No Mickey in This ‘Maus’

Art Spiegelman's “MetaMaus” is a 300-page user's guide to his own Pulitzer Prize-winning “Maus” (you know, Holocaust-graphic-novel-Jews-as-mice-Nazis-as-cats).

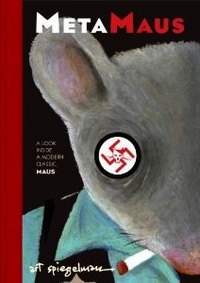

“MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern, Classic Maus”

A book by Art Spiegelman

When critiquing a book about another book, the reviewer is faced with a dilemma: Should he erase any prior views about the original work, making his arguments for or against the secondary work objectively? Or does he anchor his heels squarely in his preexisting interpretation of the original work, and judge the success of the secondary work by how closely it jibes with the reviewer’s opinion? On the rare occasion when the original work has acquired a cultural significance larger than the mere reading of its text, and the secondary work is ambitious and broad enough to reflect on both the original book and its influence on society, then a reviewer is free to critique from both perspectives. Art Spiegelman’s “MetaMaus,” the 300-page user’s guide to the spiritual physics and existential biology of his own Pulitzer Prize-winning “Maus” published 25 years ago, is such a book.

My biggest fear upon learning about MetaMaus was that it would be an artistic and cultural vivisection, as if the best way to appreciate a painting was to dissect the artist’s brush and examine the integrity of each individual bristle, or a Shakespeare sonnet could be understood only if processed through the large and small intestine of a liberal arts education. I’d seen it happen innumerable times before with academic scholarship, this taxidermy of something meaningful only in motion and emitting its own heat, and I found myself damning Art Spiegelman for allowing it to happen.

Then I found out that the deconstruction of “MetaMaus” would be conducted entirely by Spiegelman himself, with the majority of text culled from taped conversations between him and Hillary Chute, currently in the English department at the University of Chicago and previously a junior fellow in literature at Harvard. Then I found out that the book would include, in addition to hundreds of historical documents, sketches and character studies from Spiegelman’s private notebooks, a digitized archive of, among other things, audio interviews with his father, Vladek, upon whose story “Maus” is based. Then I decided to ignore my own disdain for bibliology and refrain from judging a book by its cover, or, more accurately — and in the spirit of battling back against a genocidal mind-set, at least in those much more psychotic than myself — judging a book by its brothers.

I first read both volumes of Spiegelman’s comic book masterpiece in 1993 when I was in my mid-20s, approximately the same age that Spiegelman was when he first strapped on his mouse mask and set cartooning pen to Poland. Unlike Spiegelman, however, when I was 27 years old I lacked the wisdom and maturity to recognize what an artist’s responsibility might be to both the past and the present. I remember being willfully unimpressed with, first, the artwork, and second, the narrative, as if the subject matter could’ve been saved by a less BEK-meets-“Little Orphan Annie” rendering or a more heroic protagonist or a less ambiguous denouement.

My deliberate attempt to avoid being swallowed up by “Maus” when I was a young cartoonist was, ironically, precisely the same white-knuckled stab at distance and intellectual sobriety that Spiegelman hoped for while composing the work. He was always fearful of tripping and falling headlong into the familial dysfunction and the slippery tricks of memory that threatened to corrupt the retelling of his father’s experience as a Holocaust survivor. Spiegelman explains to Chute in “MetaMaus”:

The subject of Maus is the retrieval of memory and ultimately, the creation of memory. The story of Maus isn’t just the story of a son having problems with his father, and it’s not just the story of what a father lived through. It’s about a cartoonist trying to envision what his father went through. It’s about choices being made, of finding what one can tell, and what one can reveal, and what one can reveal beyond what one knows one is revealing.

|

To see long excerpts from “MetaMaus” at Google Books, click here. |

When, in the early spring of 2009, I was assigned the task of rereading “Maus” by an editor at Random House who had asked me to write a graphic memoir and wanted me to avoid inadvertently borrowing too heavily from the innovators of the art form, my deep appreciation for the book(s) finally — and thankfully! — came to the fore. The genius of “Maus” never resided with the author’s overt artistic abilities, but rather had everything to do with his ability as a curator of both his father’s tale and the process by which all tales are told and then passed around as if they were recipes — recipes tweaked for taste, made sweeter or saltier or slightly more tart depending on the occasion, and whether the meal’s purpose is to sustain us or entertain our palate.

