Norman Podhoretz in Black and White

Norman Birnbaum, the noted sociologist and thinker, analyzes two worthy new books, by Thomas L. Jeffers and Benjamin Balint, on the longtime editor of Commentary and the magazine he shaped.Norman Birnbaum analyzes two worthy new books on the longtime editor of Commentary and the magazine he shaped.

“Norman Podhoretz: A Biography,” a new book on the editor of Commentary from 1960 to 1995, by an extremely admiring author, Marquette University professor of English Thomas Jeffers, depicts him as both prophet and martyr. His prophetic status resides in his unequivocal defense of the values expressed in the traditionalism of the conservative minority of American Jewry and its indissoluble attachment to Israel. The U.S., and its Americanized Jewish majority, cannot be counted upon. Eternal vigilance is required if its truly Jewish citizens (and those gentiles insightful and noble enough to rally to their cause) are to keep both Jewry and the U.S. from falling to inner demons. These include, variously, vacuous sentimentalism, multiculturalism, tolerance of homosexuality, pacifism, compulsive egalitarianism, feminism and militant secularism.

Podhoretz is deemed a prophet for having waged this battle, some youthful wavering apart. He is, however, a martyr since he has been constantly damned for it by those who lack his belief in the redemptive qualities of the U.S. Above all, a Jewish majority addicted to “liberalism” persists in a spiritually shallow and morally self-defeating attachment to an American version of Western European social democracy. To make matters worse, that Jewish majority mistakenly believes it is following Jewish teaching. In fact, Podhoretz has insisted for more than 40 years, it is untrue to Judaism, endangering Israel — and undermining the foundations of its prosperity and security in the U.S.

Norman Podhoretz: A Biography

By Thomas L. Jeffers

Cambridge University Press, 408 pages

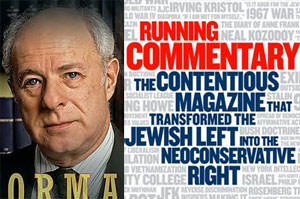

Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right

By Benjamin Balint

PublicAffairs, 304 pages

The author of this contemporary morality tale is obviously in agreement with his subject on every conflict-laden issue mentioned in the text. (On homosexuality, Jeffers and Podhoretz make Justice Antonin Scalia sound rather nuanced.) Ordinarily, a minimum of critical distance is useful to biographers, but Jeffers’ depiction of Podhoretz’s life and works is unwaveringly loyal. The volume may be understood as a family chronicle, written by a distant acquaintance anxious to be numbered among its friends.

Podhoretz once used the term “family” to describe the New York intellectuals of the ’50s and ’60s, a group he joined as a very young man. Much of the readability of his first memoir (he has been repeating and occasionally adding to it ever since), “Making It” (1968), is in the description of the group. They were the editors and major contributors to Commentary and Partisan Review. Jeffers himself is fascinated by the sheer aggressiveness of the group, collectively and individually, takes it as evidence of the group’s moral authenticity and excuses its excesses as spiritual collateral damage. He praises Podhoretz for his capacity to give as good as he gets.

The biography portrays Podhoretz as indeed struggling with large issues: his Jewish identity and his relationship with the U.S., the substance of American history, the nation’s role in the world. A long series of significant public events comprises the outer narrative: postwar prosperity and the integration of the white ethnic groups in the new American consensus; the serial crises of the Cold War; American social criticism and its consequences in the New Left; problems of class, gender, race; and the development of a new Republicanism with notable Jewish intellectual support.

The Podhoretz of the text is, however, not merely an unusually articulate participant in public argument. He is Superman rather than Everyman, emerging triumphant from the inner and outer travails that have reduced the rest of us to exhaustion if not bewilderment. Professor Jeffers makes it clear that whatever else Podhoretz may have acquired on his long journey from Brooklyn to the Upper East Side of Manhattan, he has inexorably shed his doubts.

Biographers frequently dwell on ambivalence, ambiguity, complexity, inner turbulence and the reversals of fate. Very little of that marks this text. As chapter succeeds chapter, its protagonist surmounts inner and outer obstacles to his own personal integration and social success with increasing ease, all the while devoting himself to the education of his people and his nation. Podhoretz began his career as a student of Lionel Trilling and then of his University of Cambridge contemporary, F.R. Leavis. Each was much more moralist than aesthetic formalist, and their student took their lessons so seriously that his writings became increasingly one-dimensional, even stentorian. The colors of Commentary under his influence gradually were reduced to two: black and white.

