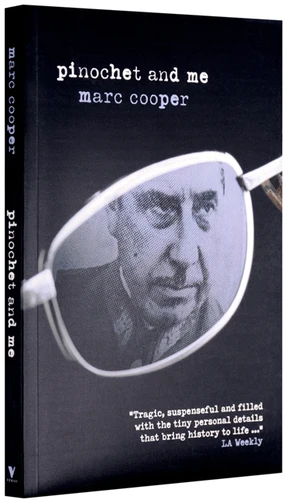

Pinochet and Me: A Chilean Anti-Memoir

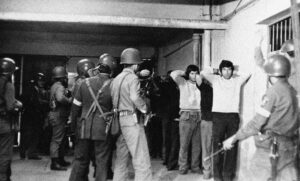

In this excerpt, journalist Marc Cooper chronicles his experience in Chile during the Pinochet coup. The Moneda Palace in Santiago getting bombed during the 1973 U.S.-backed coup. Photo / AP File

This is Part of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

The Moneda Palace in Santiago getting bombed during the 1973 U.S.-backed coup. Photo / AP File

This is Part of the "Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed" Dig series

Journalist Marc Cooper went to Chile in 1971 as a young radical student. Within a year he was working as translator to elected Socialist President Salvador Allende. In September 1973, 50 years ago, the Chilean military and police, backed by the CIA, conspired to overthrow Allende and establish a brutal military dictatorship that lasted 17 years. Thousands were killed and tortured; tens of thousands were exiled.

The following, excerpted with permission from Cooper’s book “Pinochet and Me: A Chilean Anti-Memoir,” courtesy of Verso Books, details how Cooper was caught in the sweeping violence of the coup, how he survived it and how he escaped Chile eight days later. Truthdig will host a livestream event with Marc Cooper and Suzi Weissman on Wed. May 17 at noon (PDT) — click here for more information.

7 a.m., Tuesday September 11 1973

The fledgling Santiago sun and the transparent sky, the fresh spring chill in the air and the blossoming jacaranda made that Chilean morning glorious. As I stood in the yard of my friend Melvin’s suburban house in Santiago and glanced at the lingering snowcaps on the Andes towering right behind me, as I sucked the fragrant, misty air into my lungs, I resolved I would, from that moment forward, make a sea change in my life. Quit smoking, cut back on drinking, get to bed before 3 a.m. and start rising earlier so as to enjoy more frequently these morning wonders.

I had gotten up early because my Chilean residency visa expired that day and I needed to renew it. For a year now I had been working as a translator to Salvador Allende, and in this capacity I was scheduled to travel with him the next week.

I knew that presidential translator status would afford me little advantage in navigating Santiago’s byzantine bureaucracy. Renewing my visa would still take the entire morning. And getting an Argentine visa so I could travel with Allende to Buenos Aires for the inauguration of the new Argentine president would take the rest of the day. An early start was imperative.

Taxis had become harder to come by as many of the cab companies had joined the work stoppage led by the Truckers’ Association — a group floated with CIA dollars. Retail merchants, doctors, lawyers and almost everyone more elevated than manual workers and farmers had joined the stoppage. In daily entreaties, they pleaded with the armed forces to do away with the popularly-elected President Allende and restore Chile to Business-As-Usual.

Indeed, Chile had already pitched itself into a dizzying dance of chaos and blood. As Allende’s reforms deepened, as he nationalized the American copper mines and the telephone company, as large rural estates were handed over to their sharecroppers, as wages soared and unions gained a voice in national affairs, as rents were lowered and taxes on the rich increased, the political Right and eventually the Center jettisoned their attachment to the rule of law. Opposition groups fielded chain-swinging thugs. Oil pipelines were dynamited. Industrial production was sabotaged. The wealthy hoarded food and other consumer goods and then complained loudly about the resulting shortages.

Just a week previous to this morning, on September 4, the Chilean Left held its last great public gathering to commemorate the third anniversary of Allende’s election. While the president stood granite-faced on a balcony from early afternoon till late at night, more than half a million Chilean workers marched before him, voicing the nearly unanimous chant: “We want guns! We want guns!” It was a horrible, wrenching moment, one permanently seared in my consciousness. Yes, guns. But what guns? From where? My friends and I walked home that evening with a dark foreboding. The end was surely near.

