Mr. Fish in Conversation With Paul Krassner: The Politics of Being a Smartass

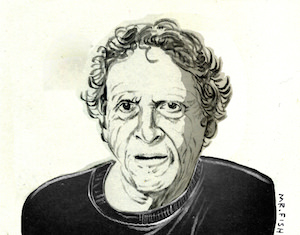

Paul Krassner, the editor of what writer Terry Southern said was "the first American publication to really tell the truth," has been called the father of the underground press He has also been called a lousy motherfucker by his establishment detractorsPaul Krassner has been called the father of the underground press.

Paul Krassner, a founding member of the Yippies, a Merry Prankster and the editor of what writer Terry Southern said was “the first American publication to really tell the truth,” The Realist, has been called the father of the underground press. He has also been called a lousy motherfucker by his establishment detractors, an addendum that, if true, calls into question the genetic integrity of the children that he is purported to have fathered, which are typically depicted as cross-eyed and babbling and groping at their groins in total disregard for whoever might be watching. Of course, when it comes to creation myths all over the world and the grotesquely unflattering depictions of every mother made to appear in each — whether they are virgins, a discarded rib or a duplicitous and distrustful moon — most people are encouraged by Krassner’s relentlessly infectious curiosity about how and why the American culture dysfunctions so well, so much so that they are more than willing to ignore the details of the underground press’ inception and to simply marvel at the multitudinousness of the father’s offspring.

Not only that, but there is something to be said for getting to bear witness to the blessed miracle that, at 80, Krassner is still writing books and articles that continue to influence the best and the brightest hell-raisers among us. His new book is an updated and expanded version of his wily classic memoir, “Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counterculture.”

What follows is a portion of a conversation that I had with him at his home in Desert Hot Springs, Calif., one morning in May, while lizards baked euphorically on the sidewalks outside, the odorless hot springs for which the town is famous percolated through the dry earth all around us and the ruddy piquant of slow-burn marijuana made the air as festive as if christened by a flatulent Christmas tree ablaze with good cheer.

***Fish

: Because you have smoked pot with, interviewed and/or published so many of the most important and influential thinkers and artists of the mid-20th century, I thought it might be smart to get your perspective on why, when it comes to contemporary culture, artists and writers and poets and painters and social philosophers, either by accident or by deliberate design, have been removed from the national debate about who we are as a species and where we are going as a society.

Krassner: I’m going to have to plead the Fourth [the amendment that guards against unreasonable searches and seizures] on that.

Fish: Well, let me give you an example about what I mean. Besides the obvious superstars of the time, people like [Lenny] Bruce, [Marshall] McLuhan, [Norman] Mailer, [John] Lennon, [Mort] Sahl, you also had television personalities like Millicent Martin in 1963 on “That Was the Week That Was” singing a song, dressed as Uncle Sam, called, “I Want to Go Back to Mississippi,” which contained the lyric:

Where the Mississippi mud Kinda mingles with the blood Of the niggers who are hanging From the branches of the trees

Krassner: Wow.

Fish: There’s even a refrain that describes a ” … butter-colored moon” and “cutting up a chocolate-colored koon.” Now, what’s remarkable about that is how brutally frank the social commentary was delivered and how bluntly the satire was played and how it was broadcast on mainstream television. Remember, this was not a nightclub or some underground cabaret somewhere — it was on the BBC.

Krassner: Well, I did recently see a repeat of something from “MADtv” — it was a sketch where there was a group of black actors who were all dressed as pimps waiting at an audition. It was a takeoff of the old Snickers bar commercials, but instead of saying Snickers the announcer says, “Gonna be here for a while? Have a Snigger’s bar.”

