Neoliberalism and the Birth of Big Pharma

Seventy-five years ago in Chicago, a conservative project was hatched to cure classical economics of its aversion to patents and monopolies. The drug companies were its first and biggest beneficiaries. Pills and U.S. currency photo by Adobe.

Pills and U.S. currency photo by Adobe.

The following is an adapted excerpt from Alexander Zaitchik’s “Owning the Sun: A People’s History of Monopoly Medicine from Aspirin to Covid-19,” which was released in paperback this week by Counterpoint.

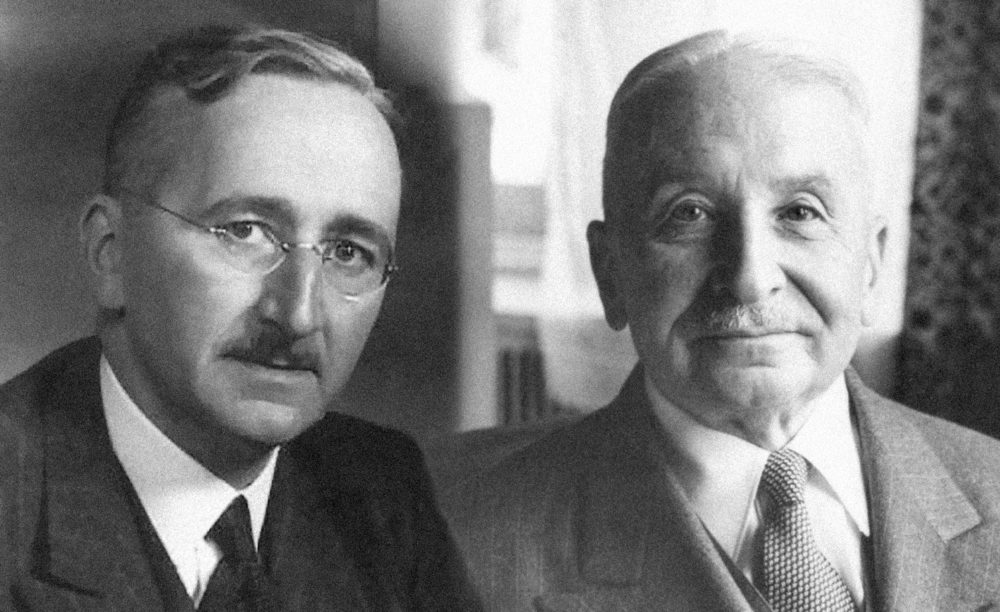

Friedrich von Hayek was already famous within the economics profession when he wrote “The Road to Serfdom,” the 1944 book that made him a global celebrity. During the 1930s, the Austrian-born Hayek had established himself at the London School of Economics as a leading theorist of pricing, monetary policy and business cycles. He approached these subjects with a belief that the market was fundamentally self-balancing and all-knowing. This placed him in conflict with John Maynard Keynes, whose ideas dominated mainstream Western economic thinking before, during and after the war. Hayek’s first public encounter with Keynes occurred shortly after his arrival in England from Vienna, when the two men clashed over government spending in the pages of the London Times. The letter exchange was a preview of their looming transatlantic ideological conflict over the postwar economic order. Until Hayek’s death in 1992, Keynes’s fluctuating influence would serve as a measure of his own; an indicator of Hayek’s value, as the Austrian might have said.

Aspirin to Covid-19

By Alexander Zaitchik

Hayek’s criticism of Keynes reflected the worldview he developed in the 1920s as an acolyte and colleague of his fellow Austrian, Ludwig von Mises, the leading figure in a movement devoted to reviving interest in the classical liberal economics and 19th-century ideas about the minimalist state. Against the distraction of air raid sirens, Hayek expanded on Mises’ ideas to pen a contrarian theory of the rise of fascism. While the prevailing view in the United States and Britain was that fascism was a phenomenon of the right — emerging in response to the threat posed by liberalism, socialism and collectivism to traditional hierarchies — Hayek argued the opposite. For him, fascism was a natural progression of the interventionist state. Priming demand with government spending, providing basic social insurance, attempting to macromanage the economy — all of these were not a bulwark against tyranny, but steps on the “road to servitude,” as Hayek first titled “The Road to Serfdom.” The only guarantor of individual freedom, he believed, was the minimalist state described by the classical and neoclassical economists. Inherently virtuous and self-calibrating market forces alone could stop the future emergence of fascist leaders like Adolf Hitler.

