Obama’s Advantage, Romney’s Openings

Normally, a president presiding over 8 percent unemployment and a country that sees itself on the wrong track wouldn't stand a chance. But then a candidate with Mitt Romney's shortcomings, including his failure to ignite much enthusiasm within his own party, wouldn't stand a chance, either.Normally, a president presiding over 8 percent unemployment and a country that sees itself on the wrong track wouldn’t stand a chance. But then a candidate with Mitt Romney’s shortcomings, including his failure to ignite much enthusiasm within his own party, wouldn’t stand a chance, either.

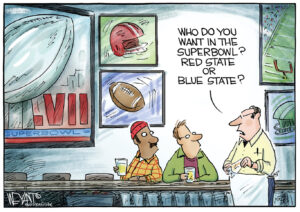

The combination of the two explains why this election remains close, but President Obama heads into the campaign’s last phase with some major advantages, starting, as Ronald Reagan did, with a rock solid base. These voters will support him no matter what the economic numbers say. Their commitment helps create an electoral map that also favors Obama, particularly with Ohio stubbornly retaining a tilt the president’s way.

Obama also has a benefit of the doubt from many voters because they know he inherited an economic catastrophe, a point powerfully made by former President Bill Clinton in Charlotte. And more voters are enthusiastic about Obama, the man, than about Romney, the man. That’s why Team Romney had to spend so much time at the Tampa convention rescuing Romney’s personal image. It also explains the wide energy gap between the two conclaves.

Democrats were so eager to help Obama that it seemed they were ready to cheer even the reading of a phone book or a grocery list. Tampa was flat. Charlotte was hopping.

In fact, the same candidate dominated both conventions. But the centrality of Obama to this election is also where Romney’s advantages begin. If Republicans are rather temperate about their own nominee, they are resolutely determined to oust Obama. This gives Romney at least some maneuvering room with his base.

The economy’s difficulties form the Alpha and the Omega of Romney’s efforts — and the economic reports between now and Election Day seem unlikely to show a sudden spike upward in the country’s financial fortunes. Romney still has time to convince enough voters that they’d be better off if they changed presidents.

Romney will have a money edge. In presidential races, cash gaps don’t make that much of a difference as long as they are not too big, and Obama’s fundraising will at least be competitive. More worrisome to Democrats is how the super PACs financed by billionaires and multimillionaires might affect House and Senate races.

Still, money does buy Romney additional options. The Republicans will have extra dollars to use in trying to make states currently solid or leaning to Obama — Wisconsin, and perhaps Michigan — more competitive. Obama can’t afford to be sucked into contests in states he should be able to count on.

The debates next month are Romney’s biggest opening, and he’s very disciplined in his approach to such encounters. He used them effectively to turn back primary challenges from Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum. The president, on the other hand, is out of practice. And although Obama performed well in the 2008 debates against John McCain by directing almost every word he spoke to swing voters, debating has never been his strongest suit.

Indeed, some of Obama’s most loyal supporters see an additional debate risk for him: The president can look arrogant and dismissive when he doesn’t respect an opponent or when he feels he has the upper hand. Obama can afford no “you’re likable enough, Hillary” moments. Romney will try hard to cause or manufacture them.

Nonetheless, there is a sense after Charlotte that Democrats are on offense in a way Republicans are not. The Charlotte Democrats were unstinting in expressing their devotion to veterans and to the men and women currently serving in our armed forces. They thereby poached on territory Republicans took for granted, thoughtlessly left open to them by Romney. In Charlotte, there was much talk about upward mobility as a family enterprise. This provided Democrats with a traditionalist counterpoint to a GOP that now speaks in relentlessly materialist terms about investment and business.

Democrats also opened up foreign policy as a new campaign front, both in Obama’s own speech and in a forceful and entertaining address by Sen. John Kerry. Foreign policy will only be a marginal issue this year, but it favors Obama — and close elections are won on the margins.

There is, finally, the politics of class. Romney Republicans really do look like the party of very rich people. Persuading Americans that wealthy people have to do even better for the rest of the country to do well is the hardest sell Mitt Romney has to make.

E.J. Dionne’s e-mail address is ejdionne(at)washpost.com.

© 2012, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.