Privacy Is Freedom

In an excerpt from his new book, Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer points to Chief Justice John Roberts' decision in SCOTUS' 2014 cell phone wiretapping case, which affirmed that the ideas embodied in the Fourth Amendment represent the basic idea that sparked the American Revolution. In an excerpt from his new book, Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer points to Chief Justice John Roberts' decision in SCOTUS' 2014 cell phone wiretapping case, which affirmed that the ideas embodied in the Fourth Amendment represent the basic idea that sparked the American Revolution.

Detail from the cover of “They Know Everything About You: How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy.” (Nation Books)

In an excerpt from his new book, “They Know Everything About You: How Data-Collecting Corporations and Snooping Government Agencies Are Destroying Democracy,” Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer traces the Fourth Amendment’s enshrinement of privacy rights from English common law to Facebook and a defense by Chief Supreme Court Justice John Roberts.

What is the role of privacy in the twenty-first century? To the leaders of Internet commerce, whose basic business model involves exploiting the minutiae of their customers’ lives, the very idea of privacy has been treated as, at best, an anachronism of the pre-digital age. Meanwhile, those desiring to keep their personal data from prying eyes claim it as an unconditional constitutional right.

After making a pro-privacy pretense, in his company’s early years, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg began steadily advancing the argument that privacy is a luxury being willingly tossed aside by customers preferring convenience. “People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people,” he said while accepting a Crunchie award in San Francisco in January 2010. “That social norm is just something that has evolved over time. We view it as our role in the system to constantly be innovating and be updating what our system is to reflect what the current social norms are.”

Instead of viewing the protection of privacy as a business’s obligation to his customer base, Zuckerberg suggested that the very concept of personal privacy could be gradually disappearing. “[F]our years ago, when Facebook was getting started, most people didn’t want to put up any information about themselves on the Internet,” he told an interviewer at the Web 2.0 Summit in 2008.

Right? So, we got people through this really big hurdle of wanting to put up their full name, or real picture, mobile phone number. . . . I would expect that, you know, next year, people will share twice as much information as they are this year. And then, the year after that, they’ll share twice as much information as they are next year . . . as long as the stream of information is just constantly increasing, and we’re doing our job, and . . . our role, and kind of like pushing that forward, then I think that, you know . . . that’s just been the best strategy for us.

In other words, let’s keep pushing customers to give up a little more privacy every day until they have none left. This has, of course, been the norm in an industry based on customers clicking an “agree” button to approve privacy terms and conditions contracts designed to be unreadable—and to go unread. (As Sun Microsystems chief executive Scott McNealy famously said way back in 1999, “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”)

Zuckerberg went further in his 2010 statement, chastising those given to an older business model based on caution over privacy and instead praising companies (like his) that could easily rise above such obviously out-of date-concerns: “A lot of companies would be trapped by the conventions and their legacies of what they’ve built, doing a privacy change. . . . But we view that as a really important thing, to always keep a beginner’s mind and what would we do if we were starting the company now, and we decided that these would be the social norms now and we just went for it.”

An even darker defense of the end-of-privacy doctrine had been offered a month earlier by Google’s Eric Schmidt, who impugned the innocence of consumers who worry about snooping by Google and other companies. “If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place,” Schmidt stated in an interview for a December 2009 CNBC Special, “Inside the Mind of Google.”

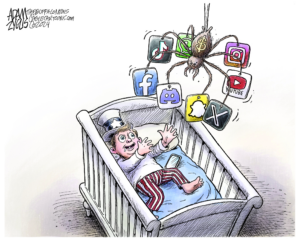

The ability of the fast-growing Internet data-mining companies to trivialize privacy concerns succeeded because the target audience of younger consumers was either indifferent to invasions of their privacy or ignorant of the extent and depth of that data collection. It was remarkable that an American social culture that had for so long been moored to a notion of individual sovereignty predicated on the ability to develop one’s identity, ideas, and mores in private, had, in a wink, become willing to surrender any such notion.