Fish: That’s different, though. That’s more like a parody that addresses the laziness of the culture and the inability of decent society to acknowledge the broader implications of racism in general, whereas the piece on “That Was the Week That Was” pointed a very direct finger at how ugly the prejudice is able to manifest itself in very specific acts of race-based violence within American society. In fact, the song states clearly ” … If you ain’t for segregating white folks from the black, then they won’t hesitate to shoot you bravely in the back.” In other words, [the “Week That Was” segment] handles the issue with much more seriousness instead of merely playing it as farce.Krassner: I think Dave Chappelle does more of what you’re talking about.

Fish: Maybe, but [he does it] in an atmosphere much less open to the free expression of ideas. That’s my point. When you’ve got the management at the Laugh Factory [in Hollywood] fining performers for saying the N-word, then the bar is lowered on what qualifies as dissent and what passes for social criticism. When there is nothing but debate surrounding how you should be allowed to say something, then there never comes a time when the content of what you actually say is assessed. That’s when words become meaningless and language becomes a deterrent to knowledge.

Krassner: You’re right. I remember when George Carlin was asked why he didn’t include the word nigger as one of the seven words that you can’t say on TV and he said that there was nothing funny about it. He wanted to maintain what was humorous about the repression of certain words by religious fanatics who believed that bodily functions and sexual activity was taboo. That, he said, is funny as shit.

Fish: Then, I guess, the conversation becomes one about technique and different modes of teaching and sharing information versus just content. Making your ideas interesting enough to make somebody else want to repeat them to somebody else who will then want to repeat them to somebody else, over and over and over again, is how real education and real social change happens. [To] Carlin’s point, jokes are probably repeated more often than dark satire because people prefer laughter over something ugly and depressing that leaves you staring at the wall and feeling hopeless.

Krassner: Of course, to speak to your point about the state of satire today, which I think is where you were going with all this, is that so much of what passes for satire nowadays isn’t real satire, at least not in the traditional sense. For one thing, it isn’t even ironic — it’s Sarcasm 101. Audiences will applaud for name-calling as a replacement for wit.

Fish: I agree — real satire begs a conversation to happen after the joke has been told. Not only that, [it] assumes that a conversation had been going on previous to the telling of the joke. [Satire] assumes that the audience is there to do at least half of the heavy lifting when it comes to getting the punch line and recognizing the irony or the hypocrisy of whatever is being lampooned.

Krassner: And that’s the subjective side of humor, all that [foreknowledge] that makes satire work. There are a lot of factors to consider when building strong satire. But there’s also the objective side [of humor] that, if you can get it in with the subjective side, it really makes for [a good joke].

Fish: The difference between a clown eating a shit sandwich for no reason and the pope eating a shit sandwich for some reason.

Krassner: Yeah. In 1978 I went with my daughter, Holly, to Ecuador on a shamans and healers expedition and we stayed with primitive Indians and took Ayahuasca — I should say indigenous Indians because they looked at us as if we were the primitive ones. Anyway, we lived for a while with three generations of Chiapas Indians. There were about 15 people in our group and one of them was an anthropologist but after a while it became clear that we were the subjects and [the Chiapas] were the anthropologists. I remember watching a mother who was talking to us and how she was playing with her naked son’s penis and how there was no internalization of inhibited social structures, at least none that I could relate to. [Similarly], they would watch us brushing our teeth or doing tai chi and wonder what the hell we were doing, you know. It was peculiar to them, like we were Martians who had dropped out of the sky. Regardless, I had these bright green sunglasses and I let everybody try them on and they all laughed at each other because [the visual] had elements of incongruity. They didn’t know our language, but they knew what they felt in their gut, which was that it was silly. So, while so much of American humor has a lot to do with taste and so much satire has an agenda that serves either the right or the left, there’s a primal sense of humor that resonates with people because it transcends culture and is universal [to everybody].Fish: Right, that’s the appeal of slapstick, I guess. Maybe it’s even the appeal of much of commedia dell’arte, stereotypes being much more closely related to our lower base functions [than our higher]. Still, what scares me is how society can sometimes misconstrue the ease of experiencing that primal sense of humor you mentioned as being the only genuine humor there is and, therefore, the only humor we should recognize. Way too often I hear pundits complaining that satire, like “The Daily Show” or The Onion or “South Park,” is not real humor because it parodies political grandstanding and hate speech and religious buffoonery, that sort of thing. In other words, I’m uncomfortable when the definition of humor excludes irony and critical thinking and dissent because it is assumed that people are way too stupid to get the joke. I hate the notion that laughter cannot be used as a teaching tool and that censorship is somehow preferable as a mode of communication.

