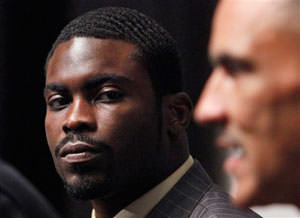

Michael Vick’s Long, Strange Detour

After doing prison time for dog fighting, he played Sunday in his first regular-season game in almost three years. But his re-emergence in the NFL has revived questions that arose when the scandal broke. And for one journalist, the issue was personal.His return as a fully reinstated NFL player has revived questions that arose when the dog-fighting scandal broke.

Early last month I experienced what I’ve been calling a mini-crisis of conscience. In most ways, it was a garden-variety upset, but in one way it was odd: The cause was a man I’d never met, someone I’d seen only in a few photographs and TV broadcasts. Until I started to research this article, my knowledge of him was confined to his activities in the two particular spheres that had thrust him into the national spotlight, and I didn’t know much about those either.

The person in question gained fame as a running quarterback who excited legions of National Football League followers. He was the league’s No. 1 draft pick in 2001 and over a handful of seasons with the Atlanta Falcons became a three-time choice for the Pro Bowl and the third-best quarterback in league history in career rushing yards.

In addition to being admired by perhaps millions, he earned millions: In 2004 he signed a 10-year contract for $130 million, and money from his endorsement deals was flowing in torrents.

Later, his fame was eclipsed by a dark notoriety. This once-celebrated athlete came to be widely scorned as “The Dog Killer” and, according to a poll published in July, he was the most disliked person in American sports.

Michael Dwayne Vick is the fellow who scrambled a cubic centimeter of gray matter somewhere deep within my brain. But I won’t get into my delicate little condition just yet. Hang in for a while and I’ll open that can of spaghetti. First, let’s look at Vick and how he got to be what he is today — a 29-year-old who in late August returned to the NFL preseason field after suffering one of the most dramatic downfalls in the history of U.S. sports, and who on Sunday played in his first regular-season game in almost three years.

Vick had a hardscrabble childhood in a public housing project in a bad part of the Virginia city of Newport News, known on the street as Bad Newz. Years later that bitter nickname would be associated with something much uglier than the seedy parts of a port town.

“As a grade schooler, Michael … showed tremendous promise in baseball and basketball,” one biography says. “By junior high, however, his adolescent angst got the best of him, and he became a disciplinary problem for his teachers. His mother pushed him to get involved with an after-school activity. Michael chose football. … ”

In high school Vick was a quarterback sensation, eventually winning a scholarship to Virginia Tech, where his star continued to shine. After his sophomore season at the university, the door of the Holy of Holies of American pop culture opened to him: He entered the NFL, where heroes are born and die, where legends shoot from raucous stadiums into the fantasies of boys staring into TV sets across the land.

Like most other football players, he had injuries (once he suffered a leg fracture) and periods of poor performance, and an Internet writer went so far as to contend at the end of the 2003 season that he “has done little or nothing to provide supporters with any evidence that he can, indeed, be the leader of an NFL football team.” However, one NFL Web analysis noted recently that his fans had been “intoxicated by his electrifying running skills and playmaking ability.”

For every one person who badmouthed him, there seemed to be many others who loved the man. That was before he got extremely bad press. And before he got extremely bad press he got some ordinary bad press, by flipping a double bird to fans in the Georgia Dome and being a difficult person in general. Also, his public image wasn’t helped any when he was hit with a lawsuit in 2005 by a woman who alleged she had contracted genital herpes from him. Eventually, the case was settled out of court under undisclosed terms.

In the happy days of big paychecks and cheering fans, Vick’s life appeared golden. But beneath the gleam lay a dirty secret that would throw out tentacles to yank this hero from his pedestal. In April of 2007 authorities raided a Virginia property owned by the quarterback and discovered 66 dogs and a dog-fighting pit. For Vick, the first domino had fallen.

In June of that year canine remains were found at the property, and in July, Michael Vick, presumably a role model to America’s youth, was indicted on federal charges. The name of his Virginia operation became known throughout the country: Bad Newz Kennels. Bad newz indeed.

Federal authorities alleged that he had been part of a dog-fighting ring that offered purses as high as $26,000. They also charged that Vick and other indicted men had “executed approximately 8 dogs that did not perform well in testing’ sessions” or fights. Some of these animals were hanged or drowned, the feds said, and at least one was killed by being slammed to the ground. It appeared that quite a bit of invention had been employed in finding ways to dispatch animals that did not measure up. One luckless canine competitor was electrocuted, prosecutors said. (Click here to see a copy of the indictment, which begins under a short news report.)

