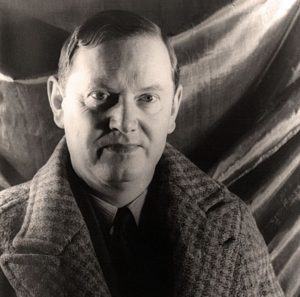

Peter Stothard on Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Hitchens reveals a life in contradictions in "Hitch-22," a brilliant memoir that is at turns comic, self-deflating and sexually frank.

Editor’s note:

When Robert Scheer asked me three years ago to be Books Editor for Truthdig, I was granted sole authority to choose the books and pick the reviewers. Not once has either Scheer or the editors or the staff of Truthdig sought to influence my decisions. That continues to be the case and is emphatically so with regard to today’s review for which I bear sole responsibility. In the world of book reviewing, relationships between reviewers and authors should be disclosed. That would, of course, include any relationship between the assigning editor and the author under review. In the case of today’s book review, readers should know that I have been Christopher Hitchens’ literary representative for the past five years — years which have seen the publication of his “God Is Not Great” and now his memoir, “Hitch-22.” I believed Truthdig readers would be interested in a review by someone of stature and so assigned it, despite the appearance of a conflict of interest that might ordinarily have warranted my recusing myself. Peter Stothard, the former editor of The Times of London and the current editor of the distinguished Times Literary Supplement, is such a reviewer. He is familiar with the English milieu out of which Hitchens emerged, able to expertly parse the literary and political worlds Hitchens has made his own on both sides of the Atlantic over the past 40-odd years. That Stothard was at Oxford at the same time as Hitchens and would later come to know him concerned me less than the intimate advantage he would bring to bear on assessing the book’s literary merit. Whatever his take, pro or con, I was prepared to publish it. These are facts readers will wish to consider and which we wish to declare forthrightly.

— Steve Wasserman

————————

Since there is so little surviving poetry by Christopher Hitchens, consider briefly the following:

I Am the King of China, I’m a Patron of the Prize-Ring. And Every Time My Man’s on Top – I Can Feel My Boxer Rising.

You don’t like it? Well, you may not be the only dissenter. Why am I asking you to read it? Surely, you say, I wouldn’t begin a piece about Susan Sontag or Edward Said with a bawdy invention from their sophomore years. Why does a review of “Hitch-22,” an opportunity for an essay on one of the most vigorously examined political writers in America, require an opening verse quotation about homosexual voyeurism in the Orient? Well, the answer lies here in a wonderful life story, glitteringly told by its author and subject. Stay with me.

First, there is the date of this particular Boxer Rising (circa 1969); and then the place (Oxford, England), and last, the occasion of this fine quatrain, the opportunity taken to contribute to a series of such “King of China” poems, each one written to strictly imposed rules set by a fellow International Socialist, one of the main Trotskyist groups at the time. A good many of what we now know as Frequently Asked Questions About Christopher Hitchens may be answered by a reflection on these themes of metrical respect and perpetual adaptation, principled fixity and mercurial art.

You still don’t get it? OK. True connoisseurs of politics and literature in our times — the readers who most of all will delight in this book — may like now to compare the Hitchens contribution to the poetic model set by James Fenton, that great poet then and now, to which ’60s followers of the “King of China” invitation had to adhere.

I Am the King of China And My Court Is Crammed With Sages. But When I Want a Bit of Bum, I Ring Around the Yellow Pages.

Better, perhaps you’re saying. But, before we get on to the rest of the Hitchens life and its fearless search for the correct side in any argument whatever the consequences, what exactly were those rules? Rules for the poetry, I mean. There were, we are told, only three. The first line, “I Am the King of China,” could not be changed. The second line had to be mildly obscene. And after that almost any sort of seriocomic point could be made. (If anyone still has the Sycamore Press edition from the time, the TLS editor’s library would much like to acquire it.)