Americans had fought and died for the right to have privately developed papers, conversations, friendships, and diaries, especially in our homes. Yet here we were as a society voluntarily moving so much of that into digital spaces owned and managed by corporations we have no control over. This relinquishing of the most private information about one’s essence and aspirations became the norm in a shockingly short period, examined only lightly and in passing. As we shared more and more with ever-widening social networks, it seemed okay as long as the companies securely stored this precious data, to be used only to enhance the consumer experience. We counted on the self-interest of the corporation not to harm us, not to bite the hand that feeds.

But the Snowden revelations changed all that by exposing how easily the government could access—and indeed was accessing—our personal info. That troubling confluence between the corporate world and the state caught the public’s attention in a way that Internet companies feared might be game changing, threatening the culture of trust needed to continue gathering that data.

Also straining global confidence in Internet commerce was the shock of those outside the country who had bought into the myth that US-based multinationals were international in their obligations, but who now found them to be subservient to the whims of Washington. That was a message that US companies, up against a saturated domestic market for their products, found particularly alarming, since they depend on global growth to please shareholders.

A suddenly anxious Zuckerberg felt compelled to communicate his concerns to the president as well as to the larger public. Ten months after the first Snowden revelations, Zuckerberg posted on Facebook the following cri de coeur to air his concerns over the enduring costs of the ongoing firestorm. It is long but worth reading as a coming-of-age manifesto from one of the Internet’s wunderkinder:

As the world becomes more complex and governments everywhere struggle, trust in the Internet is more important today than ever.

The Internet is our shared space. It helps us connect. It spreads opportunity. It enables us to learn. It gives us a voice. It makes us stronger and safer together.

To keep the Internet strong, we need to keep it secure. That’s why at Facebook we spend a lot of our energy making our services and the whole Internet safer and more secure. We encrypt communications, we use secure protocols for traffic, we encourage people to use multiple factors for authentication and we go out of our way to help fix issues we find in other people’s services.

The Internet works because most people and companies do the same. We work together to create this secure environment and make our shared space even better for the world.

This is why I’ve been so confused and frustrated by the repeated reports of the behavior of the US government. When our engineers work tirelessly to improve security, we imagine we’re protecting you against criminals, not our own government.

He ended by stating that he had called Obama “to express my frustration over the damage the government is creating for all of our future,” but there is no indication the president got the message. Obama continued to let his national security adviser James Clapper lead him about by the nose while joining him in treating whistleblower Snowden, whose courage is the only reason we learned what was going on, as one of the nation’s most dangerous fugitives. Obama’s Justice Department had chosen to forget all about the Fourth Amendment that protects citizens against the unwarranted searches of both state and federal governments, as Zuckerberg’s lawyers would soon point out in court filings.

Soon after Zuckerberg’s post, his company was embroiled in a lawsuit with the district attorney of Manhattan, who had sought the private data of 381 of Facebook’s customers. In this particular situation, Facebook took the high road in defending its customers’ privacy, as the record of the company’s court filings would indicate. But the disclosure of that exemplary role on the part of Facebook in June 2014 (discussed following) was drowned out by the clamor of stories about Facebook’s own manipulation of its customers’ data in ways that many thought shameful, if not criminal. A thorough report by Robinson Meyer on June 28, 2014, in The Atlantic magazine revealed that Facebook permitted data scientists to manipulate the “news feed” of almost 700,000 of its users in a study to determine whether users’ moods could be manipulated through “emotional contagion.” As Meyer reported, “Some people were shown content with a preponderance of happy and positive words; some were shown content analyzed as sadder than average. And when the week was over, these manipulated users were more likely to post either especially positive or negative words themselves.”The study in question, which took place the week of January 11, 2012, and was published in the June 17, 2014, issue of the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indeed showed that “emotions expressed by friends, via online social networks, influence our own moods, constituting, to our knowledge, the first experimental evidence for massive-scale contagion via social networks.”

The story in The Atlantic was shared by thousands of readers and elicited numerous angry comments. The New York Times story on the study captured the essence of the outrage in its opening sentence: “To Facebook, we are all lab rats.” More negative responses to Facebook poured in—proof, one could conclude, of the emotional contagion of anger and outrage.