The allegations in the indictment — almost unimaginable to many who had followed Vick’s career — reverberated throughout the media. Rage echoed in the sports world and elsewhere, especially among pet lovers. Petitions demanding that Vick be barred from football sprang up. (In fairness it must be noted that there have been petitions in his favor, too.)

In July 2007, Vick pleaded not guilty and issued a statement that read, in part: “Today in court I pleaded innocent to the allegations made against me. I take these charges very seriously and I look forward to clearing my good name. I respectfully ask all of you to hold your judgment until all of the facts are shown.”

At one point in 2007 he told the NFL’s commissioner and the owner of the Atlanta Falcons that he was not personally involved in dog fighting, but later owner Arthur Blank would say that his quarterback had lied to him: “You think you know somebody for six years and you find out another side of their personality that you didn’t know. … It’s very sad.”

Vick’s own father indicated that his son had not been truthful in denying involvement in dog fighting. Michael Boddie (Vick uses his mother’s original surname) claimed that sometime around 2001 Vick kept dogs in the backyard and staged fights in the garage of the family’s Newport News home. Boddie went on to dismiss the suggestion that Vick’s friends were to blame for the Bad Newz Kennels’ dog-fighting operation. “I wish people would stop sugarcoating it,” Boddie said. “This is Mike’s thing. And he knows it.” (Brenda Vick Boddie, the quarterback’s mother, denied her estranged husband’s account.)

A key issue in the Vick scandal is gambling. Although he admitted he had bankrolled betting operations, Vick maintained in 2007 that he personally had never placed bets on dog fights, and ever since then he has held to that statement. Gambling. The word itself is enough to send shivers through most college and professional athletes. A disclosed tie to gambling has the power to end a sports career. It has the power to forever tarnish a reputation; just ask Pete Rose.

In late August 2007, Vick pleaded guilty to having participated in illegal dog fighting and was suspended indefinitely from professional football. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said in a letter to the disgraced player: “Your admitted conduct was not only illegal, but also cruel and reprehensible” [and regardless of whether you personally placed bets] “your actions in funding the betting and your association with illegal gambling both violate the terms of your NFL player contract and expose you to corrupting influences in derogation of one of the most fundamental responsibilities of an NFL player.”

The letter continued: “You have engaged in conduct detrimental to the welfare of the NFL and have violated the league’s personal conduct policy.”

That December, Vick was sentenced to up to 23 months in prison. The judge made his term longer than those of two co-defendants because the former Pro Bowl player had been “less than truthful” about his involvement in killing pit bulls. Although Vick declared that he had owned up to his felonies, the judge wasn’t buying it: “I’m not convinced you’ve fully accepted responsibility.” Quoting an NBC Sports Web site:

Flanked by two defense attorneys, Vick spoke softly as he acknowledged using “poor judgment” and added, “I’m willing to deal with the consequences and accept responsibility for my actions.”

Vick apologized to the court and his family members, who along with other supporters occupied most of two rows in the packed courtroom. …

“You need to apologize to the millions of young people who looked up to you,” [U.S. District Judge Henry E.] Hudson said sternly, reminding Vick of the fans he singled out when he pleaded guilty in August.

“Yes, sir,” Vick answered.

In July 2008, while he was in prison, Vick filed for bankruptcy protection. Although news reports at the time differed on his assets and debts, most of the accounts said he reported owing $10 million to $50 million to creditors and that his assets were in the same range.

Documents in the bankruptcy proceeding said Vick owed the Falcons $3.75 million, bonus money the Atlanta team was seeking to recover on the ground that he had broken his contract.

The football salary was gone, the endorsements had long since evaporated. Vick, whatever his remaining assets might be, was working for less than a dollar a day in the pen.

On June 12, 2009, the Atlanta Falcons — less than five years after signing the $130 million deal — released Vick from his contract. One effect of the action was to allow him to sign with any team … if the NFL would let him return.

After 18 months in prison and two months of house arrest in Virginia, Vick emerged, and in July Commissioner Goodell promptly reinstated him, conditionally. Goodell said he hoped to grant full reinstatement by the sixth week of the NFL regular season, at the latest. The league boss was quoted as saying:

“I have thought about every alternative. But I think this gives him the best chance for success. We are not looking for a failure here, we are looking to see a young man succeed. … I do recognize that some will never forgive him for what he did. I hope that the public will have a chance to understand his position, as I have.”

This is the point where Michael Vick started kicking me around, psychologically speaking.