In the seven days that followed, the Right drew the noose tighter. Commerce and transport ground to a halt. The night before September 11, the transport stoppage had waylaid me and my girlfriend at Melvin’s house. We had gone out as a foursome, wound up snacking at Melvin’s, and got stranded without a way back to my downtown apartment.

My only chance of transportation that morning came from my friends at RadioTaxi 33. Militant revolutionaries, the drivers there had long ago seized the company from its conservative owners and had turned the place into the most efficient cab service in Santiago. And when the drivers weren’t working their shifts, they would volunteer as drivers and messengers for the most powerful workers’ council in Santiago, the Cordon Vicuña McKenna.

After a 45 minute wait on the corner, I became concerned. I went back to the house to call the cab company again but, inexplicably, the phone lines were now permanently busy. I walked back to the corner and eventually was able to flag down a passing cab.

The driver, pale and harried, rolled down the window. “Can you take me downtown?” I asked.

“Downtown?”

“Yeah, to the immigration office,” I answered.

With a classic Chilean understatement, the cabbie replied: “But, sir, there are problems downtown.”

“Problems?”

“Yes, problems,” he said, refusing to be more specific. After all, these were highly polarized times. You never knew who you were talking to. One person’s problem was another person’s liberation. But a sinking feeling in my gut told me the worst was upon us.

Mustering my own diplomatic skills, I asked: “Problems, you say? Problems with men in uniform, you mean?”

“Yes, sir, problems with men in uniform,” the cabbie said. But now, the fear of the future already imprinted on him, he took what he probably knew would be his last foray into freedom for some time and added: “Yes, the fucking fascists are overthrowing the government.”

7:55 a.m., Tuesday September 11

Everyone else in the house was still asleep. I switched on the massive Grundig radio and waited impatiently for the tubes to heat up. As the audio came alive I turned the dial and confirmed the cabbie’s report: virtually every station was playing the same military march.

I stopped the dial on Radio Corporación, the station of the Socialist party. Allende was speaking, a nervous inflection in his voice. His words made material the nightmares that had haunted us for months: “This is the president of the republic speaking from La Moneda Palace. Confirmed reports indicate that a sector of the navy has isolated and occupied the port city of Valparaiso, which means an uprising against the government is under way…Under these circumstances, I call upon the workers of the country to occupy your workplaces…but I urge you to stay calm…At the moment there have been on extraordinary troop movements in the capital…I am here defending the government that represents the will of the people…”

On just about every other radio station a stern-voiced announcer suddenly materialized. By order of the military junta, he said, all stations were immediately to link up to the armed forces network or “they will be bombarded.” The names of the four commanders making up the junta were then read: leading the national police — the carabineros — was a general, César Mendoza, a little-known name; for the air force, Gustavo Leigh; for the navy, Admiral José Merino. But the most important name on the list was Army General Augusto Pinochet. Pinochet, previously Commander of the Central Garrison, had two weeks earlier taken over as Commander-in-Chief, swearing his loyalty to the president he was now trying to overthrow.

Some more Prussian marches. And then another announcement. An ultimatum to Allende. I sat chilled and shaking as I strained to scribble down the text of what a steely voice called Military Communiqué Number 2: “The Moneda Palace must be evacuated before 11 a.m. otherwise it will be attacked by the Chilean air force. The workers must remain in their workplaces and homes as it is strictly prohibited to leave them. If they disobey, they will also be attacked by air and ground forces.”

I sat paralyzed. A few moments later the same dry baritone voice read out Communique Number 3. Again I noted it on a yellow pad. “The population is hereby warned not to let themselves be carried away by incitements to violence from either foreign or national activists. And let the foreign ones know that in this country we do not accept violent attitudes or extreme positions. This should be remembered, as means are adopted for their rapid deportation from the country. Any resistance will be met with the full rigor of military justice.”

