Megan Hustad on Class in America

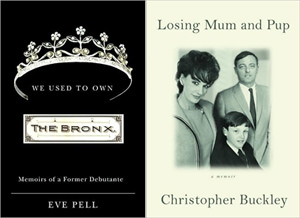

Two memoirs -- Eve Pell’s “We Used to Own the Bronx” and Christopher Buckley’s “Losing Mum and Pup” -- demonstrate, each in its own way, that all that glitters is not gold and that the price exacted by extreme social anxiety is very high indeed. A feast of the higher gossip and raw meat for social anthropologists.

“There is no such thing as society,” Margaret Thatcher announced in 1987. “There are individual men and women, and there are families.” So don’t blame your troubles on a competitive capitalist culture, she told the readers of Women’s Own magazine, and don’t feel entitled to government intervention. When it came to forging one’s way in the world, we were all mere products of our families—with no greater social forces to credit or fault for our successes or lack thereof.

Such “pro-family” pronouncements have left a stain on the literary memoir’s reputation. “Memoirs are a Thatcherite genre,” I heard a hung-over Marxist remark during a recent panel discussion at the New York Public Library. He explained that since memoirs, more often than not, treated individual family psychology as the critical factor determining the contours of a life, they were inherently conservative regardless of any political opinions espoused on the page. For a frank discussion about the influence of class on American life, you’d have to look elsewhere.

Losing Mum and Pup

By Christopher Buckley

Twelve, 272 pages

We Used to Own the Bronx

By Eve Pell

Excelsior Editions, 225 pages

Eve Pell’s “We Used to Own the Bronx: Memoirs of a Former Debutante” tests this proposition in a refreshingly direct fashion. A former senior staff reporter at the Center for Investigative Reporting now in her 70s, Pell can claim membership in the ranks of American nobility, and she uses her lively memoir of growing up in aristocratic style to ask a series of provocative questions: Is it possible to choke on a silver spoon? What good is a sense of entitlement? Are riches wasted on the rich? Her candid account of bristling at her birthright transcends the stereotype suggested by the subtitle to divulge the psychic pressures of living with inherited privilege in a meritocracy-mad country.

The Pell family had money, a lot of money. “In 1654, my forefather Thomas Pell, surgeon and fur trader, bought a large tract of wilderness from a council of Native American sachems.” From then on, their collective CV reads like a history textbook sidebar. They once owned Fort Ticonderoga. Pell Street, in what is now Manhattan’s Chinatown, is named for them. And thanks to a contract drafted in 1688, the city of New Rochelle, N.Y., is still obligated “if demanded” to present the Pell family with one “fatt” calf every June 24th.

Entering this august lineage right when the funds started to run low presented Pell with some interesting dilemmas. The Pell family—which now branched out to incorporate names like the Harrimans, Stuyvesants, Mortimers and Roosevelts—had an allergy to working for money. They fancied themselves aristocrats, and though this amnesiac fantasy is fairly common among rich Americans of their vintage, the Pells indulged a particularly virulent strain. (As Pell recalls, the Mellons could not possibly be envied—despite their deeper pockets—because they had made their fortune “in trade.”) Horatio Alger, Pell writes, would not have been welcome at their table:

“We took for granted a system antithetical to the American dream: instead of sons outdoing their fathers through better education and diligent endeavor, fathers lived better than their children. Instead of ascending steadily into wealth and status, families like ours gently declined. Once-huge fortunes were divided among offspring who had progressively less money, fewer servants, smaller houses, and by the time my generation came along, not even their own trust funds—we had to depend on our parents for handouts.”

Pell’s father, Clarence Cecil Pell II, humbles himself and takes a job in Manhattan, transferring mid-commute from the club car to a waiting limousine. Clarry was a cautious conformist in his daughter’s eyes; a snob by inclination and training whose intellect lacked the suppleness required to examine the fault lines in his worldview. “According to the Declaration of Independence, all men are created equal,” Pell writes. “But you’d never have sold that to my mother or my father.” They were of a caste that believed itself set apart from and above the masses. In a country increasingly in thrall to achievement, believing yourself superior when you have few noteworthy accomplishments to your name is surely difficult. (Never mind that your cash flow is also slowing to a trickle.) As Pell tells it, knee-jerk elitism and emotional constipation have their uses—both allow someone with a thwarted sense of entitlement to keep his or her chin up.