I had read about the scandal in 2007 and had casually followed later developments, but it wasn’t until Vick finished his prison term and got Goodell’s provisional blessing that I gave him any serious thought.

Predictably, the public outcry against Vick (along with some support for the quarterback resuming his career) resurged after Goodell announced the conditional reinstatement. It was after reading about the resulting protest that I started ruminating about dog fighting. My chow-Doberman-shepherd mongrel would look up at me through soft, intelligent eyes and I would wonder how anyone could allow two creatures of this species to lacerate or even destroy one another as a mob cheered them on. Dog fighting. Blood sport. Damn — what a premeditated evil.

Vick’s crime seemed worlds apart from some saloon flare-up in which a pro athlete breaks the nose of a guy who disses him. Dog fighting had to be carefully financed, planned and executed. And among the things Vick and his buddies had executed with premeditation were dogs that hadn’t made the grade in the pit.

A rich, applauded professional athlete somehow had allowed himself to be pulled into an old, old “sport,” one that appears to go back to pre-history, perhaps 15,000 years, to soon after dogs became man’s best friend. Sometimes, man has not been the dog’s best friend: Since ancient times, organized dog fighting has been practiced in many parts of the world.

After they pushed into Britain in the year 43, the Romans, who had taken along dogs for use against the enemy on the battlefield, were impressed with the ferocity of the British war dogs. Later, fighting dogs imported from Britain would entertain Romans in the Colosseum by going up against other animals, including elephants.

Over the centuries, the British were enthusiastic practitioners of “the sport of Queens, British nobility and society’s elite.”

University of Virginia professor Edmund P. Russell tells us that Queen Elizabeth I “helped popularize dogfighting in 16th century England,” often holding matches for visiting dignitaries. “The Queen resembled her own subjects in her passion for blood sports; the most popular was ‘bull baiting,’ or having dogs attack bulls, which provided both entertainment for the masses and also helped tenderize the bulls’ flesh before they were slaughtered for food.” It wasn’t until 1835 that Parliament outlawed dog fighting.

In the New World, dog fighting found a foothold among American colonists. The practice was legal and was sanctioned and promoted by the colonies.

Dog fighting became deeply embedded in American culture after the Staffordshire bull terrier arrived in the United States from Britain in 1817. The United Kennel Club, America’s second-oldest all-breed registry of purebred dog pedigrees, endorsed the activity, made rules to govern it and sanctioned referees. Many policemen and firemen frequented the fighting pits, and at one time the periodical Police Gazette was a source of information on dog fighting. Finally, by the 1860s, civilization won out and dog fighting was declared illegal in most states.

In New York state, all forms of animal fighting were outlawed in 1867. One year later, authorities arrested Kit Burns, the proprietor of a notorious Manhattan establishment called the Sportsman’s Hall, which contained one of the city’s biggest dog-fighting pits and where gentlemen of the day could delight in dogs shredding each other or in death matches between terriers and rats.

An animal-protection site called AnimalLaw.info, affiliated with the University of Michigan College of Law, quotes a graphic description of a dog fight from a fictionalized account based on the real-life doings at the Sportsman’s Hall. The excerpt — which accurately reflects the accounts of actual dog fights that I have read — is from “The Hungry Eye,” an illustrated novel by Joshua Brown, a scholar of 19th century American life and a professor at City University of New York. Delicate readers are urged — seriously — to skip over this passage.

The dogs seemed to explode out of their restraints, two projectiles flying into the air toward the center of the pit. They met under the gas jets and, leaving a trail of spittle and hair, collapsed in an entangled, heaving heap onto the dirt. …

The dogs tumbled on their sides and Crib broke free. He dove back onto Butts, catching the back of the brindled dog’s head. Butts shook and jiggered, arched his back, tried to loosen Crib, the fine hair of his skull blushing gruesomely. Crib threw his head back, yanking Butts up. He whipped his head down. Butts hit the ground hard, his legs splaying like the splatter of an overturned pie. But Crib had lost his grip. Butts twisted his trunk around, swiveled onto his back, front paws revolving, back legs churning in the air. Crib leapt toward his exposed throat. The crowd bellowed, prepared for, anticipating, the blood. …

The dirt was turning to syrup around the dogs’ tethered heads. The bloody skulls thrashed in a terrible unison, Butts’s muzzle gaping helplessly up at the gaslights, Crib grinding downward. …

Now the crowd got what it came for. The blood cascaded down Crib’s breast. Butts worked his jaws, deepening and widening the wound, aided by Crib’s jerks and jumps. They lurched together across the pit to the atonal music of the surrounding chorus, Crib’s muzzle propped on Butts’s probing skull. …

Stamping, applauding, whistling, yelling, the men demanded their due. Winners or losers, they hungered now for a glorious, fatal finish — a magnificent kill was imminent!

