Mark A. Fischer on Joe Torre

Just how important is a baseball team's manager to how well a team performs? A new book by one of baseball's giants attempts an answer. You be the judge.

Does it matter who manages a baseball team? Leaders are important in life. So it should be true that baseball managers make a crucial difference in determining which teams win — and which lose. But how do we know for sure? Statistics aren’t of much use in distinguishing a manager’s success apart from the performance of his players. Does a great manager cause his team to win, say, four more games a year than it would without him? Ten more games? You really can’t look it up.

Casey Stengel was famously fabulous with the Yankees when he had Mickey Mantle in the outfield; not at all so much in the hopeless days when the Amazin’ Mets’ Marvelous Marv Throneberry prowled first base. In other words, absent gross incompetence on the part of the manager, will a team stocked with great players — whether idiots or savants — win the pennant regardless of who is the manager?

James Click, in his insightful piece “Is Joe Torre a Hall of Fame Manager?” (from the book “Baseball Between the Numbers,” Basic Books, 2006), wrote that Joe Torre is likely to enter the Hall of Fame. But he concluded that objective performance statistics aren’t the reason why.

From 1996 to 2007, Yankees skipper Joe Torre was the outward manifestation of calm leadership, protective of his players, gregarious and charming with the media (many guessed that after his managing career with the Yankees he would become a sportscaster — an occupation that he held for the five years between his managing the Atlanta Braves and the St. Louis Cardinals. Torre’s Yankees won four World Series (1996, 1998-2000). Inside Torre was a sensitive and judgmental mind, an insecure man in an insecure profession.

From the manager’s perspective there’s much to worry about — and not just his players. Looking outside at the baseball world from inside the manager’s office, it seems that diva players, owners, general managers, agents, reporters, fans and others can be devoted to making a manager’s life unhappy. It may be that this phenomenon is most acute when working for George Steinbrenner and his sons.

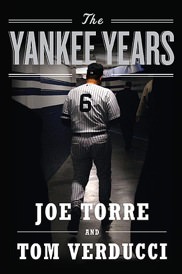

Managers, judging from “The Yankee Years,” attributed to Joe Torre and Tom Verducci (more about authorship later), usually are happy when their players play in the field and much less so at other times. Torre’s more recent experiences dominate the book, and these seem bittersweet, and, on occasion, just plain bitter.

|

To see long excerpts from “The Yankee Years,” click here. |

Torre’s observations are expressed in the third person, or attributed to Torre in quotation marks. Is Torre being ironic, postmodernist or just distancing himself from his own book? I’m pretty sure it’s the third. Baseball guys seem to lack irony.

Many sports books are credited “as told to … ” Babe Ruth’s book was “as told to Bob Considine.” Torre has, it would appear, told this book to both himself and Tom Verducci. As a result, this otherwise informative and readable book lacks the intensity and authenticity that Torre’s own voice would have provided. The book opens with a sentence so detached it seems as if George Steinbrenner’s decision-making that made Torre the Yankees manager for the 1996 season is being analyzed from outer space rather than by the book’s author: “Joe Torre was the fourth choice.”

Because Torre had been critical of pitcher David Wells tattling about locker room baseball tales in Wells’ own book, Torre’s disclosure of inside stories inside baseball comes as a bit of a surprise. But Torre’s book is in the long line of books telling it all, pretty much beginning with Jim Brosnan’s “Long Season” in 1960 and, of course, Jim Bouton’s revelatory “Ball Four” a decade later.

Torre felt in his later Yankee years, with good reason, very insecure about keeping his job. All baseball managers should know that they are hired to be fired. Boston’s Terry Francona recently said that had not Dave Roberts stolen second base in game four of the 2004 playoffs, he, Francona, would have been out of a job (and he’s probably right about it). Torre seems to have believed that as a result of his team’s great success in the mid-1990s he was owed the special protection of long-term tenure. If he had been the manager of the Royals or the Diamondbacks he might have sensed the constant shadow of termination with more equanimity. It’s an old baseball observation that it’s easier for a general manager to fire the team’s manager for a losing season than to fire the team. Torre’s awareness of his job mortality hovered over the last few of his Yankee years.

Baseball is different from many other sports. The defense controls the ball. Methodically detailed playbooks (the ones that football and basketball coaches devise) describing set plays aren’t quite so useful in this game. The baseball season is a long one. Baseball managers tend not to be as fiery as their football counterparts (Billy Martin and Lou Pinella are the exceptions and not the rule). Screaming, inspirational clubhouse speeches lose their impact in the course of the 162-game season.