The book is a mirror rather like the distorting type in a funhouse, the very exaggerations of which tell us much. One has to bring to it a minimum of critical distance. My own reading is aided by the fact that at one point I knew Podhoretz quite well. We have had somewhat similar life experiences. I am mentioned only once, and very incidentally, in the text, but I also knew any number of the major and minor protagonists who people it. Briefly, I first met Podhoretz during visits to New York in the late ’50s and early ’60s, when I was teaching in the United Kingdom. Commentary published articles I wrote, as did Partisan Review. By the time I returned permanently to the U.S., in 1966, he was firmly established as Commentary’s editor, an important figure in the nation’s cultural and political scene. My return to the United States was difficult, inwardly and outwardly. In those years, I had good reason to be grateful for Podhoretz’s friendship and support. I regret that political differences impelled him (not without help from Midge Decter, his wife) to terminate our connection.

Podhoretz was born in Brooklyn in 1930 into the Yiddish-speaking Jewish working class. He grew up in a rough neighborhood marked by ethnic and racial tensions. He was able to take care of himself on the streets, not always true of those who, as he did, excelled at school. His own ambition, the encouragement of a teacher at his public high school, and the hopes of his family enabled him to win a scholarship to Columbia College. Simultaneously, he studied part time at the Jewish Theological Seminary. That was certainly not typical of the Jewish students then profiting from the postwar lowering of the anti-Semitic barriers that had kept many out of elite colleges. The entire postwar generation of Jewish students moved up into business and finance, the cultural industry, the professions and politics. University careers had strong attractions for many of us. We could (or so we thought) continue to live by our wits, enjoy some economic security, and profit from the pronounced influence and prestige of the established private institutions or the surging public ones.Podhoretz went on to graduate study at Cambridge but eschewed the academy’s simultaneous offer of security and imprisonment and became an independent critic. He had been far from welcomed at Cambridge by Leavis, but his decision was not primarily a response to Leavis’ version of Little Englandism. Podhoretz was in a hurry, and the climb up the academic ladder did not appeal to him.

The Jewish ascent in the United States, in any event, followed that of other groups. Many persons we now think of as exemplars of the cultural and social domination of a white Protestant elite often had to fight their way out of small towns to reach metropolitan heights. What is unique, if anything, is Podhoretz’s insistence, sedulously echoed by his biographer, that his success proved the virtue of American civilization. Suppose the nation actually needed the energies and talents of those it half-welcomed to, half-grudgingly ceded, elite status? Podhoretz for a while was very friendly with Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Jews were not alone, in the era of the Kennedys, in surmounting barriers.

Norman Podhoretz: A Biography

By Thomas L. Jeffers

Cambridge University Press, 408 pages

Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right

By Benjamin Balint

PublicAffairs, 304 pages

After serving in the U.S. Army in Germany, Podhoretz returned to New York and soon exchanged freelance status for a junior editorship at Commentary (in 1955, five years before he became editor). The early decades of the journal were quite instructive. Originally the Contemporary Jewish Record, it was renamed in 1945 by its publisher, the American Jewish Committee, then a group intent on the integration of American Jewry in national American culture and quite skeptical of Zionism. Seeking to discern the new patterns of Jewish life in the United States, the journal ventured into cultural and social description of the postwar nation. While describing for New Yorkers the contours and depths of what had been the hinterland, it convinced a national readership that its monthly editions guaranteed them front row seats at New York’s continuously playing theater of ideas. I have amused recollections of Chandler Brossard’s scintillating essay on the problems of a gentile intellectual in New York. Like the Jewish novel of the period, Commentary converted Jewishness into a (relatively) familiar aspect of American culture.

Podhoretz had the instincts of a gifted editor — an ability to identify emerging ideas, cultural and political problems and writers before others did. He transformed Commentary, in his first few years there, into a vanguard journal. The older generation at Partisan Review was so exhausted by the struggles of the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, so anxious lest it lose its self-appointed function as guardian of culture, that it floated uncertainly in historical space. Podhoretz used writers like Dwight Macdonald when it suited him, but brought others forward: James Baldwin, Oscar Gass, Paul Goodman, H. Stuart Hughes, Staughton Lynd, Hans Morgenthau, David Riesman, Barbara Probst Solomon. He had an important role in developing the ideas of the American New Left before the movements that would carry them into the streets were formed. He had allies. Lewis Coser and Irving Howe at Dissent and Willy Morris at Harper’s shared Podhoretz’s intuition that not one but several realignments were proceeding simultaneously. In New York’s Greenwich Village and the Upper East Side, African-American and Jew, Irish Catholic and Southern Baptist, men and women, patrician and social climber, European and American, psychoanalyst and patient, solitary writer and dutiful worker on the cultural assembly line, were discovering to their own astonishment that perhaps they had something in common. What was it?