I will not comment on that.

As of 2008, dog fighting was a felony in every state. In May of 2007, coincidentally at about the same time that the Vick affair was bursting into the national consciousness, a federal law against dog fighting was enacted. The Animal Fighting Prohibition Enforcement Act was designed to help Washington crack down on organized fighting involving dogs, roosters and other animals.

One sign of the ongoing prevalence of dog fighting in this country came last July 8, the date of the “largest simultaneous dog-fighting raid and rescue in United States history.” Federal, state and local authorities in six states — Missouri, Illinois, Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa and Mississippi — saved more than 400 dogs and made arrests.Subjects of high public interest generate magazines, and dog fighting is no exception. There are a number of publications that dance — rather clumsily — around the edges of illegal dog fighting. AnimalLaw.info names five magazines that it alleges are of interest to the dog-fighter community. One not mentioned is the now defunct Pit Bull Reporter, which continues to have a Web site. Internet visitors still can purchase “reprints of old pit bull fighting magazines from the 1950’s-1980’s” that “often contain graphic images of fightings [sic] dogs in the pit!” The site adds: “If that does not interest you or you find it offensive, please move on!”

The reprints — $12 each, $30 for three — are of “historical, educational, journalistic and artistic value. Not intended to violate any egregious, oppressive new law which arbitrarily, illegally and unconstitutionally infringes upon the 1st Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America. …”

The site is heavy with disclaimers: “ … If any person or agency is aware of any violation of any laws … by the information presented on this web site … we urge you to notify the editor/publisher for immediate resolution. Otherwise we will assume the 1st Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America is still in effect and this publication will exercise its right to freedom of the press and freedom of speech.

“God protect us against those enemies, foreign and DOMESTIC who would steal our Constitutional rights and our liberty! FREEDOM!”

Atop one article on PBReporter.com is a statement: “This information is … in no way intended to encourage or promote dog fighting or any illegal activity. In fact, it is our hope that with this knowledge the cruelty involved with some curious people ‘trying’ their non-pit dogs against an APBT [American pit bull terrier] may be averted and save their dog the physical harm and mental trauma which would result from such an experience. While we do not necessarily feel there is any cruelty involved in the ‘pitting’ of one APBT against another of similar size, as that breed enjoys the ‘exercise[,]’ very few individuals of any other breed would find it enjoyable or even tolerable for long and would quickly demonstrate their dismay with being involved in the situation. …”

Perhaps to appeal to potential subscribers less interested than the publisher in displaying the fruits of the First Amendment, the magazine was mailed out in “sealed white or manila 9”X12” envelope for your complete privacy! There is no mention of ‘pit bulls’ anywhere on the envelope.” Unmarked, sealed envelopes: animal porn arriving undercover at American homes, much like Playboy’s soft porn.

A Web site that promotes responsible dog ownership lists “techniques of neutralization” from a 1957 sociological study and applies five points from that study to dog fighters’ attempts to justify what they do. Here is that site’s list, paired with excerpted comments that a second site, Animal Law, published in dealing with the same study.

l. Denial of the victim, wherein the offender maintains that whoever is harmed by an action deserves the harm. “Most dogmen adamantly deny that the dogs are victimized by the culture of dogfighting. The dogs are glorified as fighting machines with insatiable blood-lust. … There is a perception that in the fighting circuit, the dogs get whatever they deserve.”

2. Denial of responsibility, wherein one contends acts are caused by forces beyond one’s control. “ … [O]ne archetypal ‘dogman’ found moral vindication through denial, ‘We’re not hurting anybody and the dogs love to fight, so what’s the harm? If you could see the way the animals love it … you wouldn’t think it was cruel.’ ”

3. Denial of injury, wherein one claims no one was harmed by the action; hence, there is no victim. “Many fighters claim that the dogs are treated well, both before and after the fights, and what happens in the pit — well, ‘they enjoy fighting.’ ”

4. Appeal to higher loyalties, wherein attachment to smaller groups takes precedence over attachment to society. “ ‘Old timers’ are lauded as warriors, heroes, and role models. … Many fighters maintain that dogfighting is a rich tradition with cultural and historical significance that is proudly passed from generation to generation.”

