Neoliberalism’s Zero Hour in the Heartland

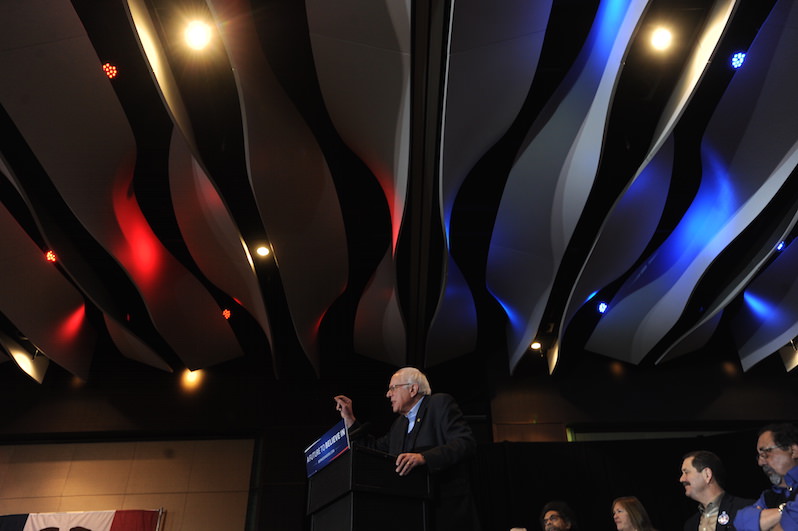

Will Monday's caucus in Iowa open the door wider to the political insurgents and leave the traditionalists gulping Xanax? Or will it expose Big Change as just a brief burst of lightning? Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders speaks at a rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on Saturday. (Dennis Van Tine / MediaPunch / IPX)

Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders speaks at a rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on Saturday. (Dennis Van Tine / MediaPunch / IPX)

By Alan MinskyThis is the first of a two-part series on the Iowa caucuses and the 2016 run for the White House.

In the week before the first contest of the 2016 American presidential election, the pundits have arrived at a consensus: This is the year of the anti-establishment. Bernie Sanders’ meteoric rise in the polls since New Year’s Day means he can no longer be ignored. Now it’s not just the crazy GOP. Both parties are under siege from radical insurgents previously assumed to be outside the bounds of national politics. It’s a delicious moment. America’s corrupt political class is in a panic.

Of course, “anti-establishment” is an anodyne term, sufficiently vague to satisfy a wide range of interpretations. The democratic rebellion of 2015-16 is defined by something singular, however: a widespread loss of faith in the central myth of American society. For most people, the American Dream is dead or dying.

Only a few years ago, new-home ownership was easily attainable, albeit through a Ponzi scheme that ended in disaster. Nowadays the American economy feels like a trap, a spider’s web of debt servitude, a labyrinth of dead ends, longer work hours and ever-limiting horizons. Thirty-five years after the Thatcher/Reagan revolution, we have to consider whether this economic system, this variation of capitalism, can generate even the illusion of working for the average person.

Fortunately, people don’t readily abandon “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” when they’ve been promised them their entire lives. So, given the opportunity to support candidates who not only say the word “change” but may actually mean it and who are advocating policies that run counter to the current order, Americans are staging a rebellion using a weapon the oligarchs thought they’d neutralized: democracy. After six months of prologue, voting begins Monday—and all eyes are on Iowa.

In so many ways, Iowa is not reflective of contemporary America. It is too white, too non-urban, too non-suburban, and far too many of its small towns maintain a semblance of cohesion. Regarding the first example, there’s no escaping how Iowa’s oversized role in selecting the next president diminishes the influence of people of color in the process, sending a clear signal that white supremacy remains a signature component of American democracy. Indeed, at the very moment the presidential race gains definition, the greatest endemic problems in our society—those rooted in our race/class system of exploitation—have little influence. This truth should never be forgotten when reflecting on the Iowa caucus; it is a de facto mechanism to secure the maintenance of white supremacy.

In one way, however, Iowa is just like the rest of 21st century America: The people of Iowa work very hard, but their gains tide them over only until they’re back in the fields. While others make big profits from their labor, what they produce magically morphs into a financial instrument that can generate spectacular gains for—guess who? The 1 percent. Iowa does provide a unique window into these dynamics.

The Hawkeye State is, of course, a land of spectacular agricultural efficiency. Viewed from space, it is the centerpiece of the best-operating and most important mass production “factory” on earth, annually generating the most bountiful harvests in human history. As such, it is one of the — if not the — most important assets of the American imperium. So, how have Iowans been doing farming the land, which, unlike manufacturing, cannot be off-shored?

The past five years have been generally good for Iowa farmers, as cheap oil and record-low interest rates have kept overheads down, resulting in profits. American farmers long ago adjusted to the era of corporate domination following the great crisis for family farmers in the late ’70 and early ’80s. So while things have been OK for the farmers themselves, most of the gains go to Big Agro.