“The Road to Serfdom” sold well in England upon its release in 1944, but it was the U.S. edition, published a year later by the University of Chicago Press, that changed the world.

In April 1945, Hayek was touring the United States promoting the Chicago edition, Reader’s Digest released a condensed adaptation. Overnight, the formerly obscure academic became a household name, and Hayek’s appearances became standing-room only events. One evening early into Hayek’s new fame, he was leaving an event at the Detroit Economic Club when he was approached by a man named Harold Luhnow. The scion of a family manufacturing business in Kansas City, Luhnow was in the process of taking control of the family’s sleepy but well-endowed philanthropic outfit, the William Volker Charities Fund. Luhnow had a vision to fund the dissemination and popularization of classical economic ideas, as well as to sponsor free market scholarship like Hayek’s book. In Detroit, he proposed to Hayek the funding of another Reader’s Digest-style edition of “Serfdom,” written at an even more basic level for a popular U.S. audience. Hayek politely demurred, but wasn’t quite ready to let Luhnow walk away. He countered with an idea of his own: Would the funder be interested in supporting a multi year academic project focused on the great economic questions of the age?

Luhnow assented on the spot. The following autumn, Hayek joined several conservative economists at the University of Chicago to launch a five-year study program called the Free Market Study.

This was the first step in creating an apple-pie version of classical liberalism — one that featured major ingredients not found in the original Austrian strudel. The Chicago School, as it became known, quickly developed a tolerance, and then an affection, for cartels, monopolies, and — reflecting the quiet supporting influence of the drug industry — patent-based monopolies above all. A multidisciplinary laboratory cosponsored by the university’s law school, business school and economics department, had nurtured Hayek’s baby into a new kind of liberalism.

In a word, neoliberalism.

* * *

The Free Market Study tackled a number of economic and ideological problems. Among them was reconciling the 19th-century theory of the minimal state with the modern realities of economic concentration, cartelization and monopoly.

For classical economists, monopolies and cartels were the inevitable products of modern industrial economies, and thus forced upon them a difficult choice. Option one: violate a core tenet of classical theory and accept concentrations of corporate power that suppressed “natural” price movements and caused a number of other anti-competitive distortions. Option two: permit the state to develop and deploy regulatory powers, a risk of expanding the state that could be justified on the grounds that strong laws and regulatory agencies alone could protect a functioning free market.

There was no third option.

Ludwig von Mises, Hayek’s mentor and father of the Austrian School, chose intervention. So, too, did his most influential students and colleagues, notably Hayek, Arnold Plant, Fritz Machlup and Michael Polanyi. As a group, Austrian School liberals supported antitrust laws and their enforcement by the state. Since patents represented a form of state-protected monopoly, they proposed a uniquely simple and elegant solution: abolish them.

adamantly opposed to patents and other forms of knowledge monopoly. Photo: IHSF

Intellectual property claims were also at odds with how the Austrians understood the flow of knowledge in a free society. Patents, wrote Hayek’s colleague Michael Polanyi in 1944, “parcel up a stream of creative thought into a series of distinct claims, each of which is to constitute the basis of a separately owned monopoly. But the growth of human knowledge cannot be divided up into such sharply circumscribed phases . . . Mental progress interacts at every stage with the whole network of human knowledge and draws at every moment on the most varied and dispersed stimuli. Invention is a drama enacted on a crowded stage.”