With the election of John Kennedy in 1960 as our first Catholic president, the offspring of new immigrants who had figured so prominently in Franklin Roosevelt’s and Harry Truman’s governments took command. The educated elites experienced a sense of greatly enlarged possibilities, their allies in the trade unions were determined to profit from their return to power, and American culture struck many of us as more open than we had been prepared to admit. Kennedy himself was—rhetoric apart—a cautious incrementalist in major domestic matters and a determined proponent of American hegemony in foreign policy. By the time he was murdered in 1963, he had more resolve about questions of race, and more reflectiveness about the Cold War. Jeffers hurries past Podhoretz’s editorial mobilization of those who sought just that shift of emphasis in the politics of the nation.

The biographer’s evident discomfort with Podhoretz as political and social critic is surprising. After all, Podhoretz himself has written for five decades of his change of mind. The text provides ample evidence of what bothered him. One event does not quite receive the attention it merits: the mixed reception of “Making It.” I thought the book very good on the New York literary milieu and its honesty about ambition. I recall Podhoretz’s distress at the publisher who having commissioned the book, refused it, at the sententious advice of Trilling not to publish it, at hostile reviews by others. I found Trilling’s fastidiousness absurd: He praised ambition in 19th century English novels, found it distasteful in a student of his from Brooklyn. In the end, the indignation of the critics reinforced Podhoretz’s tendency to think of himself as isolated, his antipathy to other intellectuals. He saw arguments with others as proof of his own virtue.

By 1968, indeed, he had broken decisively with the New Left. He found the tactics and what there was of strategy of the movements for social change mistaken, and aligned himself with the leadership of the AFL-CIO in rejecting them. He abjured the cultural and political separatism, as he saw it, of many of the African-American and feminist leaders. The rejection by much of the student movement of high culture offended him, and he joined with the liberals who dismissed it as adolescent if not infantile self-indulgence. Opposition to the war in Vietnam was no longer a matter of critical distance from imperial power, but became ignoble capitulation to illusions about communism. His criticism changed rapidly from the common sense of an old progressive to the overwrought anxiety of a threatened deacon of the established order. Two specific events precipitated the change. One was the Six-Day War in 1967, and the response to it of the major American Protestant churches and the African-American leadership. With what Podhoretz thought of as suspicious rapidity, they began to regard Israel as an oppressive occupying power in the Palestinian territories. Meanwhile, in New York City, the demand by African-Americans (and Latinos) for local control of schools precipitated a clash with a teachers’ union with a large Jewish membership. Podhoretz connected this to projects for affirmative action as a threat to the position of Jews in government, the professions and in the labor market generally. He was unrestrained, in discussion and print, in denouncing the foundations and especially the Ford Foundation for supporting community control of education. It was, he said, an effort by the older Protestant elites to block and reverse Jewish social ascent.

Podhoretz took up the struggle within the Democratic Party, his allies figures like the leaders of the AFL-CIO (George Meany and then Lane Kirkland), Sen. Henry Jackson. He later shifted his loyalties to the Republican Party but found plenty there to discountenance him. Above all, he opposed the negotiated coexistence with the Soviet Union sought by Henry Kissinger under Nixon and Ford, and later by Reagan and the first Bush. The Soviet leadership was, Podhoretz insisted, implacable and insatiable in its drive for world domination. Its refusal to allow Jewish emigration was another crime. In those circumstances, compromise with it (arms control and other measures of military and political cooperation) was bound to fail. Worse, it was evidence of weakness that would in fact prove fatal not only to our influence in the world, but to our very independence.