Beyond farming, Iowa is no slouch. The state hosts a healthy manufacturing sector, as well as a slice of the insurance industry. Given all that, it’s no surprise that unemployment is well below the national average.

So, things are working out well for Iowans, right? Guess again. Just like the rest of the country, in the words of University of Iowa professor Stephen Vlastos, “There’s long-term income stagnation; and people feel they are working too hard, with too little security, for too little.”

Where does all the wealth that Iowa generates go? As mentioned, agricultural profits flow mainly to corporations. And then there’s the role that the breadbasket of the world plays in speculative finance. If we once again imagine looking down from space, we can see Iowa as a linchpin of the 21st century global economy, much like the massive Foxconn factories in China that produce an avalanche of digital devices. And like virtually every part of that global economy, Iowa’s production becomes financialized, as both a salable commodity and an instrument for speculation. In 2007-08, Goldman Sachs was accused of causing a global food crisis by manipulating the price of wheat on what was then called the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (since renamed the S&P GSCI)—and, you might recall, the Arab Spring of 2011 was largely sparked by higher prices for food staples, due to financial speculation in food commodities. Tragedy and geopolitical instability? Goldman Sachs could not care less. The company made a killing.

Back in Iowa, there’s little awareness of these specific episodes, but there is a general sense that the wealth produced on Iowa farms—like all wealth in the 21st century—winds its way upward, generating massive returns for someone who never plowed a field and does not have a conscience. So, add resentment to the dismay over stagnant wages, and in the words of professor Vlastos, there’s widespread “discontent with the status quo.” Not surprisingly, this has translated into support for Donald Trump and Sanders.There is, of course, a world of difference between Trump and Sanders. One is a truly reprehensible, if comically boorish, bigot; the other is a serious legislator who sincerely tries to work for the common good. But until we are past this political season, they will frequently be discussed together, primarily for their parallel success and shared status as outsiders. But I see an even more important similarity: They both challenge the status quo by rejecting the logic of the prevailing economic order—the very bedrock of contemporary American social organization—although Trump does so selectively while Sanders’ rebellion is systemic.

Trump is an exploitative capitalist, proudly among the 1 percent of the 1 percent. His political beliefs are grounded in an America-first jingoism reminiscent of militaristic patriots in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. Guided by this John Wayne worldview, he will “make America great again.”

While the stated reason the GOP establishment rejected Trump during the summer and fall of 2015 was for his vulgar bigotry (anything more than dog-whistle bigotry could not be tolerated by a party that needs support from people of color if it ever hopes to win a national election again), perhaps the real reason Trump was deemed persona non grata was that he rejected the free trade deals that are the foundation of the global neoliberal order. Instead Trump called for old-fashioned national protectionism. He told his working- and middle-class constituents that he would deploy his masterful deal-making skills on their behalf; “tell the Chinese how it’s going to be”; and bring back well-paying manufacturing jobs, the very type that have poured out of the country in the era of free trade.

While Trump received nonstop coverage in the summer and fall of 2015, commentators consistently skipped this essential aspect of his appeal. Working- and middle-class Americans, even ones stupid enough to be unreconstituted bigots, understand the game is rigged against them. Trump speaks directly to this economic anxiety, as he promises to dismantle the global economic order and once again “put America’s interests first.” Of course, Trump’s nativism and xenophobia are constitutive elements of his “protectionism.”

It’s crass, hateful bigotry, but it also represents a break with the neoliberal economic order that has been devastating to American workers, and of course it makes him unacceptable to the status quo. In these two ways, and these two ways only—the break with neoliberal logic and the challenge to the status quo—he is similar to Sanders.

In November 2014, I wrote an article for Truthdig that, among other things, considered Sanders’ prospects as a Democratic presidential candidate. Not to brag, but it is the most prescient article on Sanders that I’ve seen—very optimistic about the impact he could make by running. Yet even I am astonished at what Sanders has achieved over the past couple of months, and I’m equally amazed that friends and I have seriously discussed what he could accomplish in the White House.

But first, praise. In his mid-70s, Sanders is truly beginning to resemble his lifelong hero, Eugene Debs, who spoke to overflow audiences across the country as he ran for president as a Socialist in the early 20th century. In recent weeks, Sanders has been taking a star’s turn on the stage of history in the role of hero. It suits him, which shouldn’t be a surprise. Unlike many prominent Democrats, Sanders has a backbone; he believes wholeheartedly in the programs he proposes and defends them with passion—and he never pulls any punches when calling out the mendacity of the oligarchs, nor does he turn a blind eye to the problems people face daily in America. He is their champion and he sincerely wants what is best for them. The crowds feel this, and as he grows more comfortable in the limelight, his playful humor and common decency become more apparent, further cementing the adoration of his millions of supporters.

When Sanders announced his candidacy, expectations were low. Supporters were grateful that his scathing critique of America’s economic inequality would get a hearing, but few thought his proposed solutions would attract attention, offhand dismissal being the norm for progressive policies. But right away it became evident that something was different. Sanders’ catalog of American social ills was surprisingly well received; and you could hear its echo not only from Trump but from other Republicans (who were happy to blame Obama), and Hillary Clinton frequently joined the chorus, too.