Instead, baseball mandates attention to subtleties. Ted Williams’ top batting tip was “get a good pitch to hit.” His Zen lesson is true in baseball and in life. The Splendid Splinter’s lesson suggests the limits every player faces in controlling the outcome of a game in which the pitcher sets the ball in play. It’s a hard game. A star player who hits .333 is failing to get a hit two-thirds of his times in the batter’s box.Managers have to expect the unexpected. Now the manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Torre has new challenges. When Manny Ramirez, the crazy genius rock star of right-handed hitting, is outed for using illegal somethings (and as a result temporarily suspended from baseball), it is deeply disappointing. But it’s ultimately not shocking. Geniuses are entitled to latitude, cheaters aren’t. (Torre’s Dodger player Manny will no doubt be the subject of a chapter in Torre’s “The Dodger Years,” if he gets around to writing it. Torre’s steadiness would seem a good antidote to Manny’s attitude.)

Torre heaps praise or dirt, as he sees it, on his former players. In “The Yankee Years,” we learn that Derek Jeter is every bit as classy, and as much a stand-up guy, inside the clubhouse as he is on the field. A-Rod is called “A-Fraud” by teammates. Johnny Damon fights off demons and was (surprisingly) disliked by his teammates because they saw him as dragging down the team. Kyle Farnsworth can sit “in the corner of the tiny run-down trainers’ room in the visiting clubhouse” of Shea Stadium and cry (there is crying in baseball, after all!). It’s reassuring to learn that Paul O’Neill was to his manager the gritty gamer the fans thought he was. Torre became more and more uneasy with Yankees General Manager Brian Cashman. Torre, who prizes heart very much, wanted Bernie Williams to stay on the team in 2007; Cashman overruled him. And there’s just a little insight as to Torre’s perennial trait of overworking his middle relief staff.

Pitcher Kevin Brown is held out for particular scorn. In deciding who should be the Yankees pitcher in the seventh game against the Red Sox in the 2004 playoffs, Torre’s book says, “That left Kevin Brown, the 39-year-old pitcher with the bad back, the carrier of bad karma, and the guy who looked hurt and ineffective in Game 3 in only his fourth game since breaking his left hand in a childish fit of anger.” Hard to find a compliment for Brown in that sentence.

It’s one thing to lose while trying. It’s another to quit. In a May 2007 game against what were the then-Devil Rays (today known as the Rays), at the end of the first inning, having given up six runs, Brown told Torre, “I’m done!” Torre found Brown curled up in a corner of a storage area in the back of the clubhouse. Brown said, “I’m going to go home.’ ” And he didn’t mean home plate. Torre somehow managed to convince Brown to go back to the mound.

In the chapter entitled “The Attack of the Midges,” Torre says that his worst managerial mistake was failing to demand that the Yankees leave the field in game two of the 2007 Division Series. Why? An onslaught of midges swarmed the Yankees and surely distracted pitcher Joba Chamberlain. Cleveland hurler Fausto Carmona, in contrast, even though his neck was covered in midges, thrived in the game. Maybe Cleveland manager Eric Wedge’s best decision ever was to keep Carmona and his team in the game, midges or not. In other words, two managers made the same decision. For one manager it worked, for the other it didn’t. Despite its considerable insights, Sabermetrics, a science of baseball studies, couldn’t have predicted which pitcher was more midge-proof.

For the Yankees, only a World Series marked a successful season. By that standard, 2007 was a failure because the Yankees exited early in the playoffs to the Indians. The tension in Torre’s relationship with the Steinbrenner family and with Cashman had reached the breaking point in the offseason. The Yankees offered Torre a one-year contract with bonuses for performance. Torre demanded two years. Torre believes that Cashman let him down. As the negotiations ended (he did his own negotiating — no Scott Boras for Joe Torre), he realized, “The allies of Joe Torre had dwindled to zero.” The negotiations were over and Joe Girardi would replace Torre.

Was Torre, in his Yankee years, just lucky to be the right man at the right time? When he was blessed with Paul O’Neill and Derek Jeter in his prime the team won championships. When fortune burdened him with Carl Pavano and the perplexing A-Rod he did not (nor had he won a pennant with the other teams on his managerial résumé, the Mets, Braves and Cardinals).

At a time when America so deeply places its hope for progress in its new president, and CEOs are acutely held responsible for their enterprises, it’s hard not to believe that a leader makes a difference for better or worse. Intuitively, baseball fans respect Torre. We believe that he is one of the game’s very best managers, for which the longtime support by his best players is convincing inferential proof. We are surer, however, that it’s the players who ultimately win or lose the game. The best way for any manager to win is to get good players to hit, pitch, field and run for him.

|

Mark A. Fischer is a Boston-based new media lawyer, copyright law professor and Red Sox season ticket holder. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.