Yet another announcement proclaimed a curfew “until further notice.” Anyone found on the streets “will be shot on sight.” I had roused the others in the house. We sat dumbfounded in the chilly living room listening to Radio Magallanes, the Communist party station, boldly resisting the order to broadcast the armed forces network. Over the air, workers were being urged to report to their factories and organize defense committees.

But we knew this was an empty gesture. Those of us who worked in the Allende government knew the sad truth: that in spite of the right-wing chorus that Allende had formed a “parallel army,” no such units existed. Allende had been scrupulous in his commitment to the constitutional, legal and peaceful transition to socialism. The only guns in the country, he vowed, would remain in the hands of the armed forces. Yes, some Socialists and others had formed clandestine militias — but they were operationally risible.

This war was going to be a short, one-sided massacre. And the tragic irony was that those conservative and centrist political forces that for 150 years had defended a constitutional system as long as it served their interests were now rebelling against it. The last man standing in defense of the “bourgeois” constitution would be the Marxist President, AK-47 in hand.

10 a.m., Tuesday September 11

Miraculously, my first attempt to phone the office where I worked in the Moneda Palace went through. Over the sound of crackling gun fire, a secretary, Ximena, told me in tears that she and the others were about to flee the building. My next call was to the U.S. Embassy — up on the 14th floor of an office building diagonally opposite the Moneda. I had had virtually no contact with the embassy and had, in fact, made every effort to steer clear of it. Even my mail was routed to the Canadian Embassy — a government that had shown more sympathy to Allende.

This war was going to be a short, one-sided massacre. And the tragic irony was that those conservative and centrist political forces that for 150 years had defended a constitutional system as long as it served their interests were now rebelling against it.

But I phoned the U.S. Embassy that morning hoping that some safety provisions were being made for resident Americans. I figured it was only a matter of hours before I would be swept up in the military dragnet.

The embassy phone answered on the first ring. An accented English told me that I was speaking with a Chilean employee — always more American than the Americans. When I asked if the embassy had issued any special instructions, my respondent only laughed: “No special orders. Just stay off the streets.” And then with another chuckle she added: “I’m looking out the window now with binoculars. Looks like Mr Allende is finally going to get it.” She hung up.

11 a.m., Tuesday September 11

The leftist Radio Corporación and Radio Portales are off the air. But Salvador Allende’s metallic voice is coming live over Radio Magallanes. Via telephone, from inside the Moneda, with troops and tanks poised outside, with the Air Force Hawker-Hunter jets arming their rockets in readiness, Allende spoke:

This is surely the last opportunity I will have to address you. The air force has bombed the towers of Radio Portales and Corporación. My words are not bitter but they are full of disillusionment. And they will serve as moral sanction for those who have betrayed their oath of loyalty: the soldiers of Chile, the branch commanders…Admiral Merino who has named himself Chief of the Navy. Mr. Mendoza, a slinking general who only yesterday swore his loyalty to the government, has proclaimed himself head of the police…

In the face of these events I can only say this to the workers. I will not resign… With my life I will pay for defending the principles dear to our nation… History cannot be stopped by repression or violence… Surely Radio Magallanes will be silenced and with it my voice. But that’s of no importance. You will continue hearing me as I will always be by your side… At least you will remember me as a man with dignity, a man who was always loyal to you. You must know that, sooner rather than later, the grand avenues on which a free people walk will be open and a better society will be at hand… These are my last words…

I sat stunned and devastated. I can only remember the four of us listening and sobbing for I don’t know how long. The fear was palpable. To go into the streets was to risk arrest and execution. We had no access to any information except what the military broadcast over the radio. The phone lines were now dead.

Everything I learned over the previous two years told me that the Chilean Revolution was now dead.

4 p.m., Tuesday September 11

A non-stop cascade of military communiques: that the Moneda had been bombed, that the Allende government was no longer, that all political activity was banned, that a dawn-to-dusk curfew was in effect, that the citizenry should denounce all “suspicious foreigners.” As that first evening enveloped us I felt as if I were already in prison.