Krassner: Exactly — with The Realist I would never label an article as either journalism or satire because I didn’t want to deprive the readers of the pleasure of discerning for themselves what was true and what was an extension of the truth.

Fish: I remember you saying that for years you received letters from people who thought that your famous piece about the Kennedy assassination was real investigative journalism.

Krassner: I still get them!

Fish: And that speaks to how absolutely bizarre reality can be in comparison to satire. The fact that you were able to write something that was so fantastic and so ludicrous and still have people confused about whether it was fiction or nonfiction, even 50 years later, is really telling about how the world works. It reminds me of an argument that I have with 9/11 conspiracy theorists all the time. I’m forever telling them to expand their rage and distrust of the government beyond what happened on September the 11th because if you’re looking for examples of how distrustful Washington is and how the president is a complete asshole [who is] able to commit unforgivable crimes against humanity and [who can] kill thousands of innocent people for purely political reasons, just look at his domestic policies against poor and underprivileged people living in the country right now. Look at his foreign policy, which is not secret and is published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal every day. For fuck’s sake, beginning with the sanctions against Iraq, implemented by the first Bush in ’91, straight through until now, we’re responsible for millions of deaths that could have been avoided. Then there’s Clinton’s bombing of the Sudanese pharmaceutical plant [in 1998] that destroyed the lives of millions of people. The point is, by sitting across the street from the White House in a windowless van with your night binoculars trained on shadows you see through the curtains you risk missing what is already happening in broad daylight, which is stuff that is way worse than what you’re trying to uncover.

Krassner: Right, like looking for dirt on Eva Braun.

Fish: [laughs] Exactly!

Krassner: But, yeah, getting back to your point about satire, it is much harder to create satire when the world, itself, is naturally satirical.

Fish: So then we have to ask the question of what jokes do. Do jokes spotlight what is already funny about the world or do jokes reinterpret the world and create something funny about it? Is it funny, for example, that lawyers are cheats and politicians are liars or is it unfunny that lawyers are cheats and politicians are liars and jokes help us deal with the misery of that reality? Does satire defang the monsters that we feel most threatened by or does satire give us sanctuary from those monsters the same way that being locked up in a prison cell protects us from the terror of having to keep up with a mortgage and maintain a lawn? Which came first, the chicken or the rubber chicken?

Krassner: I don’t know that there’s an answer to that.

Fish: Well, I do feel that satire has opened my eyes to certain things, but I’m not sure if it is my inner eye or my outer eye that was opened.Krassner: I remember when I was a counselor at a summer camp and how they would show Charlie Chaplin movies and some counselor would inevitably get up and say, “Now, the deep social message that Chaplin was trying to convey in the scene when he had to eat his shoelaces … ” — you know? We were all talking about why we laugh and the kids were saying, “I thought he had a funny walk.” So, again, there’s that innate sense of humor that we can all tap into and maybe that defangs the monster.

Fish: At least the monster that we project onto the world with our own pessimism. That was what John [Lennon] and Yoko [Ono] said when the press accused them of not taking the protests against the Vietnam War seriously enough. They said that they were willing to be the world’s clowns [during their Bed-In event], the idea being that humor is anti-violent. They made the point that you’re unlikely to attack somebody else, much less kill them, when you’re having a laugh.

Krassner: And yet satire is often called a weapon.