Norman Podhoretz: A Biography

By Thomas L. Jeffers

Cambridge University Press, 408 pages

Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right

By Benjamin Balint

PublicAffairs, 304 pages

The collapse of the old Soviet Union served not as an occasion for rethinking, but for retroactive legitimization of a policy of maximal aggressivity. The apocalyptic images of a Soviet threat were transferred, intact, to the dangers of “Islamo-fascism.” That made it possible for Podhoretz, in the past two decades, to simplify an already simple worldview. The fate of civilization now rested not on the familiar defense of “the free world” but on the necessity of total alignment with Israel — provided that Israel was being led by the hardest of governments.

Podhoretz, initially a friend of the older Israeli leaders like Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin, has come to distrust them and their successors. He thinks negotiation with the Palestinians a waste of effort and time, indeed, as an incentive to more terrorism directed at Israel and those who accept its existence. He deplores the inability of many, even a majority, of his fellow Jews to see that their interests, moral and material, require an alliance with Republicans and indeed, with the right of the Republican Party, including the Protestant fundamentalists. These, he insists, are Israel’s truest supporters in gentile America. His vexation with American Jewry is not limited to its alleged casualness about Israel’s fate; he believes American Jews to be self-destructive in their hostility to the liberalism and openness of American capitalism and in their preferences for the American welfare state. After all, he argues, much of the prophetic tradition of social justice refers to the distribution of power and wealth within Old Testament Israel. The others had to look after themselves.

His biographer does not dwell at length on his subject’s return, spiritually, to Brooklyn’s mean streets. He could have portrayed it as the appropriation of major strands of American tradition — a striking synthesis of domestic social Darwinism with a global imperial project. The younger George Bush, as president, awarded Podhoretz the Medal of Freedom and was delighted to learn that Podhoretz admired his achievements.

Podhoretz’s Judaism emphasizes ethnic solidarity, fidelity to tradition and large distrust of a world in which Jehovah neglected to place more Jews. He claims that his interpretation of Jewish history (including the iron obligation of every Jew to make the defense of Israel an absolute priority) brings American Jewry to the American heartland. The U.S. belongs, in the first and last analysis, to those who work tirelessly for success, who depend upon their ethnic communities and churches for help and not upon the state, and who above all suffer no pangs of conscience merely because they prosper and others do not. To the argument that he has Americanized Jewishness, he replies that he has shown how Jewish the American essence is — just as the Puritans with their Old Testament beliefs thought. On this reading, the American alliance with Israel is not a geopolitical and moral choice but a matter of American identity. That is why, presumably, the most determined defenders of Israel are gentile politicians of solid character rather than brilliant intellect. The Jewish exodus from the ghetto resulted in a large degree of intellectual achievement that does not, apparently, strike Podhoretz as entirely positive. Too many Jews in his view think too critically.

Large numbers of American Jews, and large numbers of their fellow citizens, do not accept Podhoretz’s story. He is certain that stringent criticism of his views is evidence for their rightness. Once very friendly with Norman Mailer and Moynihan, he took his distance from them as misguided. Those who have found Podhoretz somewhat heavy, even humorless, may be ignoring something essential. His labored phrases are the work of a man convinced of his direct access to being — a learned and pious figure uncorrupted by the complications and temptations of the Enlightenment.

Podhoretz had sure instincts for contracting intellectual, personal and political alliances — and moving onto other ones when it suited him. In fact, his present position is not that of a defiant iconoclast but of a single-minded defender of the narrow orthodoxy of an inward-turned segment of American Jewry. He is very much the product of circumstances.

There, precisely, lies the value of Benjamin Balint’s history of Commentary, “Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine That Transformed the Jewish Left Into the Neoconservative Right.” It is an account of those circumstances, a short history of a good deal of Jewish intellectuality in the United States. It is very well written, informed by a larger view of American cultural and political life, and conspicuously unhagiographic, even occasionally impious. Balint himself was for a while an editor at Commentary, which makes his measured detachment an achievement. (He interviewed me as part of his research on the book.) Balint had a problem of narrative. Commentary began on the periphery of American intellectual life, moved rapidly toward its center (insofar as we had one), and then moved again, to a well-demarcated site on the side. Was it pushed, or did it march resolutely to its present position as the organ of a vociferous congregation, constantly rebuking its former members for their defection, and insisting on its claims to the truth? He solves the problem by constant reference to the changing concerns of those who, increasingly, set Commentary’s agenda by following their own, that large part of the nation’s community of thinkers and writers who now no longer bother to read it, but did — until about 1975.