5. Condemnation of the condemners, wherein those who denounce a certain form of behavior have, themselves, exhibited worse forms of behavior. “Dogfighters often see themselves as a misunderstood group, victims of cultural genocide. … One website … has an entire section devoted to news of ‘abuses’ committed by humane workers, or ‘humaniacs’ as the dogmen often refer to them.”

I will leave it to you to make any connection between any of those techniques of justification and the sort of language seen in Pit Bull Reporter (which is far from alone is expressing such sentiments).

Dog fights, which usually occur in wooden enclosures, sometimes go on for hours, until one of the combatants cannot continue. Some animals die in the pits or later from cuts, broken bones, dehydration, exhaustion or shock. Infections — and the wrathful owners of losers — kill many wounded dogs after fights.

A Britannica.com blog had this to say about the owners and dog fighting.

A Chicago police officer who works to uncover and stop dogfighting attests: “They beat these animals. They feed them hot peppers. Feed them gunpowder. Lock them in small closets. They do everything they can to make these animals vicious and mean.” The dogs become powerfully strong and aggressive. Losing dogs often bear the brunt of owners’ and trainers’ anger at their loss of status and money: many dogs are found dumped with untreated severe injuries or are tortured or hanged after losing fights. And the dogs themselves are not the only animal victims: smaller animals such as kittens, puppies, and rabbits—often stolen pets—are killed and used as “bait” in training fights.

Some trainers use a “catmill/jenny,” a conditioning device in which several arms stick out from a rotating pole in the center. Dogs are chained to one arm and a small animal is attached to another. The dogs run in circles in an effort to grab the bait, which at the session’s end usually is given to the pursuers to tear apart.

Another charming tool of the trade is the springpole or jumppole, which features a spring on which a hanging object such as an animal hide is attached. A dog being trained will bite into the object and hang there for long periods, strengthening the jaw and other parts of the body. For the spice of variation the trainers may replace the hanging object with a cage containing a bait animal; this causes the dog to leap over and over in trying to seize the terrified bait.

The problem of professional dog fighting in rural areas, such as the locale of Bad Newz Kennels, is compounded by a more casual form of the brutality in cities — so-called street fighting — which is outlined by the ASPCA:

“Street” fighters engage in dog fights that are informal, street corner, back alley and playground activities. Stripped of the rules and formality of the traditional pit fight, these are spontaneous events triggered by insults, turf invasions or the simple taunt, “My dog can kill yours.” …

“Street” fights are often associated with gang activities. The fights may be conducted with money, drugs or bragging rights as the primary payoff. … “Professional” fighters and “hobbyists” decry the techniques and results of these newcomers to the blood “sport.”

Just as music is an element of movie and TV dramas, the subject of music often appears within the Michael Vick saga. Hip-hop is linked to dog fighting in the eyes of some animal-protection advocates, and a number of Web sites mention the Vick case in discussing dog fighting and hip-hop. One of the favorite targets is rapper DMX, who has written lines such as “Place your bets/ You can imagine what the bloodline is like” and “All my pups is crazy, ’cause off the leash/ They can eat, stand a match for three hours at least.” The cover of DMX’s album “Year of the Dog Again” shows the rapper with a pit bull that is snarling grandly.

However, hip-hop does not go undefended. A 2007 MTV.com article minimizes the role of dog fighting in hip-hop culture under the title “Why Does the Michael Vick Case Hurt Hip-Hop?: Genre’s glamorization of dogfights and pit bulls has led critics to associate it with blood sport.” It notes that critics of dog fighting have attacked the “scene in [rapper] Jay-Z’s ‘99 Problems’ video where everyone is getting ready for a big dogfight …, DMX’s album Grand Champ (which is the title given to a dog that wins five matches without a loss), and DVDs of dogfights sold alongside mixtapes in some parts of the country.”Another member of the camp that finds exaggeration in the grouping of hip-hop and urban black America with dog fighting is the commentator Earl Ofari Hutchinson, who complains that the Vick headlines have fueled false claims that dog fighting is rampant “in poor, black urban neighborhoods.” He mentions the criticism of Jay-Z and DMX and concludes that wrongly magnified allegations about inner-city blacks make “good copy and unchallenged public belief … [and are] the stuff of a brand spanking new urban legend.”

All this information about dog fighting contains a savagery and bloodlust that will put off some readers, but the dirty job was necessary to paint a full picture of what Michael Vick had been up to, and why so many animal lovers were up in arms about his returning to the NFL.