Hayek’s theory of the economy as a giant information processor also left little room for patents. The healthiest economy was the one that most efficiently facilitated the natural flow of knowledge. “If the economy is knowledge before it is property, then the question of how much of that knowledge should be made into property is of critical importance,” writes economic historian Quinn Slobodian. “It follows that if you privatize too much or incorrectly, knowledge could also be misallocated, blocked or left stagnant.”

The evil of patents was a recurring theme during 10 days of meetings convened by Hayek at the Mont Pelerin mountain resort overlooking Lake Geneva in April 1947. It was there that Hayek and 39 like-minded scholars first developed and codified a critique of collectivism that had no place for monopolies on knowledge. “A slavish application of the concept of property as it has been developed for material things has done a great deal to foster the growth of monopoly,” said Hayek. “Here drastic reforms may be required if competition is to be made to work.”

One member of Hayek’s audience had especially strong feelings on intellectual property. In 1934, University of Chicago economist Henry Simons had published a pamphlet, “A Positive Program for Laissez Faire,” regarded at the time as the definitive statement of the classical case against patents. “The great enemy of democracy is monopoly, in all its forms,” wrote Simons. The political ends of economic policy were threatened unless the state acted against monopolists to preempt “a domination of the state by them.” In later works, Simons extended this critique to the state’s “shameful” allowance of “gross abuse of patent privilege for extortion, exclusion and output restriction.” In the assessment of historian Robert Van Horn, “Simons condemned the patent system because it enabled firms to restrict competition [and] augment their monopoly power. Just as free trade required equal and free access to markets, industrial research required equal and reasonable access, if not wholly free access, to technical knowledge.”

Simons’s view was shared by the Hayek-led group that launched the University of Chicago’s Free Market Study in 1946. Indeed, these views were shared by every major European and American conservative intellectual at the time, including a University of Chicago economist named Milton Friedman.

As a group, Austrian School liberals supported antitrust laws and their enforcement by the state.

Only one figure associated with the project dissented from this key tenet of classical orthodoxy. He happened to be the one holding the checkbook.

* * *

Harold Luhnow could not claim ignorance of the Austrian School position on patents and monopolies. The Reader’s Digest edition of “Serfdom” included Hayek’s general views on patents and concluded with his warning that “great danger lies in the policies of two powerful groups, organized capital and organized labor, which support the monopolistic organization of industry.”

For American conservatives like Luhnow, the Austrian fear of “organized capital” was disposable. A product of European trauma, maybe, a bias based on an understandable obsession with industry’s role in Imperial and Nazi Germany. But big business was not a threat here, not in America. Their political destination was not 19th-century Holland — which rejected patents in favor of a “free trade in inventions” — but Gilded Age Pittsburgh, where titans not only had a God-given right to patents, but could do with them what they goddamn pleased. The conservative revival they envisioned had no place for valorizing the antitrust crusade of Thurman Arnold, Roosevelt’s antitrust chief, who continued to haunt corporate America’s nightmares.

Months before the Free Market Study was to begin, an unexpected event released the tension in Chicago between classical liberal theory and modern American conservatism — and released it in Luhnow’s favor. In June 1946, Henry Simons committed likely suicide by overdosing on barbiturates. A key figure in the development of monetarism and generally considered the most brilliant of the Chicago conservatives, Simons was the Chicago group’s antitrust conscience. He did not apologize for advocating the use of state power to maintain the preconditions for a free market, and once described the Federal Trade Commission as the most important government agency. Heterodox but consistent, he hated Hoover as much as Roosevelt, and oligopolies and monopolies above all.

Luhnow understood Simons’s views as well as the respect he commanded from the Chicago group’s members, many of whom had been influenced by Simons’s strict 1934 Austrian tract, “A Positive Program for Laissez Faire.”

Following Simons’s death, Luhnow asked his friend and fellow Chicago economist Aaron Director to take over running the Free Market Study. In his book “Goliath,” Matt Stoller writes that Luhnow had been concerned with Simons’s influence and believed Director to be “far more ideologically malleable”— especially on the subject of patents.

paved the way for the neoliberal

embrace of patents and monopolies.

