Mario Vargas Llosa: A Celebration

With the author having turned 82 this week, we take a look at his life's work, including two new editions. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

“The Neighborhood: A Novel” and “Sabers and Utopias: Visions of Latin America”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Books by Mario Vargas Llosa

Sometime in this decade, or no later than the next, Mario Vargas Llosa will be referred to, routinely, as the greatest writer of his time, or perhaps the greatest man of letters of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Surely his only rival for these unofficial titles would be his exact contemporary, V.S. Naipaul, also accomplished in both fiction and nonfiction.

What is curious is that at no time in Vargas Llosa’s career—which began in 1963 and continues with the publication of his 18th novel, “The Neighborhood,” and essays on Latin America, “Sabers and Utopias”—so few have argued his case. Though awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010, the honor seemed tardy by a decade or even two.

Click here to read long excerpts from “The Neighborhood” and here for “Sabers and Utopias” at Google Books.

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Vargas Llosa is a novelist of greater imaginative gifts than Naipaul, who was given the Nobel in 2001. Gabriel Garcia Marquez won in 1982, a fact tinged with irony since his work was first known by many American and European critics through Vargas Llosa’s 1971 appreciation, “Story of a Deicide.”

A likely reason why many were slow to come to Vargas Llosa’s work is politics. The Nobel committee has always been reluctant to recognize writers of a conservative bent—Nabokov, Evelyn Waugh and even the man who sparked the Latin boom, Jorge Luis Borges, were all slighted. Vargas Llosa was never a conservative; his moral and philosophical beacon has always been Albert Camus, who broke with the European orthodox left in the early 1950s. In his rich and funny 1993 memoir, “A Fish in the Water,” he wrote, “There was practically no way in which an intellectual of a country such as Peru was able to work, to earn his living, to publish, in a manner of speaking to live as an intellectual, without adopting revolutionary gestures, rendering homage to the socialist ideology, and demonstrating in his public acts—his writing and his civic activities—that he belonged to the left.”

Peruvian intellectuals, he said, though he surely meant intellectuals from all Latin countries, lived in a “moral hemiplegia … repeating on the one hand, in public, an entire defensive logomachy—a sort of countersign in order to assure their posts within the establishment—which corresponded to no intimate conviction.” When a writer lives in this way, “the perversion of thought and language becomes inevitable.”

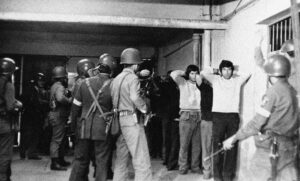

In 1971 he broke with the left and became a conscience of liberal thought, organizing a coalition of Latin, North American and European writers (among them Octavio Paz, Susan Sontag and Jean Paul Sartre) in a public denunciation of the Castro regime’s oppression of Cuban poet Heberto Padilla and the Stalinist-type show trial he was subjected to. Sartre, in particular, was shamed into a public condemnation of a Communist government that he had never made against Stalin’s Russia.

Moving toward the middle cost Vargas Llosa some support from the intelligentsia. From a 1985 essay, “Nicaragua at the Crossroads”: “For a reason as mysterious as the street directions in Managua, the defense of freedom of expression, elections, and political pluralism gain one the reputation, among Latin American intellectuals, of being right wing.” One might add among some American and European intellectuals as well.

Politics may have led to a break with his longtime friend, Garcia Marquez. In 1976, Vargas Llosa punched him out at a chance meeting at a Mexico City movie theater, the only known bloodletting between Nobel Prize winners (well, since Pearl Buck KO’d Hemingway in three rounds at the Garden). The altercation may have been started by something Garcia Marquez said about Vargas Llosa’s wife, then exacerbated by politics.

Since then, the two have often been compared and contrasted. Vargas Llosa has never written a novel as epochal as “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” certainly the most influential work of fiction yet produced by a Latin American writer. Without “Solitude,” the Latin boom may never have happened, or if it did, might have occurred in a rainforest unheard by the rest of the world.

Vargas Llosa’s oeuvre, though, displays a greater range of styles and themes. To select three of the most seemingly disparate: “Conversation in the Cathedral” (1969), his most critically celebrated novel, is a dark tangle of sex, politics and Peruvian history. It’s hard to reconcile the author of that novel with the one who wrote the hugely popular “Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter” (1977), about a TV writer of radio soap operas who takes his ideas from master plots of great novels. “Aunt Julia” surely vies with Kingsley Amis’ “Lucky Jim” and Evelyn Waugh’s “The Loved One” as the funniest novel since World War II.

And there are novels that even aficionados have yet to discover, my favorite of which is “The Dream of the Celt” (2010). Written when Vargas Llosa was 74, it is a fictional biography of real life, enigmatic Irish freedom fighter Roger Casement, who spent much of his life as an activist for human rights in Africa and South America and died in a British prison in 1916.

No other modern writer would have been capable of writing three such different novels, and yet there are common threads: the unrelenting fight for Western concepts of democracy and human rights, and how the melding of Western literature and native traditions have produced a new culture in the Americas.

Now in his 80s, Vargas Llosa is no longer wrestling with the deep dish issues of his earlier work; he has become something of a social satirist. “The Neighborhood” reads like it was ripped from the pages of Donald Trump’s favorite supermarket tabloid. It takes place in 21st century Lima where “if it hadn’t been for terrorism and kidnapping … one lived very well.” Enrique, a Peruvian industrialist, is blackmailed by a sleazy editor “with a rat-like little smile” who runs a scandal sheet and has pictures of him in a hotel room with prostitutes.

The murder of the verminous editor kicks off events that reach the highest levels of government, including a stealthy police operative who declares, “The only thing I ask of my collaborators is loyalty. A doglike fidelity.” If you see any similarities between “The Neighborhood” and the lead stories on cable news, it’s because Vargas Llosa, 55 years after his first novel, still has an ear to the ground of the international political climate.

In The New York Times a couple of weeks ago, Dwight Garner wrote that “ ‘The Neighborhood’ isn’t very good. It doesn’t rank anywhere near the five novels that made his reputation.”

That’s the