Mark Dowie on I.F. Stone

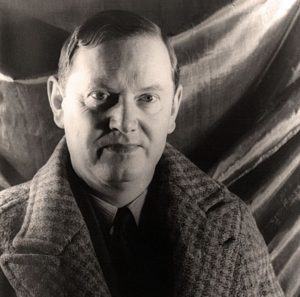

Critic and crusader, the late I.F. Stone was an American original. Neither changing times nor his failing eyesight blunted his radical edge or dimmed his acerbic wit. A new biography by D.D. Guttenplan gives us the man behind the legendary muckraker.

Every writer, of whatever genre, recalls one or two momentous encounters with a professional hero or mentor that either shaped their career, or gave them courage to continue. My most memorable such experience occurred in 1986 in Amsterdam, where a small group of leftish European and North American journalists gathered for dinner after a conference. As the evening unwound, I.F. Stone, known to almost everyone as “Izzy,” whose eyesight was failing, asked if I would walk him back to his hotel. How could I decline that request?

Through the narrow streets and over the canals of Amsterdam we walked in silence, Izzy no doubt pondering Socrates, whose biography he was completing; I, more nervous than a kid on his first date, trying to think of a conversation starter.

American Radical: The Life and Times of I. F. Stone

By D. D. Guttenplan

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 592 pages

The week before I had left for Europe, a right-wing database called Western Goals had made a file on me available to its corporate clients. A detective friend, able to hack into just about any data anywhere, found and gave me the file. Among other things, it described me as a “radical.” I was upset about that, fearing that such a characterization might limit, even ruin, my budding career.

“That’s a badge of honor,” Izzy growled. “You should wear it with pride.” What followed was a short dissertation on Edmund Burke, a conservative philosopher who, among other memorable things, said that “for every thousand people examining the branches of the tree of evil, you’ll find one examining the roots.”

“That’s radical,” said Izzy. “The Latin for root is radix … same derivative as radical. That’s what we do, isn’t it? We examine the roots of things … so we’re radicals. Let them call you what you are, and get on with your work.”

I have since that moment been comfortable calling myself a radical. So imagine my delight, as a fading investigative reporter, upon being asked to review a book about I.F. Stone, who, despite a controversial life and career, was clearly one of the most influential investigative reporters of our time … a book entitled “American Radical.” I will do my best to be objective, although I can already hear Izzy advising me to eschew the charade of objectivity, a worthy idea that in a world of war, injustice and mendacious government, is simply impossible to attain.

D.D. Guttenplan’s vivid and introspective biography contains far more delightful vignettes and unexpected intersections with true left luminaries and other global celebrities of the era. “American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone” recounts, in amusing detail, the long and productive life of a shy but clearly brilliant Jewish boy from rural New Jersey who began his writing career as a cub reporter, worked harder than most of his peers, penned heated polemics under various pseudonyms and eventually changed his total identity to I.F. Stone, the name under which, for two critical postwar decades, he wrote and published his legendary I.F. Stone’s Weekly newsletter, which became a teething ring for a whole generation of aspiring left-wing journalists, myself among them.

The book arrives at an appropriate moment in history as the current and apostate left reheat their debate over the worthiness, skills, accomplishments and patriotism of this complex, still mysterious figure in American media. Was Izzy Stone a journalist, or a propagandist? Was he a communist or an anti-Menshevik socialist, a spy, or merely a curious reporter willing to talk to anyone who could offer some insight into Soviet policy and the world of espionage? And who paid for those lunches?