Credit: Wikipedia

For the next three years, not much changed, and Director maintained the Simons-Hayek line on monopoly, which aligned with the views Director expressed in an address to the 1947 meeting in Mont Pelerin. Current antitrust laws, he said, should be seen as “stopgap measures” on the way to more radical restrictions on corporate power. These included limits to the scope of corporate activity as well as “perhaps a direct limitation of the size of corporate enterprise.” Director was equally clear in his condemnation of patents as the handmaidens of monopoly and called for dramatic reductions in their terms. Simons would have been proud.

Only when funding for the Free Market Study was set to expire, in late 1950, did Luhnow, the funder behind the project, begin to express himself on the matter. According to historian Rob Van Horn, officials from “the Volker Fund went so far as to threaten to eject Director from his leadership role in the project because the Volker Fund refused to accept certain tenets of classical liberalism, namely, those espoused by the deceased Chicago economist Henry Simons.”

The evidence suggests Director received the message loud and clear. Later that year, Director began a steep public climbdown from his former, ideologically consistent opposition to monopoly. In a 1950 book review, Director argued that monopolies no longer justified state intervention because the “corroding influence of competition” was their natural enemy and could be counted on to “destroy” concentrations of economic power. If the market produced monopoly killing antibodies, then antitrust enforcement and patent reform were unnecessary. The suggestion that “concentrations of business power were relatively benign,” writes Van Horn, marked a break from Director’s influence and signaled the group’s impending revisionism of classical liberal doctrine.

For American conservatives like Luhnow, the Austrian fear of “organized capital” was disposable— a product of European trauma.

At a Chicago conference on corporate law the next year, Director unveiled a more detailed version of his new beliefs. “The corporate form was ideal,” he said, “because it did not contribute toward business monopoly.” That which emerged from the market was by definition a natural expression of the market, and thus inherently less threatening than any form of government coercion.

* * *

When the Free Market Study expired in 1952, its principal figures had begun the process of moving toward an accommodation with the new doctrine of benign monopoly. They would soon accelerate the process of this accommodation, with a little help from Luhnow. Indeed, doing so was the focus of the next Luhnow-funded project at the University of Chicago, launched in 1952, called the Antitrust Project.

