Privacy by Design

Nicholas Merrill is tired of waiting for Congress to protect Americans' privacy online So he plans to force the matter by changing the way telecommunication companies do business So he plans to change the way telecommunication companies do business.

NEW YORK — Nicholas Merrill wants to change the world. So he tells me over rice and beans at Lupe’s East LA Kitchen in Soho, roughly a dozen blocks from where the World Trade Center once stood. He is perfectly serious. At 39 years old, with thick blond hair, a goatee the color of shaved carrots and the zeal of an idealist half his age, he describes his plan to rework the Internet landscape to protect the privacy and speech rights of individuals and organizations.

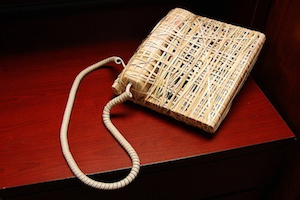

Merrill achieved national fame in August 2010 when he was partially released from a gag order forbidding him to discuss with anyone the details of a secret demand for information sent to him by the FBI six years earlier. When he got the order, Merrill was running a small telecommunications company in New York City, providing Internet access to political organizations such as the progressive radio show “Democracy Now!” and the New York Civil Liberties Union, as well as a number of corporate clients. The letter, hand delivered to Merrill’s office by an FBI agent, demanded that he give up private records detailing some of his clients’ online activities and speak of the order to no one, including presumably his lawyer.

The FBI has issued nearly 300,000 “national security letters” to banks, telecommunication companies and other organizations since the Patriot Act expanded their use in 2001. The agency maintains that each request pertains to potential threats to the United States, though it appears that no single letter has yet prevented a terrorist attack. Official challenges to the practice seem to number in the single digits, but as they have been filed mostly in secret, their exact number is impossible to know. We do know, however, that Merrill’s case is among them.

Merrill challenged the constitutionality of the national security letter’s prohibition on talking, and during a years-long court battle, Congress amended the law to allow recipients such as Merrill to discuss the letters with their lawyers. In 2007 Merrill penned an anonymous letter about his experience for The Washington Post. When his gag order was lifted, he was allowed to discuss the issue with the public openly. But for Merrill, these victories were not enough.

Out of his experience with the FBI, Merrill conceived of The Calyx Institute — a nonprofit “research, education and legal support group” with two objectives. First, to inform the public and shape policy conversations about privacy and freedom of expression on the Internet; and second, to provide the basis for an affordable, state of the art Internet service provider, a for-profit subsidiary that would use the institute’s own security software to protect users’ digital privacy from the prying eyes of identity thieves, data-mining businesses and governments.

In addition to agitating for privacy rights through Calyx, Merrill says his ISP would protect every piece of information a user’s computer or telephone sends out — browsing activity, emails, instant messages, phone calls, text messages, etc. — by scrambling the data in a process known as encryption, which makes the information unreadable to whoever might capture it. (The current practice of most telecommunication companies is not to encrypt data at all.) And here’s where Merrill’s innovation comes in: His ISP would not possess the “keys” that are needed to unscramble the data. Only his customers would.

This is a potentially revolutionary idea for the telecommunications industry. In 2005, The New York Times reported that major Internet and telephone companies — later revealed to include AT&T, Verizon and Sprint — helped the Bush administration spy on Americans in the years after 9/11 by simply handing over customer records. This would be impossible under Merrill’s model. Law enforcement agencies would have to go to individuals directly or spend vast amounts of time and resources trying to unscramble the encryptions.As federal law enforcement has enjoyed virtually unlimited access to customer records over the last decade, it would seem unlikely that lawmakers would be willing to permit what Merrill proposes. But government agencies at the regional, local and federal levels stand to gain from Merrill’s innovation as well. “Privacy and cybersecurity are two sides of the same coin,” he explains, suggesting that he can keep officials’ data safer than it currently is. “I’m not at war with the FBI,” he says. “I’m for their mission. I want them to catch criminals. I just don’t want them to undercut the rule of law or undermine the Constitution.”

Merrill’s potential clientele extends even beyond government and those on whom it spies. Businesses, including big banks and defense contractors, have an interest in protecting trade secrets. Hospitals house sensitive patient records. Lawyers need to ensure client-attorney confidentiality. Journalists want to guarantee they can protect the identities of anonymous sources. And celebrities would like to feel safe from the compulsive prying of some tabloids.

In addition to these realities, there is evidence of widespread and growing concern about identity theft and privacy on social media sites. Merrill says these trends suggest there are aspects of privacy that existing companies have ignored, and for which a new, profitable market could be made. If he can prove this is so with the success of his ISP, he believes he can pressure the industry’s giants to adopt the same practices. If he succeeds, he will have rewritten the industry’s standard practice using market forces trusted and cherished by capitalists, and will have left a stalled Congress and the courts in his dust.

Merrill already has a broad base of support from people in business and government. So far, he has assembled a board of advisers that boasts an Apple executive, a retired National Security Agency analyst and a Republican congressman, as well as civil rights lawyers, digital security experts and privacy activists.

Before he can make his ISP a reality though, Merrill has to raise more than $1 million. This is a major hurdle, in personal and legal respects. Out of concern that a prevailing interest in profits drove the major telecom companies to go along with the Bush and now the Obama spying program, Merrill wants to incorporate his business as a nonprofit.

“From my point of view, keeping it as a nonprofit would help eliminate financial incentives to screw over customers,” Merrill says. But the Internal Revenue service won’t grant an Internet service provider nonprofit status. So Merrill is being forced to tangle with the very market forces he fears.

To that end, he has been advised to seek help from the technology-minded venture capitalist community of Northern California. And there lies a personal problem. Today’s venture capitalists are almost all economic libertarians — people who think government should leave them and their money alone. Although Merrill’s privacy designs appeal directly to their desire for personal freedom, his humanitarian ambitions do not.

“They want to understand that it’s a business,” he says. An airtight business plan could get Merrill the startup money he needs, but it could also mean the loss of control over his company. And that’s something Merrill is not willing give up.

“I’m worried that I will one day hit a fork in the road and have to choose one path or the other,” he says between sips from his Jarritos soda, with his plate scraped clear. “That I’ll have to choose between what’s good for business and what’s the right thing to do. All these telecos and Internet service providers, they hit that and did what’s good for business. And that’s what I’m concerned about, that if you become a for-profit business and care more about money than principle, you’ll be co-opted. And I’m trying to stay true to my principles no matter what, because that’s the whole purpose of this.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.