One Year On, What We’ve Learned From #BlackLivesMatter

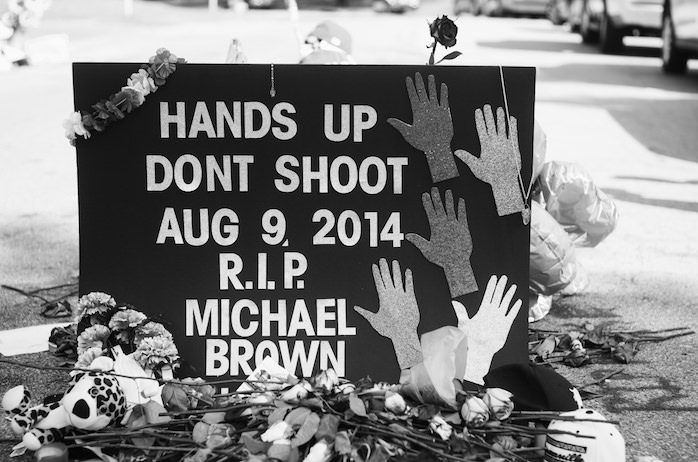

The police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., a year ago launched the Black Lives Matter movement. But officer-involved shootings seem only to have accelerated. Wikimedia

Wikimedia

Sunday is the one-year anniversary of the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and effectively the anniversary of the #blacklivesmatter movement. So what have we learned in the past year? We have learned that more blacks are dying at the hands of police and in police custody and at a faster rate than any of us could have known. Literally, we could not have known how many and how often black people were dying in these circumstances because there is no national database of officer-involved killings and deaths in custody.

We have also learned that the deaths are so frequent that we may not be able to keep up with them all. “Did you hear about the black man killed by police when he was running away?” You mean Michael Brown last year? “No, I mean Jonathan Ferrell two years ago!” But we only heard about it last week as the case went to trial. We only heard about it because Michael Brown’s shooting and the #blacklivesmatter movement have raised the consciousness of a nation.

This raised consciousness has resulted in a 14 percent increase just in the last year in Americans who feel that the nation needs to make more changes to bring equal rights to blacks. According to a Washington Post poll, fully 60 percent now feel such changes need to continue. Does that mean 60 percent believe that body cameras should be worn by all police officers? Or that 60 percent believe the Confederate flag should come down? Increasingly, these beliefs represent a consensus of the country. However, that still leaves 40 percent – 40 percent who support Darren Wilson (the officer who shot Michael Brown), 40 percent who support George Zimmerman (a Florida neighborhood watch volunteer who shot Trayvon Martin), and it leaves 100 percent of the Republican candidates for president who don’t believe #blacklivesmatter.

And that affirmation may be a major wedge issue in the presidential contest next year. The Democratic candidates have already been put on notice by activists that nothing less than an unqualified exhortation will suffice. The palliative “All lives matter” fails to recognize the moment that we are in, a moment ushered in by the killing of Michael Brown and all the others whom the movement represents.

In these brief 12 months we have begun to see a major shift in the way police departments and prosecutors are responding to police shootings. Officers are being fired, arrested and charged at a head-snapping pace — but only when there is incontrovertible video evidence laying out a clear picture of the incident. On Sept. 4, a South Carolina highway patrolman shot unarmed black motorist Levar Jones. Jones pulled into a gas station and got out of his car when the officer stopped him for not wearing a seat belt. When the officer instructed him to produce his driver’s license, Jones reached for it inside the car. The officer opened fire. Jones staggered backward, with his hands up, while the officer continued to shoot at him, striking him in the hip and injuring him.

So often it is said that if blacks would simply follow officers’ commands, there would be no reason for lethal force. The Jones case is a perfect example of how untrue that assumption is. The irony is that while witnesses disagree on whether Michael Brown had his hands up in the surrender gesture, Jones appears clearly on the video to be doing exactly that, to no avail. This makes the claims of witnesses who said Brown had his hands up at least plausible if not verifiable. The highway patrolman in the Jones case was fired and is being prosecuted by the district attorney.

