Playing President

Don't miss Robert Scheer's new book: "Playing President: My Close Encounters with Nixon, Carter, Bush I, Reagan, and Clinton--and How They Did Not Prepare Me for George W. Bush." With a foreword by Gore Vidal

Don’t Miss Robert Scheer’s New Book:

“Playing President: My Close Encounters with Nixon, Carter, Bush I, Reagan, and Clinton–and How They Did Not Prepare Me for George W. Bush”

(With a foreword by Gore Vidal)

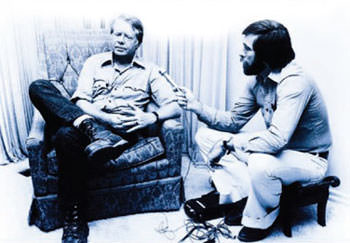

Scheer’s interviews with and profiles of U.S. presidents have shaped journalism history and had a tangible impact on national debate — such as the eminent 1976 Playboy interview in which Jimmy Carter, the then-presidential candidate, admitted to lusting in his heart; and the 1980 L.A. Times interview with Bush I, in which he confessed to Scheer his dream of a “winnable nuclear war.”

Scheer, whom Joan Didion called “one of the best reporters of our time,” offers with this book unparalleled insight into the presidential mind. Through both new writings and reprinted material, Scheer analyzes every administration from Nixon to George W. Bush, offering insights that will surprise the reader — particularly those with rigid preconceptions about the decision-making processes of our leaders.

In the pages that follow, Truthdig presents the full-text version of Scheer’s introduction, along with a foreword by celebrated man of letters Gore Vidal.

Scheer covered presidential politics for the Los Angeles Times for thirty years. He is the author of six books, including With Enough Shovels: Reagan, Bush, and Nuclear War and America after Nixon: The Age of the Multinationals; and co-author of The Five Biggest Lies Bush Told Us about Iraq. He is a clinical professor of communications at the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California. Scheer is a nationally syndicated columnist, editor of Truthdig.com, a contributing editor of the Nation, and cohost of NPR-affiliate KCRW’s Left, Right, and Center.“Playing President” is a joint Truthdig / Akashic Books publication.

Foreword

by Gore Vidal

The twentieth century produced a great deal of writing about American politics, much of it bewildered when new notions like empire started to sneak into nervous texts whose authors were not quite certain if “empire” could ever be an applicable word for the last best hope of earth.

The bidding then changed dramatically after World War Two, when Harry Truman armed us with nuclear weapons and gave us an icy sort of permanent war against Godless Atheistic communism, as personified by Joseph Stalin, standing in for Hitler, whom we had got rid of with rather more help than we liked to admit from the new world demon Stalin. How, why did Truman lock us all into a national security state, armed to the teeth? The simple story was dread of communism everywhere on the march, but those of us who had served in World War Two knew as well as our political leaders that the Soviet Union, as of 1950, was not going anywhere very soon: They had lost twenty million people. They wanted, touchingly, to be like us, with consumer goods and all the rest of it.

What actually happened was tragic for the Russian people and their buffer states: Truman, guided by that brilliant lawyer Dean Acheson, was quite aware that by 1940 the world Depression of the early ’30s had returned. The New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt had largely failed. What was to be done? FDR took a crash course in Keynesian economics. As a result, he invested $8 billion into re-arming the United States, in order to hold our own against the Fascist axis of Germany, Japan, Italy. To the astonishment of Roosevelt’s conservative political enemies, the U.S. suddenly had full employment for the work force and a military machine of the first rank with which we were able to defeat Fascism, and just about anyone else who defied us.

Truman and friends learned and never forgot an important lesson: It was through war and a militarized economy that we became prosperous with full employment. After victory in Europe and the Pacific, Truman himself began to play the war drums. Stalin was menacing Turkey and Greece (Acheson threw in nearby Italy, and why not France?). We must stop the rising Red tide, while acquiring that era’s latest propaganda toy, a TV set. This wearisome background was well known to historians like William Appleman Williams, but hardly suspected by too many of the usual publicists of the American way of life.

Robert Scheer has had the good fortune to observe first-hand the last half-dozen Presidents, from Nixon to “W”. He has also had the perseverance as a journalist to insist that he be able to conduct one-on-one conversations with the odd sort of men who were playing (or trying to play) President. This makes for a fascinating immediacy in the book at hand, particularly when he is giving his protagonists a harder time than they had expected. Scheer has always suspected that he would be one of the last journalists able to use the print medium fully in the electronic age that had dawned around 1960.