In 1945 the idea of a distinctively Jewish contribution to American intellectual life would have struck many, gentiles and Jews alike, as implausible. The interminable debates by community leaders and rabbis on the Americanization of Jewry were deemed unworthy of their attention by many educated American Jews. They were getting on with the process by immersing themselves in American culture. Some had worked for state and federal governments in the New Deal, and the younger ones had been in the armed services. The expanding economy provided places in the professions. Employment in first the universities and later much of business was opening. That in this situation Jewishness was of interest to anyone but Jews was hardly obvious.

Norman Podhoretz: A Biography

By Thomas L. Jeffers

Cambridge University Press, 408 pages

Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right

By Benjamin Balint

PublicAffairs, 304 pages

Commentary’s founding editor, Elliot Cohen, found a way to make it interesting — by concentrating on the process of Americanization. He made the journal into an extended appendix (or better yet, a scorecard) to the Jewish novels that were so widely read after the war. Cohen’s father was an immigrant rabbi in Mobile, Ala., who also had a general store. He went to Yale at a time when it was not especially welcoming to Jewish students, concluded that he could not have an academic career and sought his fortune in literary New York.

Balint gives a great deal of attention to the New York intellectuals, and presents Commentary as an alternative to Partisan Review, self-consciously Jewish where Partisan Review was in his view silent on Jewish issues, including anti-Semitism. Still, its founders, Philip Rahv and William Phillips, were very aware of their Jewishness. I knew Phillips quite well and would say that he was painfully aware of it. And that was true of my friend Clement Greenberg (who later worked at Commentary) as well. Trilling, who was also a major figure at Partisan Review, had an acute Jewish consciousness himself. One could not demand one of Macdonald, Mary McCarthy and Edmund Wilson—although Wilson at one point concerned himself with the Dead Sea Scrolls. He was interested in the Jewish roots of Christianity—and in eruptive social movements.

Balint is right to expend a good deal of his energy on the New York intellectuals’ turn from Marxism, and on their being so much at home in the realm of homelessness, that generalized alienation that marked the spirituality of the past two centuries. Their turn from Marxism was quite consonant with the self-satisfaction that marked much American postwar social thought, occasioned not least by the social integration of even the most ideologically resistant of the intellectuals.

Partisan Review was the work of an older generation, and Commentary was that of a younger one. The younger editors and writers appropriated, and ruthlessly Americanized, the larger themes they took from their elders. As the union movement achieved prosperity for much of the American working class, as many crossed the boundaries of class, ethnic group, region and religion the ideas of the elder generation were domesticated. They still served to organize thought and sensibility, even when they were most strenuously criticized. Supremely able, when at the height of their powers, to seize the spirits of the times, both Phillips and Podhoretz responded very positively to the movements of the ’60s. (Phillips, increasingly breathless in his run to keep up, finally moved Partisan Review into the ’60s in 1971 when he brought Christopher Lasch, Susan Sontag and myself onto the editorial board.) Meanwhile, the one issue that resisted domestication was race. Balint is very honest in his account of the problems it caused Podhoretz — and everyone else.

Despite the clarity and depth of Balint’s grasp of a very complex historical episode (the entry into American academic life and our national culture generally of the Eastern European Jews), he underemphasizes one facet of it. He concentrates on the attraction of the varieties of Marxism to many, on the socialist legacy brought to the U.S. by those who had been part of the Jewish labor movement in Eastern Europe. However (think of Justice Louis Brandeis), as Jews gradually entered American politics and the public sphere decades before the Great Depression, they were drawn to American progressivism. My father was a City College classmate of Sidney Hook and sat with him in the classes of the legendary Morris Raphael Cohen, the obdurately critical philosopher who thought much of Marxism untenable. The books I found at home were not by Lenin and Bukharin, but by the Beards, Dewey, the Lynds and Parrington. The American Communist Party’s Popular Front slogan in the ’30s, “Communism Is 20th Century Americanism,” was on the face of it grotesque, and yet had a certain logic, exemplified in Hook’s attempt to unite Marxism with pragmatism.