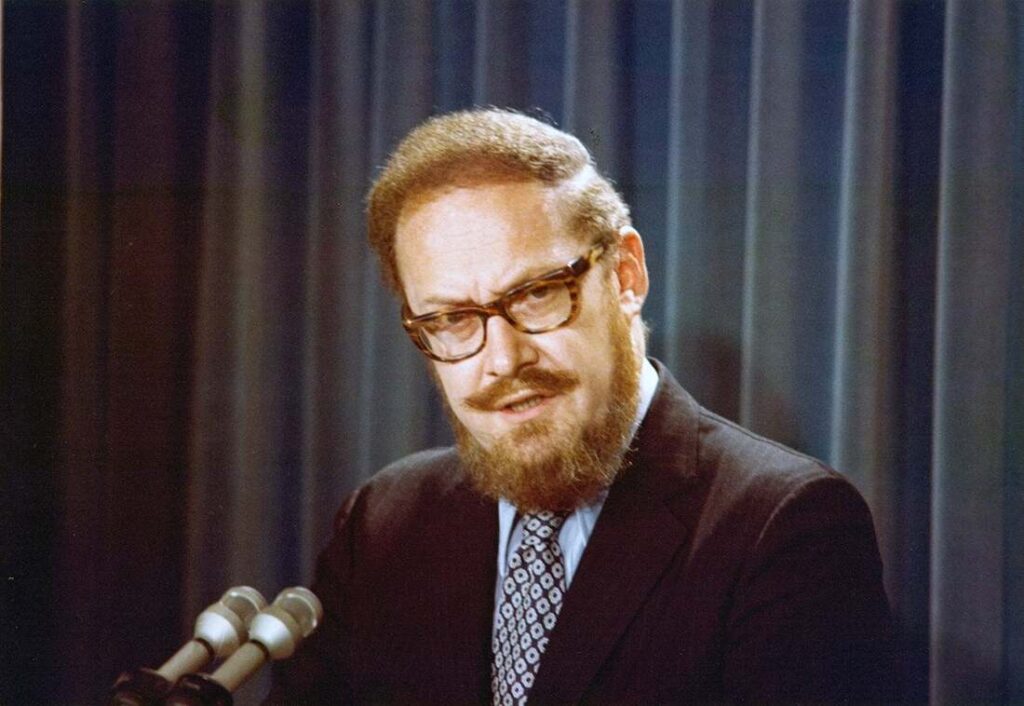

The purpose of the Antitrust Project was to interrogate and revise the traditional American aversion to monopoly and the antitrust movement that gave it expression. Over the next several years, the Project produced a multivolume revisionist history of antitrust that reversed conventional legal and economic thought on the subject. The Project’s breakout star was a young Chicago legal scholar named Robert Bork. A talented writer and polemicist, Bork would go on to produce a prodigious number of reappraisals of the Sherman Antitrust Act and related case law. His defenses of the legality and competitive advantages of vertical mergers were as fulsome as his condemnations of antitrust actions were withering.

Not to be outdone, Director produced articles targeting even the most celebrated, least controversial antitrust suits in the country’s history. These included the 1911 Supreme Court decision that dismembered Standard Oil, a judgment dismissed by Director as without merit and counterproductive. In a 1956 Project article that anticipated later theories about shareholder value, Director and Chicago law school dean Edward Levi argued that corporations benefited the wider economy when they used exclusionary practices to increase their market power. Originating in the market, these practices were also expressions of the market. They were, by definition, good; should not be constrained in any way, including antitrust action.

history of America’s antitrust traditions. Photo: The Bork Foundation.

Hayek did not join his colleagues in this sharp ideological turn. He spent 1959, his last year in Chicago, writing a book that contained a forceful restatement of the Austrian School’s traditional opposition to patents and all forms of monopoly. “Knowledge,” Hayek wrote in “The Constitution of Liberty,” “once achieved, becomes gratuitously available for the benefit of all. It is through this free gift of the knowledge acquired by the experiments of some members of society that general progress is made possible, that the achievements of those who have gone before facilitate the advance of those who follow.”

The business interests that opposed Roosevelt and hailed Hayek’s book never had any intention of adhering to the Austrian’s consistent objection to patents, monopolies, and other forms and enablers of concentrated power. Once Luhnow’s Chicago investments had paid off by revising core tenets of Hayek’s liberalism in an American image, the next step was to take the resulting ideology for a road test.

* * *

For years after the launch of the Free Market Study, the drug companies didn’t pay much attention to the arcane intellectual experiment at the University of Chicago. This changed around the time a Democratic senator from Tennessee named Estes Kefauver announced he would hold extensive investigative hearings on the postwar drug industry. The passage of a drug industry reform law three years later confirmed both the threat the industry faced and the limits of its dated Cold War-meets-Chamber of Commerce political strategy. With the expansion of Food and Drug Administration powers in 1962, the industry’s product chain had come for the first time under the purview of a government agency. At best, the new regulations threatened future drug rollouts; at worst, they were a first step toward the harsher controls and restrictions sought by Kefauver protégés like Wisconsin Democrat Gaylord Nelson.

The Chicago figure who took the greatest interest in the drug industry was a relatively late arrival to the Antitrust Project. George Stigler joined the Chicago economics faculty from Columbia University in 1958. Like his new colleagues, Stigler had completed the journey from classical liberal orthodoxy — he too was once a devotee of Henry Simons — to the neoliberal version that alienated the departing Hayek. In 1942 Stigler published an anti-monopoly treatise that echoed Simons’s endorsements of Thurman Arnold’s antitrust division. In a 1945 speech to the American Economic Association, Stigler called monopoly “an evil demanding correction.” The case for limiting the terms of patents, he said, “is surely irrefutable.”