I knew I was a prime target: Allende’s translator, an activist in the radical wing of the Socialist party and a foreigner to boot at a moment when all foreigners were ipso facto suspect. I thought of my apartment and cringed, a downtown high-rise located directly across the street — no more than 20 yards — from the new junta headquarters. Régis Debray, the French writer and radical who had spent time with Che Guevara in Bolivia, had lived in my building when Allende first came to power. Other units were rented to exiled guerrillas from Argentina and Uruguay. The building teemed with the international New Left. One room of my apartment was stocked with the cheap editions of political classics and classic fiction made available under Allende. On my studio desk were copies of the work I had translated for Allende. In my top drawer was my passport, a visa to Cuba where I was scheduled to visit with Allende, and to top it all off, a .22 revolver with a couple of boxes of ammunition. On the floor were two radio transceivers that I was repairing for my buddies at Radio Taxi 33. In short, once the troops broke into my apartment, as they undoubtedly would, a warrant would be issued for a 22-year-old American named Marc Cooper.

Tuesday night to Thursday night, September 11 to 13

Those days were passed in the sort of blur produced by a state of deep shock. All that remains now is a kaleidoscope provided with a semblance of meaning by scraps of hurried, sometimes incoherent notes. I know I didn’t sleep that first night. I imagined Allende riddled and bloodied on his office floor. I could see the Moneda reduced to rubble by rockets and fire. The following morning, an official communique announced that Allende had committed suicide.

I knew I was a prime target: Allende’s translator, an activist in the radical wing of the Socialist party and a foreigner to boot at a moment when all foreigners were ipso facto suspect.

The resumption of Chilean TV. A wavering, black-and-white image — now in the annals of history’s infamy — of General Pinochet sitting ramrod straight in the presidential chair, his arms crossed over his chest, Ray-Ban Wayfarers hiding his dulled eyes, his accomplices in the junta standing beside him.

I thought of the poor neighborhoods and factories, now surrounded by vengeful troops. I wondered about my friends: about Vincente and an American named Vince; Ximena, Jorge, Orlando; about the journalists, the coworkers. How many were already dead? How many would I ever see again? How long would it be before the troops came crashing through Melvin’s door to take me away?

I thought of the celebrations no doubt taking place that night in the lush suburbs of Providencia and Las Condes. I listened to the radio and noted down the congratulatory notes pouring in to Pinochet from the Doctors’ Association, the Lawyers’ Guild, the Chamber of Commerce, the Truckers — all the business sectors that had paved the way for the coup.

On Wednesday a statement from the supreme court chief justice, Enrique Urrutia, affirming the court’s “pleasure” with the military takeover. A terse military statement suspending habeas corpus and announcing a declared state of siege. Military communique number 29 dated September 13: “On this date the government junta has decreed the following: the closure of the National Congress and the vacancy of all its parliamentary seats. Signed, the governing junta of the armed forces and carabineros of Chile.”

I winced at what I knew would be the wave of bloodletting, homicide and torture that was about to wash over Chile. I wondered how the hell I was going to get out alive.

I remember getting up at four in the morning and shaving off my beard. I remember opening my wallet and taking out my union card, my Socialist party membership, my ID from the Moneda and setting them ablaze. Those two days after the coup, Wednesday and Thursday, were marked by the sort of looming madness that I imagine accompanies solitary confinement. We had little food in the house. Melvin — a 30-year-old Bronx-born American — had never told me why he was in Chile. I had always assumed he was ducking a drug possession charge coming out of the ’60s. A fervent Allende supporter, and a fervent anticapitalist, he made his living buying and selling on the black market.

The only food in the house was a freezer full of Eskimo pies, several sacks of onions and a case of Pisco liquor. This odd diet, peppered with fear and haunted by uncertainty, drove me into a feverish, swirling retreat. I could barely talk to my Chilean girlfriend — now my wife — Patricia. I slept, I paced, ate ice cream, read Jim Thompson novels, cried and waited either for the curfew to lift or the door to come crashing down. But mostly we sat and listened to the radio. List after list of the wanted: Allende’s cabinet ministers, party activists, union leaders, prominent and not so prominent exiles had their names read over the air and were ordered to surrender at the Ministry of Defense. How they were expected to step out on the curfew-swept streets without being shot was not explained. As every announcement began, I was sure my name would be next.

