On Fire I Will Burn

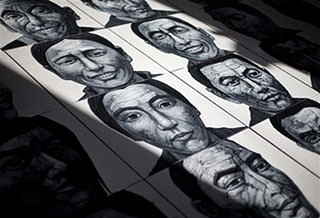

Beijing is wiping out indigenous culture on the Tibetan Plateau. In protest, 98 people have set themselves on fire since 2009.

By Bhuchung D. SonamTenzin Wangmo was born in 1991 and joined Dechen Choekhorling nunnery in childhood. On Oct. 17, 2011, she walked to Sumdo Bridge in Ngaba in northeastern Tibet and set herself on fire. With this she became the first female Tibetan self-immolator and as the flames engulfed her body, Wangmo called out for an end to religious repression, and the Dalai Lama’s return. She was 20. Ninety-eight people have set themselves on fire since 2009. Their average age is 25.

Beijing’s policies over Tibet’s religion are based on fear and distrust, since Buddhism and its cultural influence bind Tibetans and give them a sense of national identity. The Chinese Communists’ attacks on Buddhism date back to the Long March of 1935, when Red soldiers walking through eastern Tibet destroyed monasteries and confiscated grain stores. After China’s invasion of Tibet in 1959, Beijing imposed one disastrous policy after another, culminating in the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), during which more than 90 percent of Tibet’s monasteries and nunneries, along with their ancient scriptures, were destroyed. This is akin to wiping out all of the universities in the United States, because Tibet’s monasteries functioned as centers of learning and education.

Since the 2000s, Beijing has relaunched and intensified the “Patriotic Re-Education Campaign” throughout the Tibetan Plateau. This is enforced particularly harshly in monasteries and nunneries where monks and nuns are required to study and take written tests to prove that they oppose separatism and to endorse the official line that the Dalai Lama is destroying “the unity of the Motherland.” Furthermore, the government distributed millions of red flags and portraits of Mao and other Chinese leaders and made it mandatory for monasteries to display them in place of photographs of the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan religious leaders.

In July 2007, the People’s Republic of China’s State Religious Affairs Bureau issued Order No. 5, a set of regulations for the atheist Communist Party to control the reincarnations of Tibetan lamas. This was the ultimate interference in Tibetan spiritual practice and a gross violation of the freedom of religion as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and China’s constitution. Reincarnation is a unique system of successive rebirths of spiritual masters in Tibetan Buddhism. This uninterrupted lineage is essential to transmit the accumulated wisdom of the previous lama to his new incarnation.

For spiritual practitioners such as Wangmo, Buddhism constitutes the very essence of their lives. They have left behind their families and renounced the world to pursue a life of spiritual training and accomplishment. This systematic attack on Buddhism is a fundamental transgression into this sacred realm. The situation is exacerbated by the lack of any civil channels to air their pain. Monks and nuns who sacrifice themselves on fire often feel they have no alternative means to demonstrate their suffering and seek redress.

However, Beijing’s restrictions on religion are not the lone cause of Tibetan self-immolations.

On March 3, 2012, Tsering Kyi set herself on fire in Machu, a town on the banks of the Machu River in eastern Tibet. Kyi was born to a small nomadic family and started school at the age of 10. That March day, she emerged from a public toilet engulfed in flames, her fist raised defiantly. As she was running toward the local market, Chinese vegetable vendors blocked her path and pelted stones at her burning body. Kyi died on the spot. She was 19.

Kyi’s self-immolation was inspired by two of Beijing’s most insidious policies to destroy Tibetan identity — forcing nomads to permanently settle down, and imposing Chinese as the medium of instruction in Tibetan schools.

Resettlement of nomads started in 1956, when Zhu De, commander in chief of the People’s Liberation Army, ordered nomads to settle “to facilitate socialist transformation.” However, the permanent settlement of nomads began in earnest in the 1990s. Claiming environmental protection as the rationale for fencing off their pastureland and settling nomads, Beijing imposed a ban on grazing and claimed the nomads’ “primitive” and “unscientific” way of life had resulted in soil degradation in pastoral regions.

An estimated 2.5 million nomads inhabit the Tibetan Plateau. For centuries they have skillfully managed their livestock and nurtured the land while adapting to the realities of the plateau’s fragile ecosystem. The current crisis in pastoral regions actually stems from Beijing’s earlier policies, such as compulsory collectivization, imposition of soaring production quotas and collectivized herding.