These poems, filling less than a page of “Hitch-22,” are a vivid reminder of my own student days (normally an attractive thing once the golden days of one’s youth have had time to separate themselves from the dross). They are a useful reminder too that in the late ’60s and early ’70s there was both a greater seriousness and a greater comedy than you will find in Oxford or any other British city of students and workers today. A vast variety of Trotskyist thought was alive and well practiced alongside styles of life that, except for the introduction of sexually liberated women alongside the men, had changed only patchily since “Brideshead Revisited.” As well as all the fun that was to be had composing “King of China” variations on Magdalen Bridge, there was very much “a war on,” many wars, most notably in faraway but frequently rather close-seeming Vietnam. Washington versus Hanoi is one of a range of potent conflicts in “Hitch-22.” It even features obliquely — but only obliquely since business and pleasure must not be mixed too much — in the third and finest of the stanzas.

I Am the King of China And I Like a Tight Vagina. It Lets Me Show the Things I Know – Like the Prose Style of George Steiner.

Why professor Steiner? In comparison with the placard-waving, picket-line protests of the local industrial estates that engaged much Trotskyist energy at the time, a proper Oxford response to American policy in Southeast Asia was of more significant concern to the famed polymath with an equally famous lack of fear for the heavily laden sentence. In Hitchens’ account here, the great man had challenged over dinner Fenton’s insouciant claim that “there were no great unifying causes left any more, no grand subject of the sort that had sent Auden to Spain or China.” Steiner had snapped back that Vietnam was worth a hard look. Fenton admired Steiner and had a copy of his book of essays “Language and Silence,” including the one titled “Trotsky and the Tragic Imagination.” From that Hitchens “realized that my new chum had suggested to me a possible relationship, which was that of politics to literature but this time beginning at the literary end and not at the ideological one.” It was a relationship that has lasted a lifetime, bringing a powerful purpose to literary criticism on George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh and a rare literary vigor to his political attacks, whatever their target.

|

To see long excerpts from “Hitch-22,” click here. |

“Hitch-22” is the story of its author’s youthful opposition to the Vietnam War, his later more direct involvement in other wars, his perpetual even more direct confrontations, against former comrades as well as more permanent foes in the ideological debates of the past 40 years. But it is also comic, self-deflating and sexually frank, epigrammatic well beyond the pages in which the “King of China” poems occur. Those who want to know the details of a lusty Italian lad’s most likely experience in the shared embrace of Gore Vidal and Tom Driberg will find their every desire met. In the George W. Bush years Hitchens’ support of the administration’s policy toward Iraq spawned a minor industry of questioning as to how so dedicated a man of the left should become so potent a spokesman for the neoconservative cause. For those who find these worthy works somewhat hard-going, for those whose early study of Trotsky was either nugatory or unleavened by Steiner, this book is an easier, gentler way. Vietnam is the last war described in “Hitch-22” where Hitchens was not himself present. In those early days he merely joined every demonstration he could reach against the British Labour government’s support for the “hideous” President Lyndon Johnson. Probably the first evening that I ever saw him myself (this is the appropriate time, I think, to declare that we have become closer friends since) was when in 1970 he organized the shouting of “Murderer!” and the hanging of a noose in the face of the then Labour foreign secretary, Michael Stewart, at the Oxford Union. He was the star of Balliol College, a nest of Marxists as those of us at Trinity next door liked to see it. He was an actor in the student protests of the age while I merely watched from the stalls, and only even then when the fracas was likely to be especially watchable or when I couldn’t get out of the way. The night of the noose was in the first of those categories although, once inside the Union’s Victorian hall on that occasion, it was not that easy to get out of trouble’s way either.