When Stigler took up the subject of regulation in the late 1950s, he made a close study of the drug industry’s travails with Congress and the FDA. This work led him to develop the concept for which he is best remembered: “regulatory capture.” Stigler argued that because the industries targeted by regulation have bigger stakes in policy than the public that is invoked to justify the regulations, well-financed corporations will inevitably end up controlling the regulatory agencies to their advantage. One obvious solution to this would be increasing democratic oversight and regulation. But Stigler, like his new colleagues at Chicago, was no fan of democracy. In her book, “Democracy in Chains,” Nancy MacLean quotes Stigler telling a 1978 meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society that if conservatives wished to avoid becoming a “permanent minority,” they should start seeking “political institutions and policies that allow us to pursue our goals,” including “the restriction of the franchise to property owners, educated classes, employed persons or some such group.”

By 1952, the principal figures in Chicago had begun moving toward an embrace of patents and a belief in “benign monopoly.”

The other solution to regulatory capture was the one Stigler’s friend and colleague Milton Friedman advocated in his weekly Newsweek column: abolish the agencies and leave regulation to consumers and the market. Stigler thought this radical position useful in chumming the waters of public backlash against the activist state, but ultimately unrealistic and crude. Above all, abolishing the agencies was unnecessary. Historian of economics Edward Nik-Khah writes in his study of Stigler that the economist believed there existed “several ways to skin a cat.” As chair of the University of Chicago Business School’s Governmental Control Project, and later his own fiefdom, the Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, Stigler theorized how industries could go about skinning their particular regulatory cats. His conclusions led him to theorize how corporate America could mentally colonize the agencies and the public without their even knowing it. “What began as a study of the nature and extent of governmental control of the economy came to explore methods for how to control the government,” writes Nik-Khah.

Stigler’s theories were initially precision-engineered to help one industry in particular: pharmaceuticals.

To the drug industry, Stigler’s blueprints for a long-term stealth attack on the organs of popular government seemed visionary. Stigler would show the companies how to control their destiny not by condemning the FDA as socialistic, or underwriting libertarian editorials calling for its abolition, but rather by shaping the thinking and priorities of FDA administrators and scientists, politicians and the public. The goal was cognitive capture, not regulatory capture.

For the drug companies, this opened up a number of new fronts. They could support Robert Bork’s revisionist attacks on the histories of antitrust law and patent populism; underwrite closer relations with research scientists; and fund quasi-academic research centers to produce papers and books. These same centers could also serve as “echo chambers” (a new term) to ensure the industry’s messages rang continuously in the public square. Slowly but surely, Stigler argued, these messages would be internalized and repeated by the agency.

* * *

In 1971, a group of senior Pfizer executives visited Hyde Park to meet with the dean of the University of Chicago law school, Phil Neal. Like other companies with an interest in regulation, they were curious to know what funding opportunities existed to support the work of Stigler and others in what had become known as the Law and Economics movement. Its biggest corporate funder at the time was General Electric, sponsor of the school’s Government-Business Relations program as well as the work of Robert Bork, who spread his antitrust revisionist gospel in courtrooms and boardrooms across the country, in a tireless crusade to make the world safe for monopoly.

If the Pfizer executives debriefed the law school dean about the enemies at the drug industry’s gate, it was likely a long meeting. In 1967, Wisconsin Democrat Gaylord Nelson picked up Kefauver’s mantle in the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly and initiated ongoing hearings on “Competitive Problems in the Pharmaceutical Industry.” He also revived Kefauver’s mission to reduce the scope of drug monopolies, and proposed a law requiring the prescription of generic drugs over their branded and more expensive counterparts. Then there was the rising force of a national consumer rights movement, led by a young lawyer named Ralph Nader.

The Nixon administration, meanwhile, was also considered antagonistic to the drug industry. In 1970, a deputy attorney general in the Justice Department issued a “watch list” of nine patent and licensing practices that would be prosecuted as anti-competitive restraints of trade. In 1974, another of Nixon’s assistant attorney generals declared private patent claims on government inventions “unconstitutional,” a view seconded in a recent federal court decision.