Born in Philadelphia in 1907 (same year as my father) to working-class Russian immigrants, a shy and diminutive Isidor fell head over heels in love with the written word, dropped out of the University of Pennsylvania, declared himself a reporter and began working for small-town, blue-collar New Jersey newspapers, eventually making his way to Philadelphia, then to the New York Post, at the time a champion of New Deal liberalism, then to The Nation, a staunchly pro-Soviet journal of opinion, and finally to the nation’s capital, where, under the mantra “all governments lie,” he set about to expose the chronic mendacity of Washington. Along the way he met and married Esther Roisman and had three children. Esther became his assistant on The Weekly. As he went about the work of expository journalism, he seasoned, and as so many aging journalists do, began to ponder the historical significance of his work and the origins of his deepest beliefs. He ended his career as an amateur classicist, writing “The Trial of Socrates,” a poignant rumination on the fate of a heretic. Guttenplan’s 500-page biography is thorough to a fault, covering not only the endless stream of controversies that surrounded Stone’s own life and work, but also the intertwined social and political confusions that rocked an America The Weekly tried to make sense of. The book grapples with every issue that confronted serious journalists of the time — civil rights, federalism, McCarthyism, wars in Korea and Vietnam, sexual freedom and the American left’s gradual transformation from stodgy, pro-Soviet communism through democratic socialism to a vibrant new left libertarianism to which neither Stone nor his generation of leftists really never took. Any biographer would be remiss if he didn’t weigh in heavily on the question of Stone’s loyalty to his country and his alleged role as a Soviet spy. And Guttenplan does so, at some length, in drab detail.

American Radical: The Life and Times of I. F. Stone

By D. D. Guttenplan

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 592 pages

I suppose it’s harder for my generation to get too worked up over that tiresome parlor game, although it is still played ad nauseam by some of my contemporaries, notably Paul Berman and Ron Radosh. And most of us are less likely than Izzy’s contemporaries to care whether Sacco, Vanzetti, Hiss or the Scottsboro Boys were really guilty as charged, although perhaps we should care more than we do. Even if, under code-name Blin, Stone did occasionally meet and share names and phone numbers with KGB agent Oleg Kalugin, who was, remember, posing as a press attaché, he hardly possessed or could transmit information damaging to national security, his sole source of documentation being the Congressional Record and other available government documents — all public records which any spook could have read without the assistance of an American reporter.

And as someone who, before Glasnost, frequently dined and exchanged sources with Tass correspondents, I really can’t understand what all the fuss is about. That was simply part of our work — sharing information with fellow reporters. So what if it was with people who, as it turned out, weren’t really press attaches? It still wasn’t spying. Nor was it in Stone’s case, if there is a case at all. Those innocent lunches, most of them at Harvey’s (J. Edgar Hoover’s favorite restaurant, where Hoover was once seated next to Joe McCarthy in plain sight of Stone and Kalugin), should never have been considered treasonous, given the fact that Stone’s motivations and the Russians’ were, at the time, both anti-fascist, as was the expressed foreign policy of the U.S. government. A more reasonable conclusion would be that Izzy Stone was merely tweaking power. Otherwise he would have met Kalugin in a parking garage.

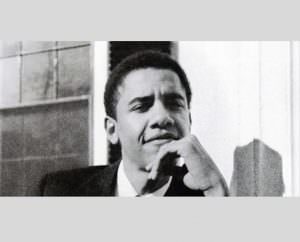

I had to wonder, as I read this book, what Izzy would have thought of it and, even more so, what he would be up to were he alive today. He’d be blogging, of course, hourly not weekly. And he would certainly be arguing back against his biographers — and his hagiographers. But what would he make of Barack Obama and the crisis that capitalism faces? Surely he would be as glad and surprised as most of us that an African-American had reached the White House, but I imagine he would be after the president for allowing Wall Street to maintain such close ties to the Treasury, and he would be pushing the administration to accelerate troop withdrawal from Iraq, legislate a single-payer health care system, appoint some fellow radicals to the Supreme Court and, of course, he would still be looking for lies … and finding them.

Would that he were still alive and kicking.

|

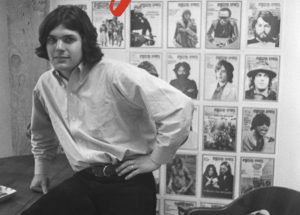

Mark Dowie, a founder of Mother Jones magazine, is an award-winning journalist and author of several books, including “Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century,” “American Foundations: An Investigative History” and the just-published “Conservation Refugees: The Hundred-Year Conflict Between Global Conservation and Native Peoples” (MIT Press). |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.