As soon as the geographical restrictions of Oxford were over, our author began a career of journalism and public commentary that left the “secondhand” far behind. Getting close to the action became a necessity, talking directly to the actors, applying an Oxford empiricism to the application of all political ideals, especially Balliol’s and his own. Thus readers of “Hitch-22” will find themselves in Belfast and Bosnia and Buenos Aires and Babylon, not always at the height of a horror story (he is not a TV anchor or a big-foot newsman) but at times when the key actors can be found, can be asked the questions they would rather not be asked and subjected to all the searching they can normally avoid. The author’s ideal for himself is to judge by the stare straightest into the face. Whether the targets are some of Britain and North America’s overrated intellectuals, the “academics of Oz,” or some of the nastiest South American torture specialists that most would never want to meet, he much prefers bad arguments to be directly heard before they are exposed and abused.

Whence did this character come? There is no point in a book of this kind unless that question is addressed. One insistent theme — from the very start and, since this is an autobiography, it is the very start — is the search for some sort of point in living a life at all, let alone writing about it. For Hitchens’ father, affectionately if distantly nicknamed “the Commander,” the end of the Second World War was more or less the end of purpose, a time of service in the Royal Navy crowned by his part at Christmas 1943 in the sinking of the Scharnhorst, “a better day’s work than any I have ever done,” as his son concedes. His paternal aunt, Ena, landed in Normandy as a nurse after D-Day, and continued all the way to Germany, “another excellent day’s work.” Fighting Fascism in its various forms is seen as an absolutely secure purpose for life, even if identifying it is easier at some times than at others. After the war the Commander’s “Tory sensibility” took over, the kind that his son came permanently to oppose, a defeatism based on the sad experience that Britain had been defeated even as it won its war; and that future wars, even for the Falkland Islands, which he had known and visited in his naval days were no longer worth the trouble. The son disagreed with his father on the Falklands issue in 1982 as on so much else, supporting Margaret Thatcher’s ambitions over Gen. Galtieri’s, even as so many of his sometime British comrades chose the other side.

For Hitchens’ mother, Yvonne, life was a more personal defeat, a story of dull home life after the exotica of the navy’s foreign postings, small setbacks in her desire for some small freedoms (each one movingly portrayed by her son) and finally a shared suicide beside a clinically depressed lover in an Athens hotel room, photographed by the Greek police for evidence, visited by her son in an investigative homage. He is avowedly and movingly his mother’s son. She was “the cream in the coffee, the gin in the Campari, the offer of wine or champagne instead of beer, the laugh in the face of bores and purse-mouths and skinflints, the insurance against bigots and prudes.” She was also partly Jewish, and keen to hide that fact, having “wanted to ‘pass’ as English after noticing some slight unpleasantness being visited on my grandmother who, in the 1930s, toiled in the millinery business.” This was a concealment that caused some trouble between them at the time of the 1973 conflict between Israel and its neighbors, “what some call the Yom Kippur War and some the Ramadan War.” On this the final subject that they shared on the telephone, that of her moving to Israel and “taking someone else’s bleeding holy land on top of her other troubles,” he writes that “I would give a very great deal to be able to start that conversation over again.” Forty years on, she inspires a coda on the question of self-slaughter, the 14 suicides in Shakespeare, the fears of William Styron, the martyrdom of Jan Palach in protest at the Soviet invasion of Prague, a self-immolation which once Hitchens had praised but now he praises less. Today he has had “every chance to be sickened by the very idea of martyrdom,” an act which now joins the lists of other horrors of religion, not least the great Jewish Masada itself, which is misunderstood by his friend, Al Alvarez, as well as by almost all other writers, being not a mass suicide decision at all but a fanatical extremist excess. As for Yvonne, she may not herself “have needed or wanted to die but she needed and wanted someone who did need and want to die.”

