|

To see long excerpts from “My Age of Anxiety” at Google Books, click here.

|

“My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind”

A book by Scott Stossel

Some years back I picked up the biography of Sargent Shriver, written by a journalist named Scott Stossel. I knew something about Shriver, a larger-than-life character who launched the Peace Corps, Head Start and Legal Services for the Poor. About Stossel I knew nothing, except that he looked mighty young to have written such a big book. It turned out my skepticism was misplaced. It was a marvelous biography, and one I read with care, as it related to a writing project of my own. At the time I wasn’t particularly satisfied with my efforts, and so while I certainly enjoyed Stossel’s book, I was also hit with pangs of envy. His writing was fluid, his research deep. This man had mastered his material.

The Stossel of my imagination — cool and calm, approaching challenges without a hint of uncertainty — is nowhere to be found within the pages of his second book, “My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind.” Sure, the author photo shows him grinning, and the jacket flap notes that he is the editor of The Atlantic and has written for publications that include The New Yorker. But crack open the book, and you’ll learn that Stossel is a nervous mess. In therapy since the age of 10, he suffers from a wide range of phobias, from the common (public speaking, flying) to the less so (cheese, vomiting). He’s tried meditation, hypnosis and something called interoceptive exposure therapy. He’s done acupuncture, yoga, massage and prayer. He takes medications, lots of them, sometimes combined with alcohol. Yet for all his efforts — and it’s clear that Stossel has put in the work — he is by no means cured. It’s not quite right to call this a pessimistic book, but it’s certainly not one with a happy ending.

As a young boy, whenever Stossel’s parents left the house, he was sure they would never return, believing that they had either perished in a car crash or simply decided to abandon him. As an adult he can’t travel far from home without his stomach beginning to churn and his bowels loosening. He describes a memorable episode on Cape Cod, while researching the Shriver biography, when he plugs up a toilet while at the vacation house of the extended Kennedy family. He sops up the ankle-deep mess as best he can and scurries toward his room, drenched in panic sweat and wrapped in a filthy towel. It is then that he crosses paths with John F. Kennedy Jr. “What I was feeling,” he writes about the episode, “was not, strictly speaking, anxiety; rather, it was a resigned sense that the jig was up, that my humiliation would be complete and total.”

Understanding this fundamental aspect of anxiety — the fear of being revealed — highlights the bravery of Stossel’s book. Sufferers of anxiety often compound their anxiety by worrying that other people will notice that they are anxious. To compensate, they often adopt false airs of confidence and competence, working extremely hard to hide how they are feeling. By all accounts — at least when not suffering breakdowns in private — Stossel has managed to project the image of a very calm man. One former colleague calls him “human Xanax” for his ability to step into a tense room and chill everyone out. But with his new book, Stossel demolishes this carefully constructed self-portrait — which he has been touching up for decades — and replaces it with something more honest, more human, and much less flattering. “I have since the age of about two,” he writes, “been a twitchy bundle of phobias, fears, and neuroses.”

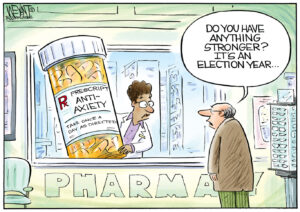

Why are some people prone to anxiety? Does medication help? Is therapy effective? And what, exactly, is anxiety? These are some of the questions that Stossel grapples with, often using his personal battles as a jumping off point, and while he’s a deep reader and dogged researcher — he seems to have sucked up and digested every study published on the topic — it is rare for clear answers to emerge. Take selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, for example, the most widely prescribed class of drugs for anxiety and depression. SSRIs include Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft and Celexa. Millions of people — including Stossel — swallow them daily. Yet, it turns out, there is not much hard evidence that they actually work. When the British Medical Journal reviewed the literature, it determined that SSRI drugs “do not have a clinically meaningful advantage over placebo.” Even Arvid Carlsson, who originally postulated that depression was linked to low levels of serotonin — which SSRIs are designed to counteract — has backed away from his original claims.

Stossel continues to take an SSRI, but can’t say with any certainty that it makes him feel better. I have also taken various SSRIs over the years, and while I initially took great comfort in the idea that the medication was helping, and, perhaps more importantly, that I was finally doing something more than trying to ignore my anxiety, it’s feasible that the benefits were mostly psychological. Now off medication for several years, I feel about the same as I did while on it. At least I think I do, most days. Anxiety is a swampland where it’s hard to gain enough solid purchase to say anything with much confidence.

Stossel proves to be a steady guide through this swampland, serving as an honest referee to the bitter fights playing out between proponents of various theories (meds vs. no meds; talk vs. behavioral therapy, etc.). Although much about anxiety remains unsettled, there is mounting evidence that genes play an important role. Here, Stossel has been dealt quite a hand. Once he starts investigating his family tree, it’s hard to find any branches that are strong and healthy. His sister, Sage, suffers from debilitating social anxiety. (A cartoonist, she recently published a graphic novel about a super-heroine who gobbles Xanax.) His great-grandfather, a Harvard dean, was forced into early retirement, undergoing electric shock therapy and institutionalization before descending into a semi-comatose state. Stossel’s own young children have already entered therapy, exhibiting the extreme separation anxiety (son) and fear of vomiting (daughter) that their father has battled throughout his life. He dedicates the book to his children — “may you be spared” — but this is wishful thinking.

Many are not spared: Nearly one in four Americans has an anxiety disorder, making it the most common mental illness in the United States. And we’re in pretty good company: Our ranks include the likes of Charles Darwin, Emily Dickinson, Sigmund Freud and Thomas Jefferson (who was so afraid of public speaking that he gave only two public speeches during his presidency). Anxiety has the singular ability, as psychiatrist Barry Wolfe puts it, to “paralyze action, promote flight, eviscerate pleasure, and skew thinking toward the catastrophic.” But it can also make people more sensitive, careful and diligent. As Stossel’s wife asks, “What if you’re cured of your anxiety and you become a total jerk?”

He writes, “My anxiety can be intolerable. It often makes me miserable. But it is also, maybe, a gift — or at least the other side of a coin I ought to think twice about before trading in.” To call it a gift is going too far. If Stossel could trade his anxiety in, I don’t think he would think twice, and neither would I. But it is what we have, and what many have, and it can grow only stronger if we pretend it doesn’t exist, or think it reflects some deep personal failing that must be hidden at all costs. This is, unfortunately, what many people do. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America reports that more than one-third of people with social anxiety suffer with symptoms for over a decade before seeking treatment. That’s a long time to spend living in a private hell without a supportive shoulder to lean on. And so although Stossel has written an engaging and serious book — often hilarious, occasionally heartbreaking — its greater value is in the personal courage he is able to muster and model.

“Maybe finishing this book and publishing it — and, yes, admitting my shame and fear to the world — will be empowering and anxiety reducing,” he writes. I hope the book plays that role for Stossel. I have no doubt it will for many readers.

Gabriel Thompson has written for The New York Times, New York, The Nation and Mother Jones. His most recent book is “Working in the Shadows: A Year of Doing the Jobs (Most) Americans Won’t Do.”

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.