10am, Friday September 14

Melvin and his girlfriend have drunk themselves into a stupor. As the radio announces that the curfew will be lifted today for five hours, Patricia and I decide we must leave Melvin’s. She had to check on her family. I had to get my passport out of my apartment and figure a way to safety. Two weeks before the coup my former roommate Carlos Luna, an exiled Argentinian guerilla fighter, had shown up at my apartment with a 9mm automatic. “The shit is coming,” he said, pulling the pistol from his jacket. “When it does, I am getting into the Swedish embassy even if I have to shoot my way in.” But I had no such formidable weapon nor such courage. The military had already announced it had put rings of troops around European embassies. I wondered where Carlos was. Was he dead by now?

My impulse to flight was heightened when, during the break in curfew, a client of Melvin’s, a deli owner, came to the house in his 3-cylinder Citroneta. Well-connected to the military, I took his words at face value when he told me matter of factly, “Cooper, you’re fucked. Your apartment has been raided and they’re out looking for you,” I asked him to drive me somewhere safe. He refused.

A numbing panic gripped me. For the next four hours I could move, but I had nowhere to go. My apartment had been trashed, I was told, my passport seized, my name was on a wanted list, and the streets were full of soldiers and checkpoints. The phone started working again. In what must have been the moment of greatest naivety in my adult life, I thought again of the U.S. Embassy. I had an image in my head from Rossellini’s Rome: open City. I could see the grainy black-and-white footage of Embassy staff cars rushing around the battle-littered streets, their white flags flapping.

I am embarrassed now, years later, to confess that I thought that, given the mounting bloodshed in Chile, the American Embassy on that day would be sending out rescue cars to pick up beleaguered stragglers like myself. I was under no illusions as to where the Embassy was at politically. The Nixon-Kissinger regime had made clear its intention to do away with Allende and it was now three days deep into implementing that goal. But I was deluded enough to think that, in order to avoid the uncomfortable spectacle of American citizens being killed by its new client military dictatorship, the U.S. government might do something to protect us. In this I was entirely wrong.

As the curfew temporarily lifted that Friday I called the U.S. Consulate. Explaining merely that I was an “American student,” that I had done nothing wrong, but that the Chilean Police had raided my apartment and seized my passport, I told the Vice-Consul, Mrs. Tipton, that I needed help. Even as I asked, my heart began to sink. Her husband was the Embassy’s top “political officer,” tied to the darkest aspects of U.S. policy.

The Nixon-Kissinger regime had made clear its intention to do away with Allende and it was now three days deep into implementing that goal.

“Do you have a U.S. driver’s license?” Mrs. Tipton asked me. “Yes.”

“Good,” the Vice-Consul said. “Don’t bother to come in today because we’re about to close. But come in on Monday. Bring your license and $10 and we ‘II expedite you a new passport. Should take about a week, maybe 10 days.”

Stupefied, I argued with her. But to no avail. No special instructions to U.S. citizens were being offered. “Just stay away from shooting and obey the new authorities,” she said. As far as the Embassy was concerned, my predicament was a simple case of a lost passport.

They certainly knew better. But the political calculation had already been made. It was more important to give political support to the new dictatorship than it was to undermine its credibility by suggesting that American citizens needed protection against it.

Noon, Friday September 14

Turned away by the Embassy, I was now desperate. I rummaged through my mental Rolodex and focused on a long shot. An American friend of mine, an Allendista, had told me some months before that a guy named Dennis Allred, who served as the U.S. Embassy’s Student Affairs Counselor, was a decent man, a closet Allende sympathizer who took secret delight in handing out U.S. scholarships to the most radical of Chilean students. True or not it seemed like the only chance I had.