In a post on Facebook on that same day in June, Adam D. I. Kramer, a Facebook data scientist, fell on his sword, conceding that he wrote and designed the experiment in addition to co-writing the study with Professor Jeffrey T. Hancock and then-doctoral student Jamie E. Guillory of Cornell University’s departments of Communication and Information Science.

Kramer’s claim for the study was that “we care about the emotional impact of Facebook and the people that use our product. We felt that it was important to investigate the common worry that seeing friends post positive content leads to people feeling negative or left out. At the same time, we were concerned that exposure to friends’ negativity might lead people to avoid visiting Facebook. . . . And at the end of the day, the actual impact on people in the experiment was the minimal amount to statistically detect it. . . . [O]ur goal was never to upset anyone. . . . In hindsight, the research benefits of the paper may not have justified all of this anxiety.”

For its part, Cornell was prompted to issue a statement making clear that Hancock and Guillory merely analyzed the results of the research previously conducted by Facebook and did not have access to user data. “Their work was limited to initial discussions, analyzing the research results and working with colleagues from Facebook to prepare the peer-reviewed paper,” said Cornell.

But more disconcerting than the results of that study was the fact that Facebook had turned 689,003 of its 1.2 billion users into unsuspecting subjects in a deliberate attempt to manipulate their emotions. As New York Times tech writer Vindu Goel noted in his article, “The uproar highlights the immense control Facebook exerts over what its users see. When someone logs in, there are typically about 1,500 items the company could display in that person’s news feed, but the service shows only about 300 of them.” That is, despite the company’s endless turnout of tools that purportedly allow users to curate the content shown in news feeds, Facebook—not the user population—is the real author of our social media stories.

The totalitarian overtones of this thought-control experiment were more chilling after a year of discoveries of cooperation between the NSA and Internet companies like Facebook.

The news feed controversy exposed a Facebook reality its users might already have known if they followed the company’s critics, or read its jargon-ridden 9,000-word terms-of-service agreement. But judging from the shocked reaction, few had thought analytically about the implications of Facebook’s ordering of the data its users and advertisers generate. As Cornell communications scholar Tarleton Gillespie put it in the wake of the controversy, it left many users with “a deeper discomfort about an information environment where the content is ours but the selection is theirs.”

Gillespie spelled out the sea change in communications technology represented by social networks as a sharp break from previous models of the mass delivery of information. “On the one hand, there had been the safe and sound ‘trusted interpersonal information conduits’—namely, the post office system and the trunk lines managed by telephone companies that were designed to be neutral carriers of information but not curators prioritizing the content via an algorithm of importance.16 We expected them not to curate or even monitor that content,” Gillespie wrote. “[I]n fact we made it illegal to do otherwise; we expected that our communication would be delivered, for a fee, and we understood the service as the commodity, not the information it conveyed.”

He continued to explain that the opposite was true for broadcast programming and the content of newspapers and magazines, which were explicitly curated offerings; we were consciously choosing—and often actually paying—to consume filtered presentations produced by professionals.

Social networks such as Facebook represent a confusion of the two, however, with users generally expecting the former and instead getting an automated version of the latter. They are neither fish nor fowl, and while Facebook seems to be a neutral carrier of data, like the old post office system, it also dips into the “mail” and responds to its content by prioritizing future deliveries, attaching relevant advertising, and hiding what it considers junk.

The end result is that your information becomes the raw material for a new commodity the company manages for its own purposes—binding users ever more tightly to Facebook as their social home base on the Internet. But to monetize clicks, the company’s research will most definitely also include exploiting purchasing tastes to benefit Facebook’s true customers, the advertisers who want to sell you something. They are paying, after all; you are not.

Sheryl Sandberg, second in command at Facebook, admitted the news feed manipulations were an effort to improve commercial marketing (rather than a high-minded academic project). “This was part of ongoing research companies do to test different products, and that was what it was; it was poorly communicated,” she said. “And for that communication we apologize. We never meant to upset you.”

But the message was clear that the heads of Facebook were embarrassed not by doing something creepy and manipulative but, rather, by having been caught. Of course, they never meant to upset Facebook users by making them feel they were part of some experiment in social control. Yet this was just business as usual, albeit not something on which they want the public to focus.