Fish: Which brings us back to the precariousness of jokes designed to do something more than just make people laugh. A satirist is either funny when you agree with him or downright mean when you don’t. In fact, there are a lot of people who won’t even call satire art precisely because it involves [political subject matter]. They’re the same people who insist that the surest way to fuck up a piece of art is to inject politics into it.

Krassner: There again, it’s all about the individual perception. Some people need politics injected for it to qualify as art.

Fish: I agree. There’s also a pretty good argument for how injecting art into politics can fuck up politics — at least how one relates to politics on a personal level. The example that I always give is how watching “The Daily Show” and “The Colbert Report” can fool a person into thinking that he or she is being politically active when he or she isn’t. It’s because watching TV is a private act and engaging in political activity is a public [act] and when somebody is at home watching a television show, though he or she might be agreeing with jokes about, say, the criminality of the president or the injustice or a piece of domestic or foreign policy, he or she is not doing anything about it. In that way, laughter can deter political activity.

Krassner: I know what you mean, sure. On the other hand, [my wife] Nancy memorized Mort Sahl’s first album [“The Future Lies Ahead,” 1958] when it came out and when you memorize something like that you really pick up on a lot of nuance about how the country works. You absorb a lot of critical thinking; it’s a very subtle process. And that can be politicizing and make you politically minded at the very least and make you behave a certain way. I remember when I lived in San Francisco and attending the annual Comedy Day in the Park. This was in the ’80s in Golden Gate Park and there was a long string of comedians and the only thing I remember from the day was a guy standing up and saying, “Isn’t Reagan an asshole?!” And the audience [went] crazy with applause and yells and the guy [said], “Oh, so you like the political stuff.” So there are different standards of what being politically minded means. Sometimes you can be political without naming names. Guys like Mark Twain and H.L. Mencken and Will Rogers were all political.

Fish: And so was Bruce, though not overtly so.

Krassner: Lenny Bruce died to make it safe for Jon Stewart to get laughs by saying words he knows will get bleeped out.

Fish: Further proof that Bruce didn’t die for our sins, but because of them. God, I miss that guy.

Krassner: Yeah, me too.

Fish: I guess what I worry about is the ability of a good political joke to defuse the rage that a person might have for a politician who deserves all the vitriol that we can throw at him. Sometimes I think it’s more important to embrace the discomfort that comes from being pissed off about something than to have your disdain obliterated by the relief you get from laughter.Krassner: Lenny and I used to talk about this stuff all the time and his position was that people don’t like to be lectured at. He believed that if you [could] make somebody laugh with a joke that [had] some truth about society embedded within it, the fact that they’re laughing indicates that their defenses are down and that they’re more likely to consider the information you’re telling them. The joke makes it impossible for a person to guard against [the wisdom of the argument] you’re presenting.

Fish: Plus, if it’s a good joke then it will bear repeating to more and more people and the information can become viral that way. It’s like a catchy tune that you want to hear again and again.

Krassner: Right — I’m relatively jaded and if something really stirs me, either a contradiction or an absurdity or a horrible cruelty that has been euphemized, and that will set my EEG off, then I’ll want to create a satire that crystalizes that contradiction or whatever it is and I’ll want to share it with people. Then, if it’s funny, those people will want to share it too. It’s how The Realist grew. Steve Allen was the first subscriber and he gave a bunch of subscriptions to a lot of other people, including Lenny Bruce, and then Lenny sent out a bunch and the magazine really took off that way.

Fish: Of course, when it comes to the catchiness of tunes that people want to hear again and again, taste can sometimes trump nutritional value. There’s the two-step, but there is also the goose step.

Krassner: Right. Now that you mention it, I think Malthusian was the word they used to use before viral.

Fish: Of course — yesterday’s torture is today’s enhanced interrogation.

Krassner: And dead babies [have always been] collateral damage.

Fish: And, thanks to people like you and Lenny Bruce, “fuck the government” will always mean “fuck the government.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.