The authorities have been implementing large-scale human resettlement, land confiscation and fencing policies for nomadic communities since 2002. These radical rules require the nomads to sell their livestock to Chinese-built slaughterhouses and then force them into concrete-box colonies at inhospitable locations — such as disused prison sites — where there is neither drinking water nor electricity.

Kyi was from one of thousands of families affected by these policies. Although she was still a child, her nomadic family, which traditionally moved between summer and winter pastures, was forced to settle on a small plot of land. Barbed wire surrounded pastures, and so the ancient ways for herds to roam freely over the grasslands ended. Consequently, the knowledge accumulated over 9,000 years of Tibet’s mobile civilization is today rendered useless.

For a new generation of Tibetans such as Kyi, the dilemma does not end there. The loss of their traditional way of life is made worse by an uncertain future. Kyi was a bright student and an avid reader. However, her desire to excel in Tibetan language and culture also was coming to an end. In October 2010, the Chinese authorities in Amdo (Qinghai, in Chinese) passed a law to replace Tibetan with Chinese as the mode of instruction at all educational institutions. In response, more than 3,000 Tibetans, including Kyi, took to the streets to demand freedom for Tibet and the right to their own language. In fact, her school became the center of this activism. The authorities cracked down swiftly. Hundreds were detained and the headmaster of Kyi’s school was fired.For Tibetans, language is the heart of their culture and identity. Like water, it sustains Tibet as a country and Tibetans as a people; like air, it supplies Tibet’s religion, music, literature and history. Banning the Tibetan language is meant to finally destroy the region’s culture and identity.

A leaked official Chinese document issued in May 2011 focuses on the need to “strengthen education in dialectical materialism and historical materialism in classes on ideological and political theories.” In language resembling that of the Cold War era, the document further asks cadres to “deepen the development of resources for political ideological education in various classes. …” Hence, Beijing’s fundamental education policy in Tibet has been to win over the loyalty of generations of Tibetans through mandatory education in Chinese, while deliberately sidelining the Tibetan language. This is highlighted in a recent appeal letter to China’s new leader, Communist Party Secretary General Xi Jinping, by members of the international Tibetan studies community. They wrote: “We know the value of Tibet’s civilization and we regret that the Tibetan language, which is its fundamental support, is seemingly marginalized and devalued. …”

As a child growing up in a nomadic community, Kyi experienced the resettlement of her nomadic family firsthand; as a student, she discovered that her language would no longer be taught in school. Deprived of everything that she knew — and feeling that there were no other avenues to express her dissent — Kyi chose the last resort. Two months before she set herself on fire, Kyi told a relative that “We should do something — life is meaningless if we don’t do something for Tibet.”

And then on May 27, 2012, two young men set themselves on fire in front of Jokhang. This holiest temple in Tibet, located in the heart of the city of Lhasa, is today filled with police and paramilitary forces. Dorjee Tseten, 19, was a chef in a small restaurant called Nyima Ling and his friend Dhargye, 24, was a cashier at the same eatery. As a knee-jerk reaction, Beijing unleashed more paramilitary forces into the city and hundreds of eastern Tibetans who had made their homes in Lhasa were arbitrarily expelled.

In August 2012, three months after Tseten’s and Dhargye’s self-immolations, state-run CCTV called Lhasa the “happiest city” in China. But as the officials were crowning Lhasa, a large contingent of security forces was setting up checkpoints and scanning every Tibetan coming into the city. Tibetans from other regions wanting to live there are required to obtain special permits, unlike Chinese arrivals.

The Han natives flooding the city bring with them their alien habits and language. Woeser, a Tibetan author based in Beijing, writes that the danger for Tibet may not be China’s military threat, but rather the cultural invasion. “Because the imperialist cultural invasion in Tibet can be observed in every little detail,” she writes, “the impact and influence of these changes leave you with no option but to give up or adapt. The eventual consequence is likely to be that there is no longer a ‘you’ left. … ‘You’ will vanish in the end.”

The fundamental challenge for China is not to identify and foil who might be the next self-immolator in which town, village or nomadic tent, but to recognize that many on the plateau are against Beijing’s rule over Tibet, and that every Tibetan could potentially set him or herself on fire. What Beijing can do, meanwhile, is to accept that Tibet is not the “happiest land” and this is the result of six decades of the government’s flawed policies. A lasting solution can be found only by understanding messages of self-immolators and addressing their basic aspirations.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.