Scheer makes a telling analysis of Nixon and his “frozen smile,” with the comment that “despite being unquestionably the best prepared of all modern Presidents before assuming office, it was his indelibly awkward and secretive style that did him in.” Scheer is impressed by this President’s mind despite himself, as was Walter Lippmann, whom I once teased for supporting Nixon. Walter was serene: “I only know,” he said, “if I had a difficult lawsuit on my hands, I would go to him as a lawyer. He presents you an entire case before your eyes: He is simply brilliant, unique in public life.”

Print journalism is a challenge to the writer’s intelligence, as well as to that of his subject. Of course, few journalists and player Presidents are up to Scheer and Nixon. Yes, Nixon did much that was evil along the way (Cambodia, Watergate), but he usually managed to harm himself most — a form of good manners. He was primarily interested in foreign affairs and the opening up to China; dtente with the Soviets; these were significant achievements, and he had no strong domestic policies, which should have been a great relief for Us the People. No wartime tax breaks for cronies is quite enough for us to applaud him in other roles.

Presidents are trapped in history as well as in their own DNA codes. After Watergate, Nixon starred as Coriolanus for a while, but when he saw that this got him nowhere, he realized he was so steeped in blood that he could not turn back, so he went on as Macbeth, to our benefit at times. Scheer is not the first of our journalists to recognize how like classical players the Presidents tend to be if they have the right war or disaster to contend with. Scheer is generally good-humored about them, though Bush I’s implacable self-love seems to rub him the wrong way; also, Reagan’s rambling does not get either of them very far, yet Scheer has grasped what few others have: Mrs. Reagan’s importance not only to her somewhat listless husband but to our country, where she seems to have understood before other politicians that the Cold War was getting us nowhere.

Scheer had problems with Jimmy Carter and, perhaps, with Southern politicians in general. He struggled with the man’s compulsive fibbing about himself and his place in an imaginary Plains, Georgia, which kept changing to fit his restless re-imagining of his career, recalling homely barbershop quartets as well as killer rabbits at large in catfish ponds. Scheer had an edgy time with Carter, but it was to Scheer that Carter confessed he had lusted in his heart for ladies, causing much of the nation to admire and smirk.

Scheer concedes Clinton’s brilliance as a player but frets over (as many of us did) “the end of welfare as we know it.” It is with this President that Scheer is most interesting, largely because Clinton is as intelligent as he, at least on the subjects they discuss. Clinton has dared occasionally to touch the third rail of American political discourse: the superiority of other nations’ economies to that of America the Beautiful and the Earmarked.

Scheer: Some now blame the Europeans and Japanese for our problems and call for protectionism. Are you sympathetic to such calls?

Clinton: But to be fair, the biggest problems we have in maintaining the manufacturing base are our failures to work together to achieve high levels of productivity, to control health care costs, to have a tax system which is pro-manufacturing. Our tax system now is anti-manufacturing. And it was during the Reagan/Bush years. I think, you know, it rewarded money making money and not production, not jobs, not goods, and not services.

Scheer: Well, that’s what we say now. But when the last tax-reform package was passed, many Democrats supported it. It was supposed to help production.

Clinton: I never thought it would . . . You know, the elemental principle of taxation should be [that] people should pay according to their abilities to pay. And you should have incentives that do specific things. Those ought to be the two driving, in my view, principles of the tax system.

This is very grown-up stuff.

The final chapter, perhaps in every sense, deals with George W. Bush. Scheer confesses he was ill-prepared for someone who seems to have no idea of, or interest in, playing President, as opposed to playing “Wartime President,” easily the trick of the week when Congress has modestly declined to declare war on anyone.

Certainly, with these observations on a section of our history, Scheer joins that small group of journalist-historians that includes Richard Rovere, Murray Kempton, and Walter Lippmann.

Next Page (from Scheer’s introduction): “The problem is that in our system, as opposed to a parliamentary one, the presidential candidate’s performance is a solo act. The basic test is not that of a leader emerging from a pack made up of peers; instead, it revolves around a performer and a largely untutored electorate that is his jury and his audience. “

Introduction

by Robert Scheer

Playing president is not a book title selected casually, but a distilled opinion gleaned over forty years of journalism, covering our most important democratic exercise. After decades spent interviewing dozens of leading presidential candidates, including those who ended up in the highest office, I came to the conclusion that the process endured in obtaining electoral power tends to be the controlling influence on the candidate’s behavior once in office.