As Jaron Lanier warned in a New York Times op-ed published days after the release of the emotional-contagion study, “This is only one early publication about a whole new frontier in the manipulation of people, and Facebook shouldn’t be singled out as a villain. . . . Now that we know that a social network proprietor can engineer emotions for the multitudes to a slight degree, we need to consider that further research on amplifying that capacity might take place. Stealth emotional manipulation could be channeled to sell things (you suddenly find that you feel better after buying from a particular store, for instance), but it might also be used to exert influence in a multitude of other ways. Research has also shown that voting behavior can be influenced by undetectable social networking maneuvering, for example.”

Undetectable, because the news feed feature of Facebook, notwithstanding the disclaimers of the wordy terms-of-service agreement, manages to convey a sense of automated neutrality, in much the same way Google and Yahoo do with their searches. There is a thumb on the scale that users are lulled into ignoring, “[a]nd Facebook is complicit in this confusion,” said Cornell professor Gillespie, “as they often present themselves as a trusted information conduit, and have been oblique about the way they curate our content into their commodity.”

This presents a persistent contradiction for Facebook because its basic attraction is that it is simply a reliable communication tool for friends and family (admittedly an unrealistic expectation for a service that is provided free of charge), but the company’s profit model requires it to find ever more ingenious ways to commodify a customer’s curiosity or personal data.

Furthermore, the power of social networks to define reality makes them targets for governments that have their own stake in manipulating public opinion. (China, for example, has attempted to block the use of such networks inside its borders.) The ability to alter the thinking or emotions of large numbers of people would have obvious appeal to political demagogues, and some observers were quick to connect the Facebook experiment with the US Department of Defense’s controversial Minerva Research Initiative.Launched in December 2008 with $50 million, Minerva is a tool for the Pentagon to fund academic research by theoretically independent scholars on subjects it is interested in, such as China, terrorism, and political activism, “to improve DoD’s basic understanding of the social, cultural, behavioral, and political forces that shape regions of the world of strategic importance to the US.”

Disturbingly, some of the research they commissioned seemed to be aimed at understanding how to control or prevent public dissent inside the United States through surveillance and manipulation of information flows, like those curated by social networks. When it turned out that one of those on the Minerva gravy train was the same Cornell prof who headed the analysis of the Facebook news feed study, warning flags were raised for civil libertarians.

While Cornell officials said that Jeffrey Hancock did not use his Pentagon funding specifically for the Facebook study, the “emotional contagion” survey was consistent with both his overall focus on “psychological and interpersonal dynamics of social media, deception, and language” and the study the university spearheaded, which was managed by the Air Force and designed to develop an empirical model “of the dynamics of social movement mobilization and contagions.”

The Pentagon’s project, slated to be funded through 2017, “aims to determine ‘the critical mass (tipping point)’ of social contagions by studying their ‘digital traces’ in the cases of ‘the 2011 Egyptian revolution, the 2011 Russian Duma elections, the 2012 Nigerian fuel subsidy crisis and the 2013 Gazi Park protests in Turkey,’” reported global security scholar Dr. Nafeez Ahmed, writing in the Guardian.

Hancock’s work is a clear and ominous link between market manipulation of consumer taste, Facebook’s bread-and-butter goal, and the potential ability to use those same tactics to engineer public consent for government policies. (The Air Force study focused on Twitter posts “to identify individuals mobilized in a social contagion and when they become mobilized.”) Other Minerva-funded projects cover similar terrain; examples include a study awarded to the University of Washington to research the origination, characteristics, and likely consequences of political movements as well as a study titled “Who Does Not Become a Terrorist, and Why?” that, according to Ahmed, frighteningly conflated peaceful activists with “supporters of political violence.”

Ahmed argues that NSA mass surveillance “is partially motivated to prepare for the destabilizing impact of coming environmental, energy and economic shocks.” He finds support from other concerned academics, including James Petras, Bartle Professor of Sociology at New York’s Binghamton University, who says that Minerva-funded social scientists linked to US counterinsurgency operations are involved in the “study of emotions in stoking or quelling ideologically driven movements,” including how “to counteract grassroots movements.”

