Oscar López Rivera and the Struggle for Puerto Rico’s Freedom

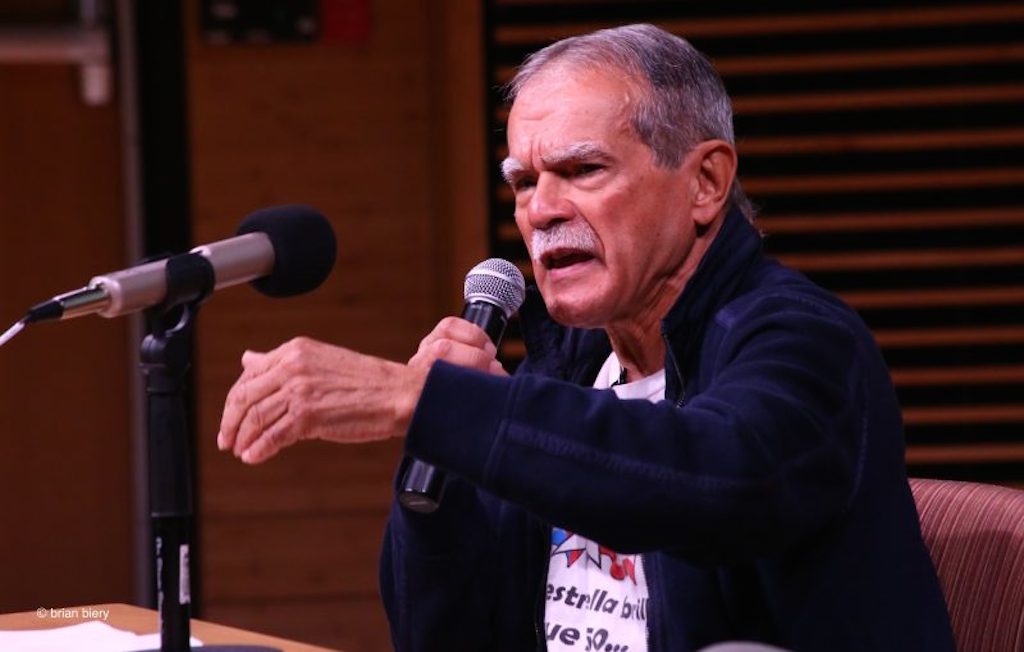

Released from prison in 2017 after 35 years, the Puerto Rican nationalist and activist explains why he’s optimistic about the future and independence for the island. Oscar López Rivera speaking at Pasadena City College in February. (Brian Biery)

Oscar López Rivera speaking at Pasadena City College in February. (Brian Biery)

“The only thing that is impossible in this world is that which doesn’t get done, and every problem created by man has a solution. If we want a better world, we will have to fight for it; it’s not going to be given to us.”

—Oscar López Rivera, Pasadena City College, Feb. 7, 2018

Oscar López Rivera has been called the Nelson Mandela of Puerto Rico.

Like the South African icon, López Rivera was imprisoned for his anti-colonial activism and spent more than 35 years in prison—even longer than Mandela did. In May 2017, López Rivera was freed from the Terre Haute federal penitentiary in Indiana and less than a year later embarked on a nationwide speaking tour. During his visit to Pasadena City College (PCC) this week, I spoke with the man who became one of the longest serving political prisoners in the world. His small stature and modest clothing (he sported a worn white T-shirt, faded khakis and a set of surprisingly bright orange Nike sneakers) belied his reputation as a figure whom many consider a heroic freedom fighter.

“I was not prepared at all to receive the news,” he said about discovering that President Barack Obama, as one of his last acts in office, had commuted López Rivera’s 70-year sentence in January 2017. “I’m very grateful to Obama,” he told the audience, “but the force behind the decision were the people who love freedom and justice in this world.” He was referring to people such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Pope Francis, Sen. Bernie Sanders, playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda and the many activists and organizations that advocated for his release over the years.

López Rivera was born and raised in Puerto Rico and was drafted into the U.S. military as a young man. He spent a year fighting in the Vietnam War, an experience that changed his perception of his homeland: When he returned, he viewed the island as an occupied land, one that had been colonized first by Spain and then by the United States. He joined the underground militant organization known as Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional Puertorriqueña (FALN), which targeted military bases and other symbols of American imperialism. López Rivera has denied involvement in any actions that hurt people and was, in fact, convicted of “seditious conspiracy” rather than a specific violent crime against a person or persons. A lengthy profile of him in Waging Nonviolence last year attempted to set the record straight about his views on violence and how he has repeatedly pledged not to “engage in nor advocate acts of violence” and expressed “his personal devotion to the sanctity of life.”