Wisely examined throughout “MetaMaus” is how “Maus” adheres to the strange dramaturgy specific to the Holocaust. It was a remarkably ghoulish event that inspired no archetypal heroes, nor did it provide a meaningful testing ground for moral fortitude. Whereas most top-selling books typically involve a protagonist whose depth of character is revealed by his or her eagerness to be shaped by unique experiences, Holocaust stories are the antithesis of this prototype. The reason for this, of course, is because there is only one strategy for survival inside a concentration camp, and that is to avoid any and all ostentatious feats of bravery or self-actualization. For the protagonist of a Holocaust story to live another day, he or she must be as inactive as possible and pray that nothing happens, that inactivity helping to camouflage him or her from the bloodlust of his or her captor. Included midway through “MetaMaus” are the many rejection notes that Spiegelman received when first attempting to publish “Maus” in the early ’80s. What is remarkable is how logically they are able to argue against carrying the book. Congdon & Weed complained that, “Once one becomes accustomed to the characters having been done in animal visage, then the book becomes simply a holocaust tale.” Penguin said, “… I don’t think ‘Maus’ is a completely successful work. … In putting such charged personal material into comic strip form, one would expect something very new, and that doesn’t really happen.” What publishers seemed to find troubling about “Maus” was its tendency to come across more like a found object than a malleable blob of sculptor’s clay.

“There’s a phrase Ren Weschler used in a beautifully written essay about ‘Maus,’ ” Spiegelman remembers in “MetaMaus.” “The phrase delighted me as a concise acknowledgment of what I strived so hard for in telling the story. He talked about the book’s ‘crystalline ambiguity.’ If I couldn’t determine a character’s motives, it wouldn’t have been correct to imply those motives, but rather to just explain what happened and allow one to make one’s own determination.”

Instead of something that could be tweaked by the marketing department and made exciting to the consumer class, publishing houses were presented with something that, thanks to Spiegelman’s archeologically sound excavation of his subject matter, was capable of breathing outside the bombastic publicity and royalty racket of the literary industry. It was a “Maus” without a Mickey. It was a cartoon that allowed the ruthlessness of physics and mortality to threaten its participants.

If “Maus” hoped to reveal certain truths about our species through an examination of Spiegelman’s relationship with his survivor father, then “MetaMaus,” by examining Spiegelman’s relationship with his own artistry, gives further credibility to the artist’s oeuvre by demonstrating both the soundness of his technique and the suitability of the instruments used in the extraction of truth and beauty, the warts and the wares, from our common experience of existence. Spiegelman writes in “MetaMaus”:

All kinds of elisions and ellipses and compressions are a part of any shaped work, and my goal was to not betray what I could find out or what I heard or what I knew but to give a shape to it. But giving shape also involves, by definition, the risk of distorting the underlying reality. Perhaps the only honest way to present such material is to say: “Here are all the documents I used, you go through them. And here’s a twelve-foot shelf of works to give these documents context, and here’s like thousands of hours of tape recording, and here’s a bunch of photographs to look at. Now, go make yourself a Maus!”

The simplicity and precision of Chute’s questions contribute to the success of “MetaMaus.” At times, they resound with a therapist’s keen ear for honesty and, yes, psychological relevance to the health and well-being of her subject. There are many comics about the Holocaust now. … How does that make you feel? Did you feel beleaguered doing publicity for “Maus”? Are you sad about [your parents having missed your worldwide success]? Was your anger at Vladek about burning your mother’s notebooks something that affected your interview process with him? These are questions typically addressed to a person lying down with easy access to a box of Kleenex. They are intimate questions that demand that a person give public voice to his or her most private thoughts. They are certainly not questions that inflate an artist’s celebrity or maintain a respectful and disserviceable distance between audience and writer.

Add brainier questions such as, “People often confuse comics for a genre, instead of a medium — why?” and “Did an awareness of modernism inform how you structured the book?” and the result is a dialogue so rich in emotional color and intellectual detail that it succeeds in becoming, not just a journey into one man’s creative process, but art in itself.

“Look, suffering doesn’t make you better, it just makes you suffer!” Spiegelman tells us in “MetaMaus,” reminding us that the Holocaust should never be misconstrued as a lesson in humanitarianism and that mass slaughter, particularly the sort perpetrated by stoking the fires inside Germanic ovens, in no way increases our collective wisdom as a species. At the end of “MetaMaus,” he describes “Maus” as a “three-hundred-page yahrzeit candle,” which, in Hebrew, is a soul candle lit in memory of the dead.

Everything in “MetaMaus,” whether through brilliant conversation, personal essay, historic documentation or stunning artwork, is thoughtful instruction on the handling of matches, our fascination with fire and our troubled relationship with the light it casts.

Mr. Fish lives in Philadelphia. He never asked to be born. Occasionally, he laughs his head off. His mother has no idea what he’s up to. She cries very easily. For more information, date him.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.