In the end, the motives of Internet companies engaged in the creative exploration of their customers’ data, or those of the academics who facilitate this, may not matter very much if government agencies, in the United States or elsewhere, can simply seize that data and perform their own extensive exploration of the “contagions” involved, the better to cause or eliminate them.

In other words, the news feeds or timelines of social media can be surveilled to locate agitators and predict legal “rebellions,” and, if the next logical step is taken, can be manipulated through deletion, addition, or changes in algorithms to block the spread of dissenting or “dangerous” ideas.

In June 2014, as Facebook was attempting to deal with the controversy over its own manipulation of news feeds, the company went into court to prevent the district attorney of Manhattan from taking similar liberties with the privacy of nearly four hundred site users who were unaware of the government’s access to their data. Suddenly, Facebook, which had previously cooperated with various federal and state agencies, was on the warpath, ostensibly to protect the privacy of its clients in the post-Snowden era.

To read memorandums of law filed in support of Facebook’s case against the attorney general’s demand for data is to encounter a born-again belief in the intrinsic wisdom of the Fourth Amendment. “These warrants fail to include date restrictions or any other criteria to limit the voluminous data sought, nor do they provide for procedures to minimize the collection or retention of information that is unrelated to the investigation. The warrants’ extraordinary reach and lack of particularity render them constitutionally defective under state and federal law and should be quashed,” wrote Facebook’s attorneys. “In the alternative, Facebook should be permitted to provide notice to the people whose accounts are subject to these warrants to afford an opportunity to object to the expansive scope.”

There is an inherent irony in this language made obvious when one considers that Facebook’s own customers are never afforded an opportunity to know, let alone object to, the scope of the personal data that it has gathered on them. So, too, the fact that this vast trove of data the government is unreasonably demanding is already in the hands of Facebook, to be freely exploited for advertising sales and other sources of profit. But this irony disappears if one accepts Facebook’s argument that the Fourth Amendment provides a restraint only against government searches and therefore becomes an issue only when its agents can invade their massive collections of data.

Crucially, Facebook invoked the Fourth Amendment’s ban on warrantless searches, noting that the amendment was designed to prevent government and not corporate overreach. Clearly, if Facebook had been transparent in collecting customer data, with individuals’ explicit approval, then this would have been a matter of private consensual commerce that does not fall under the Constitution’s protections.

But in fact it is a fit matter of government regulation of business behavior, as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) pointed out in challenging Facebook’s possible mining of the data acquired in the course of its purchase of WhatsApp.

WhatsApp customers had supplied their information on the basis of that company’s privacy policy restricting such mining, meaning Facebook was possibly breaking fraud laws by violating that binding agreement. However, fraud is not a constitutional violation, and the WhatsApp customers could not claim to be suffering the loss of Fourth Amendment rights, since those apply only to intrusive or abusive government actions.

What the Fourth Amendment clearly does prohibit, as Facebook’s lawyers pointed out quite strenuously in their briefs versus the New York district attorney, is warrantless general searches by the government, and that applies even if the route to that data is through the files maintained by a third party, which in this instance is Facebook.

In this particular case, the DA was on a fishing expedition to find evidence that people claiming medical disability were cheating, a search that should have required a specific warrant. Pointing out that they were appealing the warrant’s demand that Facebook “collect and turn over virtually all communications, data, and information from 381 Facebook accounts,” and that only the holders of 62 of those accounts were even charged with any crime, Facebook correctly argued that the prosecutor’s overreach represented a clear violation of the Fourth Amendment protections to which Facebook’s clients were entitled.

“The trial court’s refusal to quash the bulk warrants was erroneous and should be reversed. The Fourth Amendment does not permit the Government to seize, examine, and keep indefinitely the private messages, photographs, videos, and other communications of nearly 400 people—the vast majority of whom will never know that the government has obtained and continues to possess their personal information,” the brief stated. “Nor does the First Amendment permit the government to forbid Facebook from ever disclosing what it has been compelled to do—even after the government has concluded its investigation.”

That last objection, to a government agency being able to require that a private company not inform its customers of possible violations of their rights, is particularly crucial. By what perversion of the hallowed American concept of an informed citizenry ever vigilant to deprivations of their freedom could such a gag order not violate the meaning of the First Amendment?Facebook was appealing to the New York State Supreme Court appellate division to overrule the decision of a lower trial court that held the gag order valid, but the same argument could be made against a similar order imposed on communications companies by the federal courts that prevented them from discussing NSA and other government-agency spying on citizens.