In the forefront of the campaign against Vick is People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Now, as you may know, PETA has not always been a perfect model of moderation. During an interview with CNBC in June, President Barack Obama swatted a fly, with fatal consequences for the insect, and that did not sit well with PETA. The organization denounced the action of the quick-handed president as an “execution” and sent him an insect trap-and-release device. Plainly, PETA will not compromise its positions regardless of who is in its cross hairs, and often it comes across as — what is the most diplomatic word I might use? — fringe-y. But that doesn’t necessarily mean those positions are wrong.

Some of PETA’s spokespersons were breathing fire in late July as they pressed their case against Vick. One PETA representative, appearing on MSNBC’s “The Ed Show,” declared that Vick must not be allowed to play NFL football until he was genuinely remorseful. And how could that be determined? Through a neurological exam and a brain scan. A brain scan? I was watching the original broadcast of the program and was amazed by what I had heard. Was there now a scientific way to peer into the human soul?

So, off to the computer I went. I typed PETA and brain scan and Michael Vick into a Google search prompt, and, sure enough, there it was, PETA saying: “The only way to know for sure if Vick can change his ways is for him to submit himself for a brain scan and psychological test. Based on a number of factors—such as the fact that the right side of the hippocampus is larger than the left in 94 percent of captured psychopaths—these tests can help determine if Vick can ever truly understand that dog fighting is a sick, cruel business. Or, they could suggest that he’s doomed to repeat mean, violent behavior in the future—whether with dogs or other human beings. And given that Vick plans to be around a lot of kids, to give talks to them, and to be a star in their eyes again, the world deserves to know who he is inside.”

Why aren’t prison and parole authorities using this? I wondered. Well, it turns out that a researcher at a New Mexico prison is. According to an online article from a Stanford institute: “Researchers such as Kent Kiehl are currently making strides in locating neurological markers of psychopathy. … ” Wonderful, eh? But the sentence continues, “but they are not yet able to reliably use brain scans to diagnose someone with ASPD [anti-social personality disorder] or psychopathy.” (To read everything you conceivably could want to know about Dr. Kiehl and his research, check out a separate, long article in The New Yorker.)

If the article quoted above is right about the current ineffectiveness of the alleged “remorse detector,” and I believe it is, PETA is way, way premature in calling for a brain scan to determine whether Michael Vick is truly sorry for his crimes; the good doctor has an interesting hypothesis and little more.

Nevertheless, after taking several doses of PETA propaganda from print and television in July, I was getting religion. I was thinking that maybe, just maybe, the organization’s take on Vick shouldn’t be breezily dismissed.

I phoned a friend and we started talking about the controversy. I made some remarks about Vick that were mildly profane and utterly uncharitable. My friend replied, “Isn’t that a little harsh? Don’t you think an ex-convict should be allowed to make a living at his profession as long as it’s legal?”

“He looks like a monster to me,” I replied in giving a non-answer.

“Even monsters can reform,” my friend said.

Drawing on my formidable debating skills, I countered, “Oh, go screw yourself.” We laughed and the conversation moved on to other areas.

For the next several hours I didn’t think about the man who seemed to be working his way ever higher on my personal “most-disliked” list.

That evening, after watching a television recording I had made, I got up from my sofa to brew a cup of tea. En route to the kitchen I noticed that my heartbeat was up a bit from the excitement of the action I had seen. Mixed martial arts. It had been a hard-fought match that seesawed back and forth before one of the competitors knocked his opponent down with a combination of punches and kicks. He then straddled the fallen man and pummeled him until the referee hurled himself over the defeated combatant. The winner exalted himself, raising his arms in victory as he ran around inside the cage taking in the adulation of the cheering crowd.

By that time, the loser had risen and his face was awash with blood, which had speckled the canvas near where he had been decked. A physician was checking him, and the fighter’s seconds looked on with concerned expressions on their faces.

As I removed a cup from a cabinet, I was thinking: Good match. But damned bloody business. A doggone bloody sport. And that was when I had a thought that almost made me drop my cup: blood sport.

Had I — in the comfort of my living room — been part of a mob witnessing a blood sport? Well, not if you define blood sport as killing something: Everyone in the cage appeared to have survived. But there was no shortage of blood, nor had there been any lack of organized, premeditated violence amid a rabble cheering for still more. And, at least in boxing, in rare cases a corpse has been hauled out of the ring. In principle, had I engaged in a minor-league version of what Michael Vick had been sent to prison for doing?

Though I had not struck any blows, clearly I had endorsed the rearranging of someone’s facial features without benefit of surgery. I had endorsed this violence with my presence in front of the TV set — with my eyeballs, by watching two members of my own species spend almost 15 minutes trying to hurt and incapacitate each other.