I phoned the Embassy back. No, I was told, Mr. Allred wasn’t in. But, yes, being a fellow American, I could have his home phone number. “Dennis, you don’t know me,” I told him after he answered his phone. “But I’m an American and I’m in trouble. I need … “

“OK,” he said, cutting me short. “I don’t care about the details. If you need a place to stay you’re welcome here. Come now. I’m at Merced 280.”

I thanked him and hung up. Merced 280? That would put him right next door to the heavily guarded U.S. Consulate. Could I get past the troops? Patricia and I hurriedly made a plan. She would catch a bus to her parents’ home but first would swing by my apartment and check its condition. She would call me later at Allred’s. I would walk the seven miles to Allred’s house as I had no ID and buses were being boarded and checked by soldiers.

My clothes were filthy. Melvin, who is 6′ 2″, lent me a pair of pants. I am 5′ 3″. I tucked the bottom of the pants up and pinned them inside with safety pins. He gave me a fresh shirt and I rolled the sleeves up over my wrists. On top of this unlikely outfit I wore my black leather jacket. For three hours I trudged toward Allred’s house, protected only by sunglasses, taking side streets and looking far ahead for any checkpoints.

By 4 o’clock I was on the perimeter of the U.S. Consulate. Neighboring Forestal Park was literally an armed camp. Armored carriers bristled with machine guns and helmeted troops. In front of the Consulate, a few steps from Dennis Allred’s apartment, a company of soldiers lounged on a tank. I could hear my heart beating in my ears. I had no idea what I would tell the soldiers if challenged. I walked straight ahead, my eyes fixed on the door of Allred’s building, my pace steady. Like passing through a time warp, I floated into the building uninterrupted.

A big, red-headed Bostoner, Allred greeted me alone in his luxury apartment. I was so pent up I could hardly talk at first. And then I began to talk too much. “I don’t need to hear the details of your story. You can stay here as long as you have to,”” he said. He then offered me a tumbler full of Old Grandad which I gulped down like water. The booze took the edge off, and I slumped back in the broad padded mahogany chair. I called Patricia at her parents’ house. I was relieved to hear that my apartment had not been raided. She had got in, picked up my passport and a couple hundred dollars, and tossed my .22 and the two boxes of ammo down a garbage chute. She would come and visit me the next day when the curfew was again to be lifted for a short time.

Over a real meal that evening — salad and Kraft macaroni and cheese — Allred told me the news, good and bad. “This apartment theoretically has diplomatic immunity, theoretically Chilean security cannot enter,” he said. “On the other hand, the morning of the coup, the U.S. Embassy took my passport, locked it in a safe, sent me home, and told me they’d call me when I should come back to work. So I don’t know how much protection we really have.” I could only guess that the stories my friend had told me about Allred were true.

She had got in, picked up my passport and a couple hundred dollars, and tossed my .22 and the two boxes of ammo down a garbage chute.

That night, on the convertible bed in his den, the saddest of Portuguese fadas I had fished out of Allred’s record collection drowned the sounds of sporadic gunfire and the rumble of tanks outside my window. With a strong sleeping pill Denis gave me I slept soundly for the first time in almost 100 hours.

6 p.m., Sunday September 16

The word was apparently out on Allred’s generosity. Over the weekend the apartment filled up with other hunted prey. A few had been beaten and bruised by troops who had broken down their doors. Others, like me, had nowhere to go. Still others were there because I had contacted them. Allred had taken the courageous step of abandoning his direct-dial diplomatic phone to us — a luxury in a country where long-distance calls even under optimum circumstances were difficult to make and where now so-called “press-calls” of the sort we were making had to be cleared by a military censor. With Allred’s phone we skipped over those obstacles.

In Allred’s study we set up a mini information clearing house. We called around the city to check on the safety of overlapping networks of friends and co-workers. Once the information was compiled from a mongrel mix of sources — friends, friendly reporters, diplomats, health workers, UN functionaries — we were able to skirt Chilean censorship and pass the information directly on to family, media and human rights groups in the U.S. Painstakingly, we cobbled together lists of those safe, those arrested, and those simply missing. But there was still no way out of Chile. The airports were closed, the embassies sealed. Any foreigner on the street was ipso facto a suspect. Who knew who was on the myriad wanted, arrest and kill-on-sight lists? We already knew the U.S. Embassy was useless.