One key issue here is whether third parties like Facebook and Google have legal standing to protect their customers’ constitutional rights. Facebook’s lawyers argued that permitting the government to rummage through the data collected in Facebook accounts would be analogous to government agencies hiring a private contractor to conduct a broad warrantless search in someone’s home, a clear violation of the Fourth Amendment: “The Government’s bulk warrants, which demand ‘all’ communications and information in 24 broad categories from the 381 targeted accounts, are the digital equivalent of seizing everything in someone’s home. Except here, it is not a single home but an entire neighborhood of nearly 400 homes. The vast scope of the government’s search and seizure here would be unthinkable in the physical world.”

This extension of the constitutional protection against unreasonable searches in the physical world to the digital world is, of course, the heart of the modern challenge to government surveillance overreach. Obviously, the founders did not have in mind a “digital home.” However, in June 2014, the Supreme Court delivered a groundbreaking decision extending Fourth Amendment protection to the data on a mobile device found on or near an arrested person. This victory for civil libertarians clearly set a precedent for protecting other digital collections, including those housed on Facebook.

As Chief Justice John Roberts argued in Riley v. California, the information digitally housed on a mobile device—or, by extension, a Facebook page—is so vast that searching through it represents a warrantless search without probable cause that is banned by the Fourth Amendment. An individual therefore has a reasonable expectation that this material will be treated as private and searched only pursuant to a specific warrant alleging probable cause of a crime.

The lack of such specificity, obviously not present in the district attorney’s broad scan of the entire data collection housed on almost 400 Facebook users’ pages, denies the essence of the constitutional protections. As Justice Roberts wrote: “Modern cell phones are not just another technological convenience. . . . With all they contain and all they may reveal, they hold for many Americans ‘the privacies of life.’”

So, too, do Facebook pages represent revelations of the privacies of life. The Supreme Court marker on privacy established that the digital world, instead of reducing the constitutional protection of privacy to a quaint anachronism, has in fact rendered those protections far more compelling, due to the vast amounts of data in digital collections.

“Before cell phones,” Roberts wrote, in an opinion with obvious ramifications for all other digital databases, “a search of a person was limited by physical realities and tended as a general matter to constitute only a narrow intrusion on privacy. . . . Today it is no exaggeration to say that many of the more than ninety percent of Americans who own a cell phone keep on their person a digital record of nearly every aspect of their lives—from the mundane to the intimate.”

This extension of the protections that the founders afforded to even the most meager of traditional homes—treating a hut as a castle in establishing privacy as a fundamental human right—to homes in the digital world is perhaps the most dramatic evidence that the Constitution is a living document, fully capable of being adapted to a vastly changed world. Not doing so, Roberts argued, “is like saying a ride on horseback is materially indistinguishable from a flight to the moon.”

Instead of concluding that modern technology renders privacy demands untenable, Roberts argued that those protections had to be expanded to provide meaningful privacy protection in a technologically far more invasive era. “The sources of potential pertinent information are virtually unlimited,” he wrote, noting that failing to restrict warrantless searches of the digital home “would in effect give ‘police officers unbridled discretion to rummage at will among a person’s private effects.’”

In their appeal, Facebook’s attorneys demonstrated just how invasive that unbridled rummage could be. Even many of the 1.2 billion users of Facebook forget how much of themselves they are revealing:

People use Facebook to share information about themselves, much of it personal. This information often includes:

• The person’s age, religion, city of birth, educational affiliations, employment, family members, children, grandchildren, partner, friends, places visited, favorite music, favorite movies, favorite television shows, favorite books, favorite quotes, things “Liked,” events to attend, affiliated groups, fitness, sexual orientation, relationship status, political views;

• The person’s thoughts about: religion, sexual orientation, relationship status, political views, future aspirations, values, ethics, ideology, current events, fashion, friends, public figures, celebrity, lifestyle, celebrations, grief, frustrations, infidelity, social interactions, or intimate behavior;

• The person’s photographs and videos of: him- or herself, children/family, friends, third parties, ultrasounds, medical experiences, food, lifestyle, pets/animals, travel/vacations, celebrations, music, art, humor, entertainment;

• The person’s private hardships meant to be shared only with friends; and

• The person’s intimate diary entries, including reflections, criticisms, and stories about daily life.

