’ll never find anyone else,’ they should say, ‘I deserve better. I deserve love. I deserve success.’ I always say, ‘It’s not going to be easy, but you will get through it. Just keep going every day.'”

Finding Strength and Self-Love

As horrific as domestic violence is, some survivors not only heal but come back stronger than ever.

“The outcome is more positive than anything in their life,” Mercurio says. “They come out way ahead, knowing how to do self-care and self-love. They find those parts of themselves that are resilient and powerful that they never knew existed.”

Bendiksen went on to finish college, become an advocate for survivors and spearhead a wide variety of philanthropic activities in Massachusetts.

“A lot of abusers make you think you would be nothing without them,” she says. “I wanted to prove (my abuser) wrong. It fueled something within me that I had never discovered before. I read a quote that said, ‘The greatest revenge is massive success.’ I decided I would be massively successful. I said, ‘If he ever sees my name again, I will be massively successful—doing much more than fine.”

Hopkins, who benefited greatly from counseling, says: “I was broken down to nothing, and now I’ve been able to put the pieces back together. I’ve been through a lot, but if I had the chance to go back and change it, I wouldn’t because I’ve come out stronger and better.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.