Pell’s mother—nee Evie Mortimer—does not come across as a woman blessed with self-awareness, but she did have wits enough to realize that a man who played his patrician role with flair was more to her liking. A few short years after marrying Clarry, Evie leaves him for Lewie Ledyard, a 6-foot-3 former classmate of her husband’s with a yen for horse breeding and cockfighting, and a faltering marriage of his own. Protracted divorces and custody battles marked Pell’s childhood; Clarry eventually relinquished custody of Eve and younger brother Cooky under the condition that the Ledyards assume all child-rearing expenses.

Pell finds out decades later that her half brother Peter regarded her and Cooky with great skepticism, having never been informed that he and these occasional weekend visitors shared a dad. (“A governess finally clued him in.”)

Given the affective deprivation tank that was her childhood, it isn’t surprising that Pell’s knack for detail is best displayed when she holds the physical trappings of upper-class life to the light. Her mother’s dark curls against a white chaise lounge, an embattled hemline on a boarding school uniform, china cups rattling in a nervous maid’s hand—the material world Pell conjures up glistens. She attends Byrn Mawr College and starts to wonder whether the culture of high-priced ennui is for her. “Only our failures marry” was the unofficial Bryn Mawr motto, but Pell—having been raised to think that words like failure simply didn’t apply to her set—is undaunted and she marries a young architect and heads west to San Francisco. Sacramento native Joan Didion once confessed that she didn’t really understand “The Great Gatsby” until she moved East; for Pell, the West beckoned as a place of myth and redemption where the demands of family and caste might dissipate.

The last part of the book offers a glancing overview of Pell’s immersion in early ’70s radical chic. She starts working with assorted anti-capitalists, joins the Prison Law Project and shares a brief kiss with Black Panther Field Marshal George Jackson in the visiting room at San Quentin. This account of Pell’s radicalism is made more compelling in that it didn’t require a fundamental shift of perspective—her world was not reimagined so much as flipped around. Pell at the revolution retained the strident elitism she was born to, only now black, brown and other oppressed peoples occupied the moral superior slots.

Losing Mum and Pup

By Christopher Buckley

Twelve, 272 pages

We Used to Own the Bronx

By Eve Pell

Excelsior Editions, 225 pages

Pell eventually realizes that she’s in over her head when a brick thrown through her window lands on her son’s bed. Satisfaction would have to be found elsewhere, and likely after dispensing with self-righteousness and resentment. To her lasting credit, “We Used to Own the Bronx” is a graceful object lesson in how perspective is gained not all at once but by accretion, the reward of years of methodical observation.

In a wistful prologue, Pell admits to lingering mixed feelings about her background. “My relatives include bigots, humanitarians, eccentrics, athletes, and ordinary people, most of them infused with a strong sense that they are aristocrats. Like them, I love it that our family used to own a manor in colonial America.” But “while the family forms a sort of bulwark against time, a base of permanence in a world of flux, it exacts a terrible price.” Her father, perhaps cruelly keen to put a fine point on his disapproval of her antics, disinherits her.

From the evidence assembled in his memoir “Losing Mum and Pup,” Christopher Buckley is entirely more sanguine about love among the ruling class. As the only son of William F. Buckley and Patricia Taylor Buckley, Christopher grew up having to fight for oxygen with two outsized personalities. William F., a rapaciously productive writer and founding member of the modern conservative movement, was demanding and competitive. When Buckley sent Dad a copy of his latest novel, he received his thanks in a curt e-mail P.S. (“This one didn’t work for me. Sorry.”) His mother, Pat Buckley, was a “beautiful, theatrical, bright as a diamond” hostess who towered over rivals in New York society with her near 6-foot frame and cutting wit. “I’ve got the best legs in the business,” she’d chirp, all the better to preside over the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual Costume Ball with. “She could have done anything; instead, she devoted herself heart, soul, and body to being Mrs. William F. Buckley.”

“Losing Mum and Pup” does not dwell on childhood. It zeroes in on Buckley’s parents’ last few months, respectively—they died within a year of each other—and how he held their hand as they left this “vale of tears,” to use one of Buckley pere’s preferred formulations.