This is just the sort of personal information the Fourth Amendment was designed to protect against warrantless searches. But given Facebook’s acknowledgment that it is in fact collecting and storing such information, one has to ask why? Why collect such detailed and intimate information if you have already learned that the federal government, as represented by the NSA and other agencies, can routinely tap into that information? What is the likelihood of governments abroad doing the same? If Facebook and other Internet companies cannot guarantee the security of the data they collect, or even, as this case demonstrates, alert their customers to the risks involved, why collect or store the data at all?

The answer becomes apparent in what we have learned of the basic business model that ensures the profitability of most Internet companies. The data is collected not because government agencies require it but, rather, because the companies themselves want to exploit it, for profit. Consider the ethical implications of doing just that under an overtly totalitarian government enabling a degree of surveillance of the individual of unprecedented proportions. Perhaps Facebook trusts the US government more, but isn’t that a choice its customers should make about the use of their data? In any case, Facebook has already shown that it is in a position to manipulate the choices its customers make, and what assurance can the company provide that it is impervious to any government’s use of that same set of manipulative tools?

While Facebook, Twitter, and other social media companies have been applauded for indirectly helping dissidents in countries like Egypt and Ukraine by providing a decentralized, free, “real-time,” and difficult-to-disrupt alternative communication system, what assurance can they give that those activities have not been appropriated by the very governments the protesters sought to challenge?

The reality is that most of us spend our days freely surrendering personal data out of convenience, whether to enhance a shopping experience or to build a friendship, while in denial—or simply unaware—of the fact that at the same moment all of it is being made available to government officials whose motives are inscrutable and potentially repressive.In order to conform to the fourth amendment’s restrictions on unreasonable searches, wiretapping phone conversations has long been carefully restricted by court rulings, whether conducted by private detectives or government agents. All of the world’s democratic governments, even without the specific restraint of that amendment, manage to strictly regulate the physical taps placed on phone lines to listen in and record conversations.

In the predigital age, physical intrusion on phone lines was required to intercept calls, but, today, undetected copying of signals has made the process much easier. So much so that in 2007 Google, in the course of cruising neighborhoods with vehicles designed mainly to collect photographic images to complement Google Maps, also had the ability to pick up and record data from homes connected to Wi-Fi networks. Google’s equipment was able to collect basic data from those network connections, “location-based” service IP addresses, and payload information including usernames, personal emails, passwords, and documents.

By May 2010, when confronted over this practice, Google admitted it had inadvertently collected six hundred gigabytes of such data in thirty different countries. Several class action lawsuits were filed accusing Google of having violated the federal Wiretap Act. Google lost the case both in district and appellate courts, and in June 2014 the Supreme Court refused to overturn the lower-court decisions and allowed the case to proceed.

The Supreme Court decision, coming a week after its sweeping affirmation of privacy protection for mobile devices obtained by police during an arrest, was interpreted as a shift in direction by the high court toward a reaffirmation of the importance of privacy in the digital age. Its significance for Google was less about tapping into home networks with its Google mapping trucks, which the company had agreed to stop doing, and more about important projects the company was launching that had even clearer privacy issues. As the New York Times reported, the court’s ruling “[undermined] the search company’s efforts to put a troublesome episode to rest even as it plans to become more deeply embedded in consumers’ lives.”

That last phrase is the rub. In an earlier time, the General Electric Company boasted that “progress is our most important product”; it can fairly be argued that a comparable slogan for Google today could replace progress with intrusion. Expansion plans at Google involve more effectively mining ever-larger collections of data. The Times report noted why the Supreme Court’s increased attention to privacy came at an awkward moment for the company: “Google’s annual developers conference last week showcased the company’s wide-ranging agenda to expand its technology from desktop computers and mobile devices to the home, the body, and vehicles. Google’s new devices will communicate and share data, requiring a great deal of trust by users that all this information will not be used in unauthorized or unexpected ways.”