A friend of mine, a Mexican reporter, called me from his Embassy. Would I be interested in getting on a list that the Mexican Embassy was putting together to be evacuated? “Absolutely,” I answered. I gave him the names of three or four other desperate friends. He told me to sit tight and wait, that word of the flight out could come at any time. I had no choice but to comply.

A few friends who had come to see me at Allred’s told tales of serious resistance, of a regrouping of Allende forces, of guns that were on their way, of former Army General Carlos Prats, forced from office a few weeks before the coup, who was now pulling together a People’s Army. The rumors all sounded wonderful. And we knew they were all false. The Chilean armed forces, the CIA, Nixon, Kissinger, the Chilean business elite had won their victory early that first morning when the Army didn’t divide and when Allende perished inside the Moneda. Now they were just mopping up the rest of us.

Noon, Monday September 17

Word had come that some Americans were missing. David Hathaway had been taken from his apartment. Frank Teruggi was unaccounted for. Sometime that day, our friend Charlie Horman would be seized.

During my time in Chile I had only limited contact with the American expatriate radical community. Some of them had come together in a group called Fuente de Informaci6n Norteamericana (FIN), which struggled to gain a voice as an alternative source of information on Chile to the mainstream media. I had no participation in that project but, for a short time shortly after I arrived in Santiago, I spent a string of Saturday mornings in a “study group” with Frank Teruggi and others. I soon tired of those meetings and what seemed to me at the time their uncritical attachment to the MIR. But I always thought fondly of the spry and witty Teruggi, who was clearly the brightest among his friends.

I had first met Charlie Horman only recently. One afternoon he showed up unannounced at my apartment door and introduced himself as a friend of some of my friends. That was sufficient basis for us, fueled by a couple of liters of rich Chilean red wine, to talk of politics and life deep into the night. We had a few other sporadic lunches and chats.

Now I can only regret that I did not spend more time with Charlie and Frank. I would next see them a decade later and then only as celluloid ghosts conjured up in the Costa-Gavras film “Missing.”

One young American professor rallied us in Allred’s living room and we went as a delegation next door to speak to the U.S. Consul. Enough was enough, we shouted. We wanted the U.S. Embassy to do everything it could to find those who had been arrested. And we wanted protection for ourselves. We wanted the Americans to do what every other diplomatic delegation was doing in Chile — protecting its own citizens from a rampaging, barbarous military. The Consul, Frank Purdy, stood in the hall, blocking access to his office. He spouted the party line: he would look into these matters but there was nothing else to be done that day. The State Department had still issued no specific instructions for Americans in Chile. No special protection was to be extended.

“I recommend you be careful,”” Consul Purdy said. And then he looked us in the eye and came up with a straight-out lie. “The armed forces are restoring order but there’s still a danger of scattered left-wing snipers. Be careful.” With that he shooed us out of the Consulate. In retrospect we made mistakes. Our disgust with our government kept us from making what should have been the next logical move. We should have sat down and occupied the Consulate.

That afternoon, shortly after we slumped back from the meeting with the Consul, the whole apartment shook with a thud. Then another bone-chilling thud. Walking out onto Allred’s second-floor balcony we saw the two tanks that were doing the shelling. Comfortably squatting in the park, they lobbed artillery rounds into the Fine Arts Campus of the University of Chile across the river. That’s how the armed forces of Chile were restoring order.

8 p.m., Tuesday September 18

One week since the coup, and the call came through from the Mexicans. Thanks to the Mexican government I was to be on a flight organized by the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees for the next morning. Apart from a special military aircraft that carried Allende’s widow to Mexico, this would be the first flight allowed out of Chile. There was a catch, of course. I had to be at the distant Sheraton Hotel the next morning at 7:30 sharp. But curfew didn’t lift till 7. It was going to be tight. Nor could I get word to Patricia to meet me to say goodbye. She used a neighbor’s phone and if I called her now, at night, it would be too dangerous to defy the curfew. I’d have to wait till morning to call. This was another low point. The mix of emotion I felt was paralyzing. I was ecstatic at the thought I might get out the next day, but terrified that something might go wrong. I was also deeply depressed, laden with survivor’s guilt: my only prospect for joy was to flee the slaughterhouse of my friends.