Stigler’s theories about regulation and monopoly were precision-engineered to help one industry in particular: pharmaceuticals.

This was the backdrop to the two-day Conference on the Regulation of the Introduction of New Pharmaceuticals hosted by the University of Chicago law school. During the first week of December 1972, professors affiliated with the Law and Economics movement delivered critical talks on regulation and the 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments, followed by drug company executives and corporate research directors who delivered papers of their own. The presentations reinforced each other, producing a braided noose they used to intellectually hang FDA regulations for the crimes of being unnecessary and counterproductive.

The arguments were not scientifically sound, or the products of rigorous scholarship. When the talks were collected and published as a book, “Regulating New Drugs,” it was roundly panned in the scientific press by reviewers who seemed baffled by recommendations that, as one reviewer put it, “are so at variance with the current thinking in this field that they will be subject to much criticism.” These reviewers did not understand that establishing a counternarrative at “variance” with dominant thinking was the entire point of the conference, as it had been of the Chicago School and the Law and Economics movement for decades.

* * *

At Stigler’s conference, the drug executives and academics reconsidered the industry’s longstanding media strategy to discredit or change the minds of liberal senators, federal regulators, the consumer rights movement, antitrust officials and the public. Alumni of the Chicago conference would not, as in the past, fan out to plant red-baiting editorials in newspapers and magazines. Instead, they proceeded to establish an industry funded pseudo-scientific echo chamber designed to rewire the terms of debate and “co-opt the experts with finesse,” in the words of an influential Stiglerean tract published in 1978 called “The Regulation Game.”

In 1974, conference participants founded the first industry-supported think tank devoted to drug policy, the Center for Health Policy Research at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. Two years later, another participant, the clinical scientist-turned-FDA critic Louis Lasagna, founded the Center for the Study of Drug Development at the University of Rochester. Both centers produced research that was designed to shift the drug and patent debates. Success came quickly. One of the first memes these factories produced was the “drug lag.” This was the idea that excessive safety regulations were actually hurting public health because they deterred investments in research and delayed the arrival of new drugs on the market. As Daniel Carpenter notes in his history of the FDA, the notion that regulations stifled innovation quickly took root in public and academic debates, helped along by pseudo-academic papers, underwritten by Pfizer, started to appear as citations in scientific and economic journals.

1970s, helping to create the industry we know today. Photo: Stigler Center.

Following Stigler, the think tanks did not simply put the “regulation versus innovation” theme on endless repetition. Scholars affiliated with the Chicago-born network constantly finessed the message with variations on the idea that patents alone drive and accelerate innovation. The genre reached a rhetorical crescendo in 1996 with Michael Novak’s Pfizer-funded philosophical essay on the moral and godly bases of patent monopolies, “The Fire of Invention, the Fuel of Interest.”

Half a century after this echo chamber hatched from an industry-academia networking and strategy event, it continues to shape and police the boundaries of the drug pricing debate, awaiting activation at key moments. In the early 2000s, the system released the meme of the “$800 Million Pill,” cited by George W. Bush as a justification for signing away the government’s right to negotiate drug prices in the 2003 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act.

The drug industry network built in the mid-1970s — one able to produce propaganda, reinforce narratives, and send both reverberating through the wider culture — served as a model for the tobacco and fossil fuel industries, who faced similar regulatory and political threats related to their impacts on public health. Oil companies were especially precocious students of Stiglerian ideas about co-opting experts with funding. Following a 1969 oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, state agencies were dumbfounded when every local scientist with relevant expertise refused to testify against the companies, because every one of them was being funded in whole or in part by the industry.

In the name of science, the echo chamber has learned to effectively attack data wielded by its critics as “adversarial” and thus fundamentally unserious.