I also thought of the many boxing matches I had witnessed and, sometimes, even had paid to see. I once saw a videotape of a fight in which a boxer was fatally injured. And not long ago I watched a rebroadcast of a match in which one of the boxers was carried away to a hospital and ended up paralyzed and in a coma, before he faded from public view and attention, as wounded prizefighters almost always do. Is he dead? I’d never heard, nor was I able to find out.

I thought of the bullfight I had paid to see in a foreign country. It wasn’t much of a fight. Kind of one-sided: First, the enraged and outmanned animal was stabbed by a lance wielded by a horseman, and then sticks with a cruel barb on the business end were thrust into its hide and muscle. All of this was done by an enthusiastic crew trying to get the beast in the right state of mind to have a sword plunged deeply between its shoulder blades. I saw none of the glory that Hemingway writes about in “Death in the Afternoon.” But I did see death that afternoon, and plenty of blood soaking into the sand of the arena. The performance was light on plot — humans torment animal, animal tries to gore humans — but it was warmly received by the audience, of which I was a member.

I thought, too, of the duck I had inspected after I shot it from the sky. I recall being awed by its beauty even in death: The greens and blues of its sleek feathers seemed to give off an iridescent light. I had paid a considerable number of good American dollars to put myself in a position to render this creature lifeless. As I looked at the dead fowl, it seemed I had committed a moral crime in killing it merely for the pleasure of doing so — with no intention of eating the kill — and it seems a moral crime now, many years later.Was the pleasure I had, or hoped to have, from the martial arts fighting, the boxing, the bullfight, the duck hunt, that much different from what was experienced by Michael Vick and his guests at the Bad Newz Kennels festivities? Though there was a legal difference, and a difference in degree, was there a difference in principle? The question was perplexing, and it rested heavily on me.

Remember those five points of “neutralization,” or justification, from the 1957 sociological study? Let me try them on for size in regard to boxing, and attach some thoughts I’ve had at one time or another over the years.

l. Denial of the victim, wherein the offender maintains that whoever is harmed by an action deserves the harm. “Yeah, some fighters get hurt pretty badly, even killed, but they know what they’re getting into.”

2. Denial of responsibility, wherein one contends acts are caused by forces beyond one’s control. “It’s not my fault if a fighter gets crippled. You can’t keep boxers out of the ring. And if you just could see the way they love it, you wouldn’t think it was cruel.”

3. Denial of injury, wherein one claims no one was harmed by the action; hence, there is no victim. “Only rarely does someone get really hurt. They’re tough guys and they can shake it off.”

4. Appeal to higher loyalties, wherein attachment to smaller groups takes precedence over attachment to society. “The Sweet Science: Jack Johnson and Dempsey and Louis and Marciano and Ali. It’s a grand American tradition cherished by many thousands. Ernest Hemingway and Norman Mailer boxed. Joyce Carol Oates is fascinated with boxing, and so are lots of other smart people.”

5. Condemnation of the condemners, wherein those who denounce a certain form of behavior have, themselves, exhibited worse forms of behavior. “Oh, that anti-boxing crowd will tear down any sport that’s rougher than lawn bowling. Those holier-than-thou hypocrites are always looking for something to criticize.”

Wow. Did that little list so easily couple with my own justifications? Yes, I’m afraid so.

A few interesting facts or assertions that I turned up about boxing:

— Ninety percent of boxers sustain brain injuries, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

— “The causal relationship between thousands of blows to the brain and diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s is accepted by most doctors involved in sports medicine.” (Can any sensitive person not be saddened by the present medical condition of Muhammad Ali?)

— “The British Medical Association, American Medical Association and Australian Medical Association all have standing policies that call for the complete banning of the sport.”

— Over generations, 1,465 boxers have died as a result of boxing injuries (as of November 2007).

Noteworthy information.

And noteworthy information of a different sort was on the cover of the Aug. 14 sports section of The Los Angeles Times. The headline read, “Vick gets next chance with Eagles.”

The article reported that “controversial quarterback” Michael Vick had signed a two-year deal with Philadelphia’s NFL team. Another article, from ESPN, gave figures provided by an unnamed source: “The first year of the deal is for $1.6 million with the second-year option worth $5.2 million. … Vick can also earn an additional $3 million in incentives over the two years of the contract. … ”

According to the L.A. Times, “Wayne Pacelle, president and chief executive of the Humane Society of the United States, said he doesn’t expect widespread protests and sees it as a good thing that Vick wound up in Philadelphia.

