Nicholas von Hoffman on Kevin Phillips’ ‘Bad Money’

An insightful book discloses how a confidence game combined pride and cunning and stupidity to bring America to the brink of catastrophe.

Americans, rich or poor, have consciously or otherwise bought into the master-nation proposition that really bad things do not happen to the USA. We might suffer setbacks and commit a blunder once in a while, but we are too big, too rich, too smart, too powerful and too blessed to be visited by a national catastrophe. That the whole goddamn economy could melt right out from under our feet is an unimaginable event, an occurrence out of history when crackly voiced recordings captured President Franklin Roosevelt talking to the Okies.

Such disasters may overtake Argentines or Malaysians or Bulgarians or Russians or even, occasionally, the English, but not the red, white and blue über-nation. Yet in the space of a year the U.S. has gone from über-nation to under-nation, or at least a nation under water as hundreds of thousands have lost their jobs, been tossed out of their homes and seen the savings of a lifetime decimated. Americans have seen many of the most respected business institutions revealed as organizations run by confidence men whose cupidity is yoked to their pride and their stupidity in believing that they could run their ruinous games forever.

At this juncture the dimensions of the disaster are not clear. An honest count would show 10 or 11 percent of the labor force is out of work. If the numbers continue to climb at the present rate, by this time next year they will begin to match those of the gray days of the New Deal era.

By then we may begin to tell each other that none of this misery had to happen. There was no end of warnings and no one was more prescient or more persistent in foretelling what lay in store for us than Kevin Phillips. In the long run up to the vortex, Phillips was one of those who repeatedly warned of what was coming. No one did it more cogently, more learnedly and more forcefully than he.

In his new book, “Bad Money,” Phillips discusses why so few paid attention to a topic so important to their own well-being.

“Many people today think that today’s finance is too complicated for ordinary citizens to fathom or handle. Bubbles aside, other financial terms used by the media — credit derivatives, securitization, and even current account deficit — do not lend themselves to conversations in neighborhood bars or beauty parlors. Americans are excusing themselves accordingly,” writes Phillips. “Still, if the farmers of more than a century ago could study and understand Sherman Silver Purchase Act provisions and details of the nationwide currency shrinkage — and many studied and somehow managed — can’t we expect as much today?”

Answering his own question, Phillips says, “Alas, probably not,” and, given that many 21st-century Americans have the power of concentration of a flea with attention deficit disorder, one cannot argue with him.

Had they heeded what he was saying, the disaster engulfing them and much of the world might have been mitigated. But it is still not too late to learn from Phillips. “Bad Money” is a map describing the economic terrain in which we are struggling to stay upright and slightly solvent. It is a clearly written treatise demanding no knowledge of Greek letter formulas, one which ought to command the attention and interest of such non-fleas as there may be left among us.

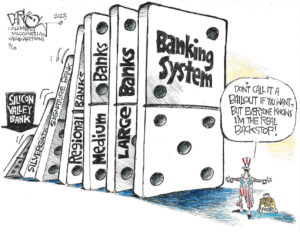

For them this is a useful book because it does not address bailouts and the other hysterical emergency measures which dominate the news, stopgap remedies and economic analgesics though they may be. Temporary relief from pain not withstanding, Kevin Phillips lays out the actualities which must be dealt with before the throbbing will stop.

He begins by describing a distorted economy whose profits have no material reality other than notations on paper or electronic digits. That is the bad money from which the book draws its title, sterile money, not so much earned as won by financial manipulations and “products” whose names we have just recently learned, to our loss.

Phillips quotes Raymond Dalio of Bridgewater Associates: “The money that’s made for manufacturing stuff is a pittance in comparison to the amount of money made from shuffling money around. Forty-four percent of all corporate profits in the U.S. come from the financial sector compared with only 10 percent from the manufacturing center.”

Sixty years ago, Phillips writes, about 30 percent of the American gross domestic product was attributable to manufactures and about 10 percent to financial. The numbers now are approximately reversed. Until recent times the United States made its living across the globe by selling manufactures and raw material. In our time, however, under the aegis of the new economy the nation has tried to live by selling nugatory services of a vaguely financial nature to foreigners who have not been buying enough to keep the American economy from going deeper into the red, year upon year.

“… [T]his faith in finance was not new, but old — and it played wayward Pied Piper to prior leading world economic powers,” Phillips writes. “On the edge of decline the Spanish had gloried in their New World gold and silver; the Dutch, in their investment income and lending to princes and czarinas; and the British, in their banks, brokers, and global financial network. In none of these situations, however, could financial services succeed in upholding the national preeminence that had been earlier built by explorers, conquistadores, maritime skills, innovative science and engineering, the first railroads, electrical dynamos, and great iron and steel works. Invariably, power and greatness passed to new explorers, innovators, and industrialists.” He quotes an admonitory passage to the same effect from a 1904 speech to his nation’s bankers by British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain which might apply to the United States 104 years later: “Granted that you are the clearinghouse of the world, [but] are you entirely beyond anxiety as to the permanence of your great position? … Banking is not the creator of our prosperity, but it is the creation of it. It is not the cause of our wealth, but it is the consequence of our wealth.”

