Penguins Feel Climate Change’s Impacts

Fewer penguin chicks that hatch in a colony in Argentina reach maturity, scientists found -- and they say climate change is the culprit.

By Tim Radford, Climate News NetworkThis piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

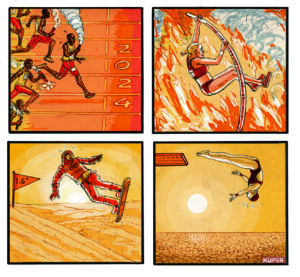

LONDON — Climate change is bad for penguin chicks. If rain doesn’t soak their feathers and kill them with cold, then extremes of heat could finish them off with hyperthermia.

Over a 27-year research project in the world’s largest colony of Magellanic penguins, on the arid Argentine coast, researchers have seen a greater number of deaths directly attributable to climate change.

“We’re going to see years where almost no chicks survive if climate change makes storms bigger and more frequent during vulnerable times of the breeding season”, says Ginger Rebstock, who, with Dee Boersma, reports on the state of penguin survival in the Public Library of Science journal PLOS One.

The two scientists, biologists from the University of Washington, Seattle in the US, believe starvation and weather are going to make life harder for the offspring of the 200,000 pairs of penguins that breed each year at Punta Tombo, on Argentina’s Atlantic coast.

The number of storms during the first two weeks of December – when all the chicks are less than 25 days old and their downy coats are not yet waterproof – has increased between 1983 and 2010.

Every new chick is at hazard: over the span of study, the researchers calculate that 65% of chicks do not survive, 40% of them die by starvation. But climate change has begun to offer new dangers.

Some years up to half of all chicks die because of the weather. Punta Tombo is historically an arid region. In the last 50 years, the scientists report, rainfall has increased. The number of wet days has increased, the number of consecutive wet days has increased and the level of rainfall during those days has continued to increase.

Air temperatures changed too. The minimum temperatures decreased by up to 3°C and the number of these colder days increased. Storms, too, make it more difficult for foraging parents to gather enough food to feed their chicks.

Sea ice changes

“Starving chicks are more likely to die in a storm”, says Prof Boersma. “There may not be much we can do to mitigate climate change, but steps could be taken to make sure the Earth’s largest colony of Magellanic penguins have enough to eat by creating a marine protected reserve, with regulations on fishing, where penguins forage while raising small chicks.”

Further south, extreme weather is beginning to make life difficult for the Adélie penguins of Ross Island in Antarctica. Amélie Lescroël from the CNRS in France and colleagues report in the same edition of PLOS One that abnormal sea ice conditions reduce access to food.

Antarctic penguins are of course adapted to sea ice: it is their preferred habitat. But they must respond to short and long term changes in ice levels. For 13 years, scientists have monitored the feeding success of the Ross Island colony and observed that the birds could cope in those seasons when there was less sea ice.

But climate change in Antarctica, too, creates new problems for the birds and limits their foraging efficiency.

“Our work shows that Adélie penguins could cope with less sea ice around their summer breeding grounds”, said Dr Lescroël. “However, we also showed that extreme environmental events, such as the calving of giant icebergs, can dramatically modify the relationship between Adélie penguins and sea ice.”

If the frequency of such extreme events increases, then it will become hard to predict how penguin populations will get by, she thinks.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.