Still, some conservatives have painted López Rivera as a “terrorist.” When an audience member at the PCC event raised the issue of López Rivera’s role in FALN, the 75-year-old took great umbrage, responding, “When we talk about bombings and things of that nature, people obviate facts.” He also cited the United States’ racist past. “There were organizations that lynched people and they got away with the lynching,” he said. “The racists can get away with things that others cannot.” López Rivera also invoked the violence of the U.S. state through his own experience of being “drafted into the United States Army and taught to kill.”

López Rivera’s commitment to fighting for social justice remains strong after all these years. “The only way that we can really be effective is to look at what we do,” he told me, “and as long as we know that we’re serving just and noble causes, not to stop, not to allow the whole system of criminalization to take us down.”

When I asked what first inspired him to be politically active, and what keeps him so today, he told me the story of how he heard the voice of Puerto Rican independence activist Lolita Lebron on a tape as a young boy. López Rivera remembers hearing the strong voice of a woman he later discovered was Lebron saying, “I came to Washington not to kill anyone but to give my life for Puerto Rico.”

“She was an inspiration to me from that moment until the day that she died, and she still is in my thoughts and my heart,” he said.

Two years after Puerto Rico was classified as a commonwealth of the United States in 1952, Lebron and other Puerto Rican nationalists famously fired pistols inside the U.S. Capitol building while members of the House of Representatives were meeting. Like López Rivera, Lebron served decades in prison for her actions. She was released by President Jimmy Carter after serving 25 years and later in her life embraced nonviolent civil disobedience as a political tool.

Like Lebron, López Rivera is hailed as a hero despite the controversy over his actions as a young member of FALN. Over the course of his imprisonment, he became a symbol of resistance to people around the world, uniting diverse Puerto Ricans from many parts of the social and political spectrum around his release. “Everything that had stopped us in the past from coming together came together around the campaign to [free] me,” he said.

López Rivera returned to Puerto Rico just months before the island was devastated by Hurricane Maria. Reports continue to emerge of the shocking way in which private contracts were handed out to inexperienced and severely understaffed American companies to provide aid. The latest example is a report of a one-person company hired to deliver 30 million meals to Puerto Ricans for $156 million. Only 50,000 meals were ultimately delivered, and even those lacked the heating pouches they were supposed to come with. But as López Rivera told me, the privatization model is nothing new in Puerto Rico, and the only way for the island to recover its economy is to be free of U.S. colonial rule.

The independence movement in Puerto Rico has been wracked by infighting for many years, and part of López Rivera’s goal with his newfound freedom is to help unify various parts of the movement. “The idea would be to create a big, big tent where every Puerto Rican who loves Puerto Rico can come in and say, ‘We want Puerto Rico to be decolonized,’” he explained. “We’re organizing town hall meetings—we call them ‘conversatorios’—and the reception has been very, very good.”

Already, López Rivera has noticed a shift in the political leanings of the population since the hurricane. According to him, the poorest residents of the island have not traditionally been pro-independence, “since they rely on food stamps” and other U.S. government assistance and have been fearful of losing benefits. But after Maria hit the island, López Rivera found that there was greater receptivity to the idea of economic self-sufficiency and self-determination. He shared that cooperatives are emerging to a greater extent in Puerto Rico—partly out of necessity given the dismal state of post-hurricane relief from the U.S. government—and there is even a renewed interest in urban gardening, especially among young people.

López Rivera’s optimism is surprising, not just because of the terrible state of post-hurricane Puerto Rico, but also because he spent so many decades behind bars, including years in solitary confinement. One of the ways in which he preserved his sanity was through art. An accomplished artist, he shared with me why he took up painting and how it benefited him and others: “In 1990 I realized I was going to be held in solitary confinement for a long period of time,” he said. Knowing that he “was going to be subjected to a monochromatic cell for a long time,” he “decided to start using colors, and little by little I fell in love with painting.” Not only did art become a form of therapy, but art sales also became a way for López Rivera and several other Puerto Rican political prisoners to finance the external campaigns for their freedom.

Age and a lengthy incarceration have not slowed down López Rivera, who remains ambitious about achieving independence for his homeland even as he rediscovers his own freedom after so long. He left me with a singular piece of advice that summed up his zeal:

“Life is to be celebrated. Don’t forget that.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.