With the ascendancy of finance comes the maldistribution of capital. Money is invested in the wrong places. Gigantic amounts of capital are borrowed for unproductive purpose, for things which have no payback. “The debt the United States has been piling on in the last few years has provided only 30-40 percent as much stimulus per dollar to the national economy as did the debt added 25 or 40 years ago. Why?” Phillips asks. “Because money borrowed in 1970 or 1984 to be spent on factories, new jet fighter aircraft, teachers, or interstate highways had a lot more grassroots impact than money borrowed by 10,000 hedge funds to double the leverage of their various self-serving speculations.”

Roads, factories, research, productive companies, education are undercapitalized, the money which might have been sent in their direction having been sucked off into the catastrophic frivolities of Wall Street, Greenwich, Conn., and wasteful finance. Capital which ought to have been used to lower costs and increase productivity was used to play the destructive games which have left once healthy corporate organizations gasping for breath, too weak to modernize, too depleted to compete and too fragile to prosper.

The distraining of capital to all the wrong places was accompanied by the debt-credit explosion. As pesky and difficult as contending with public indebtedness, especially the federal deficit, is, Phillips foresaw that it is private-sector debt which is likely to destroy us. On this he quotes Warren Buffett, another figure who warned that the country was steering toward catastrophe: “You can’t turn a financial toad into a prince by securitizing it. … Wall Street started believing its own PR on this — they started holding the stuff themselves, maybe because they couldn’t sell it. It worked wonderfully until it didn’t work at all. Wall Street is reaping what they’ve sown.”

Beyond Wall Street’s suffering for Wall Street’s crimes, Phillips describes the American descent into a debt-dependent economy in which the most important activities have been building subdivisions and erecting malls with money borrowed from abroad. The middle-class masses drive home to the houses they cannot afford and zoom off to overly hypothecated malls, using oil they have no means to pay for, in order to incur additional debt on their credit cards.

The risks of a financial system constructed of toothpicks were plain to Phillips and scores of others outside of it and to none within. With the assistance of battalions of idiot savants from MIT and Harvard, the much admired math “quants,” the investment bankers boasted that they had found a way to ensure that the more borrowed the less the risk.

While Wall Street entertained the fantasy that it had perfected an algorithm which had eliminated risk from the financial equation, ordinary people were finding their lives increasingly uncertain. The ascent of Wall Street to something approximating total power, however brief that reign may be, has brought with it awareness of the disparities of wealth and income. Less publicity has been given to how much riskier life has become for America’s middle class.

Ordinary families face a 1-in-5 chance of seeing their incomes drop by half, according to figures compiled before the present “slowdown” or “slump” or “weakening” or recession. Phillips recalls the work of Harvard’s Elizabeth Warren, quoting her that “middle-class families have been threatened on every front. … Even with two paychecks, family finances are stretched so thin that a very small misstep can leave them in crisis. As tough as life has become for married couples, single-parent families face even more financial obstacles in trying to carve out middle-class lives on a single paycheck. And at the same time that families are facing higher costs and increased risks, the old-fashioned rules of credit have been rewritten by powerful corporate interests that see middle-class families as the spoils of political influence.”

As for the future, Phillips’ attitude is decidedly saturnine. Long years of national prosperity and success, he fears, breed political arteriosclerosis, making change next to impossible. His assessment of the Democrats is anything but hopeful: “Gone on the Democratic side is the southern and western geography of opposition to northeastern financial elites under the aegis of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman. Instead, there is a new democratic politics of new national elites — financial, high-tech and communications. … For both parties, the bottom line is usually the same: the bottom line. Fundraising. Money.”

“Bad Money” was finished before Barack Obama secured the Democratic nomination, but the points Phillips makes about the connection between Wall Street and the Democratic Party are still germane. Robert Rubin, an oft mentioned Obama adviser, was Bill Clinton’s secretary of the treasury and is an ex-CEO of Goldman Sachs and presently in top management at Citigroup. Of Rubin and the other Wall Street Democrats, Phillips writes: “The new profinance Democrats were not the same as the older profinance Republicans. They were more engaging, less out of the Union League of Philadelphia or 1950s New Yorker cartoons. Behind the scenes, some might contentedly bailout endangered bondholders, put impoverished nations through the behavioral wringer of the International Monetary Fund, or operate consumer finance units that bilked a lower income clientele. But in their public personas, most took a different tack. In deference to their multiple Democratic coalition-mates, they donated to the NAACP; joined the boards of environmental groups; embraced technology, education, free trade and globalization; and worried about the growing international gap between the rich and the poor as well as the gap in the United States. There was also, as we’ve seen, another broader enabler: the new popular acceptance of finance.”

This is not the message of rebirth and hope of the Obama campaign, but Phillips has a long track record and a good one. He is no man to ignore.

Nicholas von Hoffman, a former columnist for The Washington Post and a former commentator for CBS’ “60 Minutes,” is a regular columnist for The New York Observer. He is the author of numerous books, including “Hoax: Why Americans Are Suckered by White House Lies” and “Capitalist Fools: Tales of American Business From Carnegie to Forbes to the Milken Gang.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.