7 a.m., Wednesday September 19

The moment the curfew lifted, I called Patricia and asked her to do what she could to meet me at the Sheraton. I hugged Allred goodbye. With only my passport, $200 in cash and the borrowed clothes on my back, I walked past the encampment of soldiers outside Allred’s door. On the corner, a daring taxi driver was ready for the post-curfew fares. When we got to the Sheraton, I began to reach into my pocket to pay him. The cabbie turned around and commenced one of those skilfully coded dialogues.

“Are you a foreigner?” he asked.

“Yes, an American.”

“Have you been living in Chile?” he asked, noting my local accent.

“Yes, for nearly three years.”

“Are you leaving today?”

“Yes. I am leaving.”

“Then,” the cabbie said, “there will be no charge. I want your thoughts about your last moments in Chile to be positive ones.”

Operating on an emotional hair-trigger, I couldn’t answer through my tears. I only nodded.

Inside the Sheraton lobby I was met by UN and Mexican officials. There was to be a motley mix of about 50 of us on this flight. Few of us knew each other. There were some Spanish clergy. Some Mexican teachers. An American researcher black and blue from a beating. A Texas high-school swim team that had had the bad luck to be passing through Santiago on the wrong day. Because Americans were on the flight manifest, American consular officials were there with clipboards in hand. We refused to talk to them.

The mix of emotion I felt was paralyzing. I was ecstatic at the thought I might get out the next day, but terrified that something might go wrong. I was also deeply depressed, laden with survivor’s guilt: my only prospect for joy was to flee the slaughterhouse of my friends.

Just before I boarded the bus to the airport Patricia arrived for a short goodbye — she would arrange to meet me later in the U.S. Under heavily armed military escort we were taken to the Cerrillos military airport. After bureaucratic stalling by the junta’s new immigration officers, who challenged the validity of our UN-secured safe-conduct pass, we were herded onto a corporate 737 owned by LADECO, one of the copper companies nationalized by Allende.

There was an eerie silence as we took off. No one was sure of anyone else on the flight. As we gained altitude, the plane banked around and began to cross the majestic, snow-sparkled Andes en route to Buenos Aires. Twenty minutes into the flight a crackling voice came over the intercom. “Ladies and gentlemen,” the captain announced crisply, “we have just entered Argentine air space.”

The entire plane exploded into yelps of joy and applause. Soon we were all on our feet embracing each other, even the Texas swim team. The Kool-Aid and baloney sandwiches that were served remain to this day the best airplane meal I’ve ever had.

We were greeted in Buenos Aires as heroes even by the immigration police. And that night we marched with 100,000 Argentines to protest the Chilean military dictatorship.

The following week Patricia called me to tell me that on September 22 she went by my apartment and found the front door blown off its hinges, the entire residence sacked by soldiers.

Two months afterwards she came to the U.S. and we have been married ever since. Dennis Allred resigned from the U.S. Foreign Service. Ten years later when I passed through Sweden I found my old guerrilla roommate Carlos Luna running an import-export business with Cuba.

In his final speech on Magallanes Radio, Salvador Allende promised us that one day there would be a “moral punishment” for the crime and treason that killed him and his Chile. We are still waiting.

Of Salvador Allende, his sacrifice and legacy, Gabriel Garcia Marquez lamented: “His greatest virtue was following through, but fate could only grant him that rare and tragic greatness of dying in armed defense of the whole moth-eaten paraphernalia of an execrable system which he proposed abolishing without a shot.”

Extracted from “Pinochet and Me: A Chilean Anti-Memoir” by Marc Cooper, published by Verso Books.

Author’s note: Diplomat Dennis Allred left the foreign service after the coup in Chile. He moved to Chicago and later to Brazil. He died in 1990 at age 45 from alcohol-related diseases.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.