The New York intellectuals had plenty of readers in Washington, but in the years from Franklin Roosevelt through Jimmy Carter sent no one there. They were represented, to some degree, by John Kenneth Galbraith and Arthur Schlesinger, progressives by birthright. Michael Harrington appears in the text as a voice of social conscience. Like Moynihan, his spiritual roots lie in the Catholic segment of the labor movement, which is a large presence in the background of the book, one that might have had more explicit attention.No small number of the Jewish intellectuals depicted themselves as authentic latter-day saints, a prophetic minority bringing arcane truths to those who would otherwise have wandered blindly in the wilderness. Many of them not only experienced but avowed a bewilderingly rapid and acutely contradictory sequence of beliefs, from one or another variety of Marxism to aesthetic modernism to philosophical existentialism, before ending either in American progressivism with its idea of a continuing, if contained, revolution, or American conservatism with its insistence on an achieved one. Some shared with their more mundane brothers-in-law skills at marketing—above all, themselves.

Balint provides us with a learned guidebook to the intellectual and political travails of successive generations. The book is rich in excerpts from correspondence, and telling in citations from articles and books. The author takes no one quite at face value, and yet dismisses none of the protagonists as entirely dubious, although some were. He is especially informative in describing the alliance between the present generation of Commentary editors and authors and the Republican Party, a much closer one than the jagged connection between the earlier journal and the Democrats. Despite being an alumnus, Balint is straightforward in noting that Commentary’s editing for a long time has had the ideological consistency and rigor we once associated with what was termed the party line.

Norman Podhoretz: A Biography

By Thomas L. Jeffers

Cambridge University Press, 408 pages

Running Commentary: The Contentious Magazine that Transformed the Jewish Left into the Neoconservative Right

By Benjamin Balint

PublicAffairs, 304 pages

At one point he may err on the side of generosity, repeating the late Irving Kristol’s denial that he knew of CIA funding of the monthly Encounter, of which he was founding editor. I was in the United Kingdom in those years and was greatly helped when confronting the claim by recourse to the history of medieval Catholicism, with its doctrine of two truths, one for the ordinary believers and one for theologians.

I read the book as I was half celebrating, half struggling with, my 84th birthday. I was reminded of 1976, when Podhoretz published an article sternly critical of President Ford and Kissinger for weakness toward the Soviet Union (“Making the World Safe for Communism,” in the April 1976 Commentary). I was well able to restrain my enthusiasm for Kissinger. We had been fellow teaching assistants at Harvard. Indeed, for a long time I dined out in the American suburbs and European provinces on the claim (which has the merit of being true) that I was the chief assistant in the course in which he began his teaching career. However, I thought in 1976 and think even more strongly now that he (and Nixon and Ford) were quite right to seek coexistence with both China and the USSR. In 1976, I was on the editorial board of Partisan Review and quite friendly with William Phillips. William phoned and suggested that we do something about the piece. You mean, William, I replied, that I ought to write something? He did and I wrote a response (“Norman Podhoretz’s War,” Partisan Review, No. 2, 1976).

At the time, I must have been one of the few old friends of opposed political views still in touch with the Podhoretz family. I phoned Norman to tell him that I was sending him an advance copy of the article, and to assure him that it was a criticism of his views and not of his person. He expressed considerable skepticism on this point, instantly, but I urged him to wait until he had read what I wrote. Midge Decter, at the time was an editor at Basic Books and had invited me to a party at their apartment in honor of an author, their upstairs neighbor on West End Avenue, the gifted psychoanalyst Leslie Farber. It was a year during which I was in Princeton, and I scheduled a lunch at New Brunswick in New Jersey with Phillips at Partisan Review before the Podhoretz reception.

Just before I left, Midge telephoned. Her voice was such that the old land lines seemed unnecessary, and from its tonality I instantly guessed what was coming. “I am tired,” she said, “of these attacks on us and I am uninviting you from the party.” Norman was, apparently, not consulted since he later made the gesture of asking me to contribute, for the last time, to a Commentary symposium. I went to New Brunswick to recount the episode to Phillips. “Outrageous,” he declared. “They did not invite me so they can’t uninvite me.” Years earlier I had asked my Hampstead neighbor, George Lichtheim, what he thought of New York intellectual life after a year at Commentary. It reminds me, declared the very well mannered son of a wealthy Berlin family (rather like the ones Hannah Arendt and Herbert Marcuse came from), of nothing so much as an especially quarrelsome East European Jewish family. One sees what he meant.

Norman Birnbaum is university professor emeritus, Georgetown University Law Center, and on the editorial board of The Nation. From 1971 to 1983 he was on the board of Partisan Review, and he contributed regularly to Commentary between 1956 and 1976. He is writing a memoir, “From the Bronx to Oxford—And Not Quite Back.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.