As sailors like to say, the journey is the destination, and for politicians with presidential aspirations, the experience of running for one office after another until they obtain the final prize informs as well as deforms their conduct. The problem is that in our system, as opposed to a parliamentary one, the presidential candidate’s performance is a solo act. The basic test is not that of a leader emerging from a pack made up of peers; instead, it revolves around a performer and a largely untutored electorate that is his jury and his audience.

Whereas a parliamentary leader is pushed by the process of selection to grow in ways that are positive to governance, with policy substance stressed over rhetorical style, in the American presidential system, the electoral process stupefies rather than educates, undermining — indeed, assaulting — the capacity of the politician to consider public policy in ways that are truly thoughtful. In the uniquely grueling and essentially mindless process of our system, serious issues become little more than grist for the pollsters’ mills, and substantive alternatives are reduced to slogans to be bandied about for electoral convenience and television sound-bite advertising.

I’m certain that this last sentiment will elicit a stridently defensive response from those who celebrate what they perceive as the rough-and-tumble of the American system, a robust and healthy exercise compared with the alternatives in other representative governments. Surely, those other systems have their problems, and I am not advocating that we change our constitutionally enshrined procedures for some idealized alternative. I am merely warning of the pitfalls in our presidential electoral process as I have observed them over and over again. It is a process that is intellectually dishonest and inevitably deleterious to the best interests of the voters.

All of the leading presidential candidates that I have interviewed, from Democratic Senator Gary Hart of Colorado to Republican Senator Bob Dole of Kansas, have been honorable individuals who sacrificed a great deal in their attempts to succeed at what is an extremely challenging ordeal. Whether it was John Anderson, the Republican Congressman-turned-Independent, or civil rights activist Jessie Jackson turned perennial Democratic Party candidate, these men for the most part struck me as basically well-intentioned in their eagerness to serve the nation. The fundamental hazards are in the process itself: that numbing effect of a modern mass media-observed campaign that requires such an incredible high-wire act — balancing fundraising with integrity, superficial sloganeering with profound commitment, and homogenizing the entire unwieldy package into a marketable commodity — that in the end, the candidate is transformed into a caricature who has difficulty remembering from whence he came.

That, of course, is the opposite of what the founders of the American system had in mind when they rooted our representative democracy in accountability, with even the smallest local village subject to the scrutiny of a media that was everyman, as personified by the proprietor of the penny press and the town crier.

Thomas Jefferson extolled the central importance of the media, declaring, “I would rather have free press and no government, than a government and no free press.” Journalists were by no means presumed virtuous; they were often considered vile, intemperate, and cursory in their observations. Yet what defined the media in the infancy of the nation was variety, made possible by a press that thrived in conditions of undercapitalization. Famed media critic A.J. Liebling once wrote, “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one,” and in the time of Jefferson, that group included much of the electorate.

Today, the opposite is obviously the case, with media ownership enormously costly and concentrated in a very few centers of capital. Perhaps the Internet will change that; already there are signs that the blogosphere, when it is not merely mischievous noise, is revitalizing the democratic process. After all, money is often less important than spunk as the key ingredient to the success of a website. But the contrary tendency in the period of time during which I interviewed the presidential candidates in this book was increasingly toward larger and more suffocating media conglomeration. For this reason, there is something anachronistic about the interviews I conducted, as they were produced for print outlets even while the electronic media was beginning to fully assert its dominance. It is now extremely rare for a print journalist, accompanied only by pen and paper and a tape recorder, to be granted adequate time to assess a candidate’s ability to reflect on the issues of the day.

In the introductions to each of the following sections, I attempt to provide some insight into how my exchanges with the men who served as President came to take place, and what was learned in the process. In the last section on President George W. Bush, I struggle to come to grips with the one recent President who was never subjected to such a test, from me or anyone else. While I did spend some time around him and the rest of the Bush family entourage while reporting on his father’s campaigns, he is the one President here who I never interviewed on the public record. No matter, George W. Bush is, for better or worse, the first truly electronically projected President.

Robert Scheer Los Angeles, California March 2006

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.