Progressives: Don’t Scream, Organize (update)

For progressives, the question on the health care battle going forward is not whether they have a right to be angry but whether they can direct their fury toward constructive ends. This column has been updated by the author.What happened to the health care bill is outrageous, but progressives need to direct their fury toward constructive ends.Editor’s note: The following column has been revised in several places after the day’s news. The original version can be found on page 2.

For progressives, the question on the health care battle going forward is not whether they have a right to be angry but whether they can direct their fury toward constructive ends. The alternative is to pursue a temporarily satisfying and ultimately self-defeating politics of protest.

Of course what has happened on the health care bill is enraging. It’s quite clear that substantial majorities in both houses of Congress favored either a public option or a Medicare buy-in.

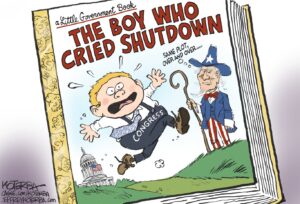

In a normal democracy, such majorities would work their will, a law would pass, and champagne corks would pop. But everyone must get it through their heads that thanks to the now bizarre habits of the Senate, we are no longer a normal democracy.

Because of a front of Republican obstruction and the ludicrous idea that all legislation requires a supermajority of 60 votes, power has passed from the majority to tiny minorities, sometimes minorities of one.

Worse, more influence in this system flows to those willing to kill a bill than to those who most devoutly want to pass one. The paradox in this case is that senators who care most passionately about extending health coverage to 31 million Americans have the least power.

That’s why Joe Lieberman held the whip hand in killing the idea of letting Americans 55 and older buy into Medicare. Unlike liberal senators such as Jay Rockefeller or Sherrod Brown, Lieberman was perfectly happy to see the health care proposal die if that was the price of getting himself into the spotlight.

What transpired was thus not the product of some magic show in which more conservative senators are endowed with mysteriously ingenious negotiating abilities while liberals are a bunch of bunglers. The whole system is biased to the right because the Senate itself — a body in which Wyoming and Utah have as much representation as New York and California — is tilted in a conservative direction. The 60-vote requirement empowers conservatives even more.

In light of this, the notion that letting the current health care bill perish would produce a more progressive bill later is preposterous. Anyone who wants to change or even abolish the Senate has my full support. But that is not an option now.

In the meantime, progressives such as Brown and Rockefeller are right to be fighting with all their might to push through this less than perfect but still remarkably decent proposal.

To vote against it, Rockefeller said when I caught up with him recently, “you have to be for not covering 30 million people … you have to be for denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions … you have to be against helping small businesses buy health insurance.” His list went on and on, pointing to the rather astonishing progress this bill makes.

Brown agrees, and suggests that progressives now need to direct their energies toward improving on the Senate’s work. Senate passage of this bill, expected later this week, will not be the final step. There will still be negotiations with the House whose plan is, in some important respects, the superior product, especially when it comes to making insurance more affordable for low- and middle-income Americans.

While the Senate’s intricate balance severely constrains how many changes it will accept — Sen. Ben Nelson, who provided the crucial 60th vote, made that clear in an interview with CNN Sunday — there is still room to maneuver. Instead of trying to derail the process, which is exactly what conservative opponents want to do, those on the left dissatisfied with the Senate bill should focus their efforts over the next few weeks on getting as many fixes into it as they can.

And then they can do something else: start organizing for the next health care fight. Enactment of a single bill will not mark the end of the struggle. It will open a series of new opportunities. It’s a lot easier to improve a system premised on the idea that everyone should have health coverage than to create such a system in the first place. Better to take a victory and build on it — to accept this plan as a “starter home,” in Sen. Tom Harkin’s apt metaphor — than to label victory as defeat.

Successful political movements prosper on the confidence that they can sustain themselves over time so they can finish tomorrow what they start today. At this moment, rage is understandable, but hope is what’s necessary.

E.J. Dionne’s e-mail address is ejdionne(at)washpost.com.

© 2009, Washington Post Writers GroupFor progressives, the question on the health care battle going forward is not whether they have a right to be angry but whether they can direct their fury toward constructive ends. The alternative is to pursue a temporarily satisfying and ultimately self-defeating politics of protest.

Of course what has happened on the health care bill is enraging. It’s quite clear that substantial majorities in both houses of Congress favored either a public option or a Medicare buy-in.

In a normal democracy, such majorities would work their will, a law would pass and champagne corks would pop. But everyone must get it through their heads that thanks to the now bizarre habits of the Senate, we are no longer a normal democracy.

Because of a front of Republican obstruction and the ludicrous idea that all legislation requires a supermajority of 60 votes, power has passed from the majority to tiny minorities, sometimes minorities of one.

Worse, more influence in this system flows to those willing to kill a bill than to those who most devoutly want to pass one. The paradox in this case is that senators who care most passionately about extending health coverage to 31 million Americans have the least power.

That’s why Joe Lieberman held the whip hand in killing the idea of letting Americans 55 and older buy into Medicare. Unlike liberal senators such as Jay Rockefeller or Sherrod Brown, Lieberman was perfectly happy to see the health care proposal die if that was the price of getting himself into the spotlight.

What transpired was thus not the product of some magic show in which more conservative senators are endowed with mysteriously ingenious negotiating abilities while liberals are a bunch of bunglers. The whole system is biased to the right because the Senate itself — a body in which Wyoming and Utah have as much representation as New York and California — is tilted in a conservative direction. The 60-vote requirement empowers conservatives even more.

In light of this, the notion that letting the current health care bill perish would produce a more progressive bill later is preposterous. Anyone who wants to change or even abolish the Senate has my full support. But that is not an option now.

In the meantime, progressives such as Brown and Rockefeller are right to be fighting with all their might to push through this less than perfect but still remarkably decent proposal.

To vote against it, Rockefeller said when I caught up with him recently, “you have to be for not covering 30 million people … you have to be for denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions … you have to be against helping small businesses buy health insurance.” His list went on and on and on, making the point that this bill represents rather astonishing progress.

Brown is of the same view, and also points to where progressives now need to direct their energies. Senate passage of this bill is not the final step. The Senate proposal, Brown said in an interview, can still be improved.

If the Senate produces a bill, there will be negotiating to do with the House, which has passed its own plan. In many respects — especially when it comes to making insurance more affordable for low- and middle-income Americans, imposing tougher regulations on insurance companies and putting caps on deductibles and co-pays — the House has the superior product.

While the intricate balance in the Senate puts severe constraints on how much it will accept changes in its bill, there is some room to maneuver. Instead of trying to derail the process — exactly what conservative opponents want to do — those on the left dissatisfied with the Senate bill should focus their efforts over the next few weeks on getting as many fixes into it as they can.

And then they can do something else: start organizing for the next health care fight. Enactment of a single bill will not mark the end of the struggle. It will open a series of new opportunities. It’s a lot easier to improve a system premised on the idea that everyone should have health coverage than to create such a system in the first place. Better to take a victory and build on it than to label victory as defeat.

Successful political movements prosper on the confidence that they can sustain themselves over time so they can finish tomorrow what they start today. At this moment, rage is understandable, but hope is what’s necessary.

E.J. Dionne’s e-mail address is ejdionne(at)washpost.com.

© 2009, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.