On April 4, Walter Scott, another unarmed black man, also running away (as was Michael Brown), was shot in the back by an officer in North Charleston, S.C., after a scuffle. But this killing was captured on video by a witness, providing evidence that resulted in murder charges against the officer who otherwise might not have been charged at all.

On April 12, Freddie Gray was arrested in West Baltimore. Some of his arrest was captured on video, up to the point when he was put in a police van for what should have been a five-minute ride to the station. After a 45-minute “rough ride,” he was unconscious when the van finally arrived. Gray never came to and died a week later at the hospital.

Sandra Bland died July 13 in custody in her cell at the Waller County, Texas, jail. Her death was not caught on videotape, but her arrest was. The dashcam of the state trooper’s vehicle showed the exchange at the car after he pulled her over for failing to signal a lane change. He seemed to take every opportunity to provoke and escalate the encounter. When Bland refused to put out her cigarette, the trooper pulled her out of her car and arrested her, even though he had stopped her just to give her a warning. Three days later she was dead.

On July 19, a University of Cincinnati police officer shot and killed Samuel DuBose, an unarmed black man, after stopping him for the lack of a front license plate. The officer started to open the door and ordered DuBose out of the car when he failed to produce a driver’s license. When DuBose turned on the ignition, the officer pulled his gun and shot him in the head. The car rolled to the other side of the street, with the officer in pursuit on foot. He later claimed that the car was dragging him down the street and he feared for his life. Less than two weeks later, the officer was indicted for murder.

How did we get from the months of waiting for a grand jury in St. Louis to announce its non-indictment in Michael Brown’s death to the almost immediate indictment of the University of Cincinnati officer? The main lesson we have learned from Ferguson and all the events in its wake is that transparency covers a multitude of sins. It may seem counterintuitive, but time and again we have seen that when the authorities are transparent about the processes and procedures around these killings, the public is quite willing to work within the grievance structures made available and limits of their constitutional rights. But when obfuscation, denial and cover-up occur, the demands of the people are made by any means necessary. In Ferguson and Baltimore, the concealment, cover-up and stonewalling by police departments led to what some called rioting and to violence by those in the community who felt no other response was adequate to address the violence unleashed by police on the residents of their community.

For those of us with any perspective, the public reactions in Baltimore, and certainly Ferguson, barely qualify for the label “riot.” Aug. 11 will be the 50th anniversary of the Watts riot in Los Angeles. A damaged convenience store in Ferguson and CVS in Baltimore have become the symbols of the recent events. In L.A. in 1965, 34 people died and 118 suffered gunshot wounds. Most of those who died were killed by the L.A. Police Department and the National Guard. Over $40 million in damage was done. In 1992 in L.A., after four police officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King, more than 60 people were killed, thousands were arrested and over a billion dollars in damage occurred over hundreds of square miles.

The one thing that these events have in common? They all started with a minor traffic violation or petty crime alleged by white officers against a black person. Michael Brown: jaywalking. Eric Garner: selling untaxed cigarettes. Sandra Bland: failure to use a turn signal. Samuel DuBose: lack of a front license plate (not even required in many states). Freddie Gray: running from police. Walter Scott: broken tail light. Jonathan Ferrell: being mistaken for a burglar when seeking help after a car crash. Levar Jones: not wearing a seat belt.

These are just a sampling of the best-known cases from the past year. There are likely scores or hundreds of others that, without the benefit of video, we will never know about but that are buried in the crime statistics (though still none on officer-involved shootings) from rural southern hamlets on through to the annals of the New York City Police Department’s “Stop and Frisk” program.

Michael Brown was not the first unarmed black man killed by police and he will not be the last — at least until #blacklivesmatter actually matters to everyone.

Show your support for Truthdig’s independent journalism and donate today.

Rev. Shockley: Support Bringing Truth to a Post-Truth Era from Truthdig on Vimeo.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.