But only Sanders had been on this agenda for decades—and herein the seeds of his momentum were sown: Only he could explain the depths of the domestic crises; only he would fully direct his ire at the rich and powerful (who funded the other candidates, save Trump, who was rich and powerful himself) and, lastly, only Sanders had solutions that addressed the full scope of the problems. So, up he went in the polls, rising spectacularly through late summer, until Clinton had her good week in October and then Islamic State pushed domestic concerns into the background for much of the fall. Still, Sanders kept on his game. Flying under the radar, Bernie mania kept growing, and by the dawn of 2016, Clinton had a hauntingly familiar problem: A charismatic candidate was closing the gap, just as in ’08.

By mid-January, Sanders was ahead in New Hampshire and neck and neck with Clinton in Iowa.

Then, suddenly, a couple of days ago the campaign entered a new phase. What seemed like unstoppable momentum only last week must now clear the significant hurdle of Iowa at the very time that Sanders must counter scathing criticism from two formidable adversaries: Clinton herself, and what a Marxist would call representatives of Capital but in America are known as liberal intellectuals.These days, Clinton can seem like an anachronism. The 2016 campaign is the first presidential race without an incumbent since the Wall Street collapse sparked the Great Recession. Goldman Sachs and investment bankers in general are now frequently seen as social pariahs. Yet Clinton does little to hide her strong Wall Street ties.

Of course, the Clintons burst onto the national scene in 1992 as New Democrats who felt their party needed the support of a significant portion of corporate America if it was ever going to wrest the White House away from the GOP. Wall Street and Silicon Valley had loads of money, as well as socially liberal values more in tune with Democrats than the reactionary Republicans. A de facto coalition resulted that has defined the party establishment to this day. What was novel, and perhaps necessary, for victory 24 years ago, however, does not sit so well with many Democrats today, who tend to resent (or worse) Wall Street and probably feel that demographic shifts favor Democrats nationally to such a degree that there’s no need to rely on shady alliances, no matter how much money results.

Yet, both Clinton’s attacks on Sanders and those from prominent liberal intellectuals such as Paul Krugman and Ezra Klein remain grounded in the logic of the New Democrats that consistently prioritizes the need to work cooperatively with corporations over the need to rectify social injustices. Nowhere is this more clear than in the current health care debate between the two campaigns and their surrogates. Clinton, Krugman and Klein all herald Obamacare and advocate for working to make incremental improvements within its structure. This not only guarantees that for-profit private insurance companies remain at the center of the American system, it mandates that they will get ever more business, even though premiums continue to fluctuate erratically and deductibles are often outrageously high, both of which would be absent in a single-payer system.

It’s difficult to hear Clinton and Krugman promote Obamacare over single-payer when neither will ever be in the position of millions of Americans struggling to afford the cost of health care in this for-profit system. It’s even more troubling when the attacks on Sanders stray into slander with suggestions that he would readily sacrifice Obamacare’s gains or even every aspect of government support (Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) in pursuit of his perfect vision.

On the eve of the Iowa caucus, it doesn’t feel as if these late attacks have damaged Sanders, but they do raise perhaps the most fundamental question about a left-wing insurgent candidate in the era of neoliberalism: Is it possible to transform the economy, to make it more equitable, through the democratic process? Sanders certainly believes it is, while Clinton feels only incremental improvements are possible. In part two of this essay, we’ll address this question and consider the degree to which Sanders’ version of democratic socialism is truly anathema to corporate America—the most powerful institutions in the land—as well as whether the “political revolution” he acknowledges as necessary for the economic change he advocates is truly being developed. We’ll also analyze the results of Monday’s Iowa caucus.

Some final, pre-caucus thoughts from Ames, Iowa:

While the combined power of Clinton, Krugman and Klein may not impact Sanders, a winter storm could prove devastating to the man from northern Vermont. Snowfall is scheduled to hit the state Monday evening, and inclement weather is considered to favor the “establishment” candidates.

It’s great to be in Iowa this weekend, the unrivaled capital of the political universe. With two competitive races, the drama is high, the tension palpable. Of course, Iowa has consistently been a bellwether on the Democratic side, but it has far too much evangelical influence to have the same significance for the GOP (Rick Santorum, Mike Huckabee and Pat Robertson are recent winners). That said, a Trump victory over Ted Cruz, the evangelical choice, would be a significant victory for Trump and a bitter loss for Cruz.

Lastly, I wish I could have spent a week in western Iowa to witness Republican candidates—or perhaps even Sanders—campaigning at evangelical churches in January. I’d love to know more about those communities, to discover if I could deeply relate to any of the adults. I’m no fan of American conservative Christianity, but what I find truly appalling is whom the conservative Christians of Iowa vote for. I wonder if their kids are for Bernie?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.