This is a concern of consumers throughout the world, and it has been greatly enhanced in the aftermath of the Snowden revelations. Suddenly, the arrogant insistence of Google’s Schmidt or Facebook’s Zuckerberg about privacy being merely an anachronistic obsession of the technologically primitive, the perverted, or the outright criminal begins to ring hollow.

For much of human history, the line between the government and the private individual was quite clearly marked, whether under rule of the British Crown or in the new republic born in the rebellion of the colonies. Arguably, the clearest distinction between Anglo-Saxon legal experience and its alternatives resided in a profound respect for the innate rights of the individual against societal sources of power, be they derived from church or government.

The English common law that restrained the crown and informed the mindset of the American colonialists contained the seeds of a notion of individual space, an inviolate personal sovereignty that guided the writing of the Fourth Amendment into the Bill of Rights. One’s house, as humble as that dwelling might be, was safeguarded from the warrantless searches by agents of the crown, and when that right came to be ignored by the English administrators over the American colonies, it sparked the revolution as much as any factor.

That was the judgment of no less an expert on the origins of the American Revolution than a young John Adams, who witnessed the patriot James Otis delivering a speech denouncing the British Crown’s use of general warrants and writs of assistance to invade the homes of colonialists. Chief Justice John Roberts cited that incident as foundational in offering his majority opinion in the mobile devices decision:

In 1761, the patriot James Otis delivered a speech in Boston denouncing the use of writs of assistance. A young John Adams was there, and he would later write that “every man of a crowded audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take up arms against writs of assistance.” According to Adams, Otis’s speech was “the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born.”36

By positioning the right to privacy so clearly as a motivation for the break from English rule and the establishment of the republic, Roberts offered the clearest defense of a constitutional protection for privacy, a word actually absent from the Constitution itself. With that opinion a year after the first revelations by Edward Snowden regarding the enormous loss of privacy to government surveillance, a unanimous majority of the Supreme Court unexpectedly drew a firm line in defense of privacy as a constitutionally protected right.

The justices did this not by addressing the abuses of privacy by the NSA, which would have required significant self-criticism on the part of the court, since Chief Justice Roberts was responsible for appointing judges to the FISA court that approved the scope of NSA spying. Instead, this same Roberts wrote a dazzling opinion in the cell phone case that enjoyed unanimous support across the ideological divide that has defined this court in recent decades. His defense of privacy in the age of the Internet set as clear a standard on the subject as the nation has ever enjoyed through its judicial system.

Prior to the Roberts opinion, the perception had been growing in the burgeoning Internet industry—which profited so mightily from the exploitation of privacy—that the very notion of privacy was an anachronism. Since the massive flow of previously private data was essential to the new tools and toys provided free of charge by firms like Google and Facebook, the right to mine that data was simply their payment in return.

The corollary justification for the end of privacy was in part a technical one: the data stream would be too costly and difficult to restrict in the name of privacy; the very vastness of the data collected had become the compelling reason to ignore demands for protection of individual privacy by granting consumers meaningful control over their own data. That was a judgment made by most of the lower courts, including the two that had ruled in the cases reviewed by the Supreme Court that formed the basis of the Roberts opinion.

But what Roberts did, much to the surprise of industry lawyers, was to stand the complexity argument on its head. He asserted that it was precisely the scope of the data collected in the case of devices acquired by police during an arrest that made it unwise to allow those same police to search the phones’ various stored databases. This landmark decision provides an unequivocal answer on the critical role of privacy in the conception of the Fourth Amendment. Roberts did this in his conclusion by reminding us that because of the most rapid of technological changes, the threat to privacy has never been greater.

The question that Roberts’s decision left unanswered is to what degree this broad extension of cell phone privacy protection applies to the even larger collections of similarly personal data held by federal agencies, beginning with the NSA. Until the Snowden revelations, there was no serious national debate or understanding about the scope of the federal government’s assault on privacy in the digital age. But now that issue, of far greater consequence but organically quite similar to the one dealt with by Roberts in his decision, strongly and clearly demands the court’s attention.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.