In its pages of more public life, the text is studded with an array of names that have recurred, often in unexpected ways, over the years — from Martin Amis to Abu Nidal, Salman Rushdie to Paul Wolfowitz, Jorge Luis Borges on the etymology of a “trafficker in cunt,” Philip Larkin on the phrase Yank bags, Jessica Mitford on being “non-speakers” with her sister, Diana, “since Munich,” the courageous Jacobo Timerman and his son. Hitchens and Bill Clinton share a student role as the “tethered goat” for a pair of Sapphic young Oxford friends who wish to attract fellow females into their den. Later the two take notoriously more divergent parts in the president’s impeachment over the Monica Lewinsky affair. The former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw takes issue with Hitchens over the noose for his predecessor at Oxford, arguing as a student union leader at the time that protection of free speech was the higher virtue. But when we reach the 2003 war in Iraq, they are both on the same side, Straw being a rather reluctant fighter in the neoconservative cause, our author characteristically more ferocious in his support.

Hitchens’ pugnacity in defense of George W. Bush and Tony Blair has severely tested his admirers in the past seven years. In his chapter “Mesopotamia from Both Sides,” he recounts how his once favorable view of Saddam Hussein as an “up-and-coming secular socialist” and of Iraq in 1976 as a “progressive model for the rest of the Middle East” was reversed only in a long and “painful” process. His first contacts were a Baathist minder who liked to play Gwendolyn” in domestic performances of “The Importance of Being Earnest.” Hitchens approved the regime’s early recognition of Kurdish identity and rejection of Islamic rhetoric — while noting and attempting to combat the oppression of communists. The invasion of Kuwait was one milestone on the painful road out, the chemical attacks on the Kurds another; but he concedes that his opposition to the first President Bush’s role in aiding a Central American dictatorship with illegal funds from Iran remained an obstacle to going further. Marxist colleagues told him that they had all to choose between a course of anti-imperialism, tolerating a Saddam who would at least help the Palestinian cause a little, and anti-fascism, rejecting Saddam for his cruelty, aggression and intolerance.

Hitchens came to decide that this was no choice: With George H.W. Bush and his Kuwaiti and Saudi friends “you could have both imperialism and fascism.” Direct experience of the horrors of the Halabja gas attacks on the communist-sympathizing Kurds was the first decisive move toward the creation of a tiny group of “conspirators” that came to play so critical a part in promoting George W. Bush’s war in 2003. To a man of the highest education in the old left, “the idea of ‘Reds for Bush’ might seem incongruous but it was a very great deal more wholesome than ‘Pacifists for Saddam.’ ” Keeping contact with the country when others in the Clinton years looked elsewhere, he began to extend his links with others who recognized “the radical evil” of Saddam’s rule, liberals and neoconservatives who redefined themselves in relation to the new circumstances especially after 9/11, a Trotskyist architecture critic, an aide to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a Welsh Labour MP, Kurdish and Swedish diplomats, the veteran Washington infighter, Paul Wolfowitz, and the man who has since become “so well hosed with bile and spittle,” the Iraqi exile and passer of the Hitchens “acid test” for Trotskyist comprehension, Ahmad Chalaby.

In this book Hitchens has remained characteristically loyal to these men and their ideals, even as his former allies on the left have raised their eyebrows, curled their lips and worse. He does not spend long on the failings and failures of the invasion; still less does he defend every aspect, becoming by his own admission “coarsened and sickened by the degeneration of the struggle” and arguing that there are limits, in the case of a political and literary commentator, quite extensive limits, to a writer’s knowledge of civil and military logistics. He ends instead characteristically with a single instance, of a California soldier, killed in Iraq, whose decision to fight had, according to his family, been “deeply influenced” by the moral case for war he had learned from “writings by the author and columnist, Christopher Hitchens.” He attends Mark Daily’s funeral service, meets his family and ends with the nobility observed by this single soldier, fighting as had Orwell in the Spanish Civil War for aims which seemed “fly-blown” to the old and cynical but were fresh to all who found them for the first time and must always be kept fresh.

|

Peter Stothard, editor of the (London) Times Literary Supplement, is the author of “On the Spartacus Road, A Journey Through Ancient Italy,” published in the United States by Overlook Press. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.