Buckley did not set out to write a book about class or society, lower- or uppercase S. Yet if one were to take a red pen to all references to his family’s lifestyle—the homes, the boats, the winters in Switzerland—the end result would be far slimmer. “Is it namedropping when they’re your own parents?” he jokes in a self-conscious aside. To point this out is neither to fault Buckley’s skill nor his character; the story doesn’t work without the money.

But it also begs this question: If Pat occupied a different stratum of society, if you removed her from the Costume Ball and scratched her name off Mr. Blackwell’s best-dressed list, would she have been just another mean drunk? Buckley doesn’t detail many accounts of Pat’s alcohol-fueled spasms of unremitting obnoxiousness—if you’re looking for a Portrait of the Mother as a Real Bitch, stick to Pell’s story—but he is unambiguous about their frequency. He took to taking Pat to task in letters, letters that he later discovered she’d stopped opening. (One reads this and thinks he yelled via letter? As keeping up appearances goes, we’re approaching self-parody—or expert mimicry of Evelyn Waugh.)

Pat couldn’t stop herself from lying—a trait Buckley discovered when, age 8, he overheard his mother tell someone that when she was a child, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth would bunk at her family’s house whenever they breezed into Vancouver. As amusing as this anecdote is, indeed we’re told that Pat’s childhood home stretched to an entire city block. Royalty might not have supped there, but they could have; this subtext in Buckley’s book is rarely sub.

Before he spends the second half of the book discussing his father’s final months, Buckley pauses to grumble about the bill for his mother’s memorial service: $20,000 for audio-visual equipment alone. Never mind flowers, catering, or the bore of having to remind Henry Kissinger to keep his eulogy under four minutes. This grousing is expertly relayed and entirely disingenuous. Buckley’s delight in his family’s social position is palpable. The service was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Temple of Dendur—as Buckley terms it, channeling his inner 12-year-old, “roughly speaking the coolest place on the planet.” With this wry deprecation that does not truly deprecate, Buckley shows he’s more than adept at the upper-class sob story—an art form of supreme archness that boasts without appearing to condescend. No poor little rich kid narratives have so far made it into the American literary canon (it’s safe to assume, I think, that relatively few of us have enjoyed Consuelo Vanderbilt’s “The Glitter and the Gold”). Buckley’s contribution demonstrates, in part, why; only a skilled stylist can get the tone right.

Losing Mum and Pup

By Christopher Buckley

Twelve, 272 pages

We Used to Own the Bronx

By Eve Pell

Excelsior Editions, 225 pages

The second half of the book is genuinely moving. Buckley takes unalloyed pleasure in his father’s professional accomplishments, his energy and drive. Buckley has faced criticism for spilling intimacies which his parents might have preferred kept private, but “Christo” has done right by them in this respect: “Losing Mum and Pup” asserts that even when they acted badly, it was more finely articulated bad behavior than that indulged in by lesser mortals.

Asserting that only a grand [read: monied] scale is sufficient to contain its subject’s ambitions and appetites is, of course, what every memoir that originates in the American upper classes does. It’s as if being rich isn’t enough—one must, as Buckley says of his mother’s habit of mendaciousness, be “really, really good at it.” In a talk about the book at the 92nd Street Y, Buckley jokingly referred to himself as the “Frank McCourt of Park Avenue” before suggesting that no one should feel too sorry for him, and indeed, after the fifth mention of Henry Kissinger, one doesn’t.

That Buckley found sufficient consolation in his family’s elite status while Pell could not tells us something about their individual personalities and something about their families. It also tells us how inadequate Thatcher’s conception of human agency is; families don’t operate in a socioeconomic vacuum. Health and wealth can absorb hurt, mistakes, gross errors in judgment, even render chronic alcoholism relatively consequence-free. There are exceptions, of course—and again, Pell’s book offers the clearer picture of the price exacted by extreme status anxiety.

“My grandfathers were the best of the best in their league of the well-born,” Pell writes, tongue-half-in-cheek. One closes both memoirs with the creeping sensation that such feudal fictions were handed down because they proved absolutely necessary. Without that layer of brash self-assurance, those boarding school uniforms didn’t wear so well.

Megan Hustad, the author of “How to Be Useful,” is writing a book about class in America.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.