“It’s a city we’ve been looking at very closely because it has a major dogfighting problem. … So Vick’s landing there has the potential to turn around the issue. This gives us a big boost.”

So, where does this leave me and my mini-crisis of conscience? Will I never watch another boxing or MMA match? When the sinner knoweth his sin, doth he repent? As I now sporadically fiddle with the issue, I’m reminded of the famous prayer of St. Augustine: “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” Grant me a life free of vicarious brutality, but not yet. The matter has mostly subsided into the background noise of daily life, but still it buzzes ever so faintly at the edge of my awareness. At the very least, the bogus high ground that I stood on has departed in a landslide and I have a better view of the illogical and perhaps immoral contradictions within me.

As for Vick, has he cultivated the remorse that PETA has demanded? If we are to believe his words at an Eagles news conference Aug. 14, he is on the right road. Here’s part of what he had to say:

… I have done some terrible things, I made a horrible mistake. And now, I want to be part of the solution and not the problem. I am making conscious efforts within the community, working with the Humane Society, hopefully I can do that locally and continue with my disciplined efforts in bringing awareness to animal cruelty and dog fighting in the inner cities and our communities. …

I think everybody deserves a second chance. … I think as long as you are willing to come back and do it the right way and do the right things and that you’re committed, then I think you deserve it. But, you only get one shot at a second chance, and I am conscious of that. …

I was wrong for what I did. Everything that happened at that point and time in my life was wrong and unnecessary. And, to the life of me to this day I can’t understand why I was involved in such a pointless activity and why I risked so much at the pinnacle of my career. …

There was a point in my life when before I was convicted or before the allegations even came out when I knew it was wrong and I felt that it was wrong. Just when I was trying to turn the corner and it was too late, but everything happens for a reason and there is a reason I was sent to Kansas [prison] and a reason I was convicted. I was conscious of the fact that it was wrong and to this day I have to deal with that shame and that embarrassment.

Those words seem sincere. My doubts and critical thoughts about Vick have not totally evaporated, but with a droplet of charity seeping into my stony heart, I wish him well. I hope he avoids trouble and plays for 10 more years and redeems himself in the eyes of man and the gods of man and beast. The Humane Society of the United States has posted a video on its YouTube channel featuring Vick and others denouncing cruelty to animals. In the clip Vick says, “If you own a pet you need to love him with all your heart.”

As it turned out, there were no visible protests from fans in Philadelphia when Vick took the field Aug. 27 in his first preseason game after his return. When he left the game after only six plays, shouts of “We want Vick!” rang from the stands. Maybe we Americans do have the short memories that some of our international critics attribute to us. Or, to put a happier spin on it, maybe we just possess a bigger store of charity than they usually see in us.

But not everyone is as forgiving as those Eagles fans. A Philadelphia-area volunteer organization named Main Line Animal Rescue placed an ad in The Washington Post this month saying it would donate five bags of dog food to a District of Columbia animal shelter for each time Vick was tackled when the Eagles played the Washington Redskins on Oct. 26.

“There’s really nothing we can do about Michael Vick being in Philadelphia,” Bill Smith, founder of the shelter, said in a media report. “But I thought this would be a good way to come up with a solution where we could help a few dogs.”

Smith said his group planned to run similar ads in the hometowns of other Eagles opponents during the season. Next to a picture of a puppyish pit bull is the ad’s tagline: “Because there are no second chances on an empty stomach.”

When NFL Commissioner Goodell announced in early September that Vick would be fully reinstated as of the Sept. 27 game, the Eagles’ third of the regular season, it appeared that the athlete’s long, strange detour had finally ended. On Sunday, according to The Associated Press, “Some in the crowd rose to give Vick a standing ovation as he took the field [in Philadelphia]. … Before the game, a group of about 25 protesters gathered at the northeast entrance to the stadium, holding signs saying, ‘Vick is sick’ and ‘Ethics over athletics.’ “

Now it’s a game of wait-and-see.

Can the NFL, Goodell, the Eagles, football fans, pet lovers or anyone else be certain that Vick will not in some way fall from grace again? Of course not. Certainty is hard to come by in a world of humans pushed one way and then the other by fickle currents.

But one thing that is certain: I won’t be casting any more stones at Michael Vick. After a few weeks of thinking about my brother under the skin, and myself, I’ve concluded that I live in a glass house.

T.L. Caswell was on the Los Angeles Times editing staff for more than 20 years and now edits and writes for Truthdig.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.