“The point of pharma’s echo chamber was never to get the public to support monopolistic pricing,” says Nik-Khah. “As with global warming denialism, which involves many of the same institutions, the goal was to forestall regulation by sowing confusion about the relationship among prices, profits, innovation and patents.”

“Stigler and those influenced by his work had very sophisticated ideas about how to audit and slowly take over the agencies by getting them to internalize [their] positions and critiques,” continues Nik-Kah. “You target public conceptions of medical science. You target the agencies’ understanding of what they’re supposed to do. You target the very thing inputted into the regulatory bodies — you commercialize science.”

Perhaps the most Stiglerian tactic of them all was a trend that emerged following the Chicago economist’s death in 1991: industry-funded academic chairs in bioethics.

Another key characteristic of the neoliberal project — its obsession with “objective” cost-benefit analysis — was observed as far away as France. In a lecture series delivered in 1978 and 1979, later published as “The Birth of Biopolitics,” philosopher Michel Foucault described the defining characteristic of U.S. neoliberalism as a campaign of “permanent criticism of governmental policy.” The heart of all neoliberal analyses, he told the College of France, was the use of self-interested deployment of cost-benefit analysis to

test government action, gauge its validity, and to object to activities of the public authorities on the grounds of their abuses, excesses, futility, and wasteful expenditure . . . [It targets] the activity of the numerous federal agencies established since the New Deal and especially since the end of the Second World War, such as the Food and Health Administration [sic].

Foucault delivered this speech in March 1979. Later that year, the project he described would near its endgame in Washington, D.C., where Stigler and his colleagues became honored guests of a new U.S. president. Eight years later, Ronald Reagan would nominate Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, a half century after Harold Luhnow initiated a Midwestern lobotomy on Austrian liberalism, removing the pesky lobe that allowed Hayek to go to his grave opposing patents as the handmaidens of monopoly and other unhealthy forms of concentrated power.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

The American for-profit healthcare system:

Any pre-1973 "for-profit" medical healthcare entities could not compete with the community funded healthcare. Nixon did a personal favor for his friend and campaign financier, Edgar Kaiser, then president and chairman of Kaiser-Permanente. Nixon signed into law, the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 (HMOA73), in which medical insurance agencies, hospitals, clinics and even doctors, could begin functioning as for-profit business entities instead of the service organizations they were intended...

The American for-profit healthcare system:

Any pre-1973 "for-profit" medical healthcare entities could not compete with the community funded healthcare. Nixon did a personal favor for his friend and campaign financier, Edgar Kaiser, then president and chairman of Kaiser-Permanente. Nixon signed into law, the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 (HMOA73), in which medical insurance agencies, hospitals, clinics and even doctors, could begin functioning as for-profit business entities instead of the service organizations they were intended to be.

HMOA73 called for the states to decertify and close all community-based hospitals this was to limit the number of hospital beds within an HMO’s coverage area. For the most part America's healthcare, before 1973, was community funded services with excellent care at a minimum cost to the public.

HMO doctors were deterred from curing illnesses, no profit in that. But doctors were encouraged to force people to endure repetitive doctor visits, endless (often useless/redundant) tests, and the ever-increasing costs of prescription drugs, all provided within the HMOs.

Since 1978, there have been yearly increases in the costs all sectors of healthcare. Those increases rose when the greed and hubris of the 1% was unleashed as profits soared. More healthcare costs were put over onto premium-holders with the introduction of deductibles and co-pays. The “for profits” bottom lines were “cleaned” with the invention of pe-exiting conditions and limits on lifetime healthcare, single premium healthcare, and old-age healthcare, without exceptions for the time the person had been paying premiums. The more profitable bottom lines made it easier for upper-echelon employees to ask for and get outrageous salary raises each year.

The Affordable Care Act was meant to limit all that greed and hubris by mandating what the companies paid out of premiums taken-in. The A.C.A. mandated an 80%/target for actual premium holders’ medical expenses paid out and a 20% limit on company expenses paid-out from premiums paid in and that was to eliminate the outrageous salary increases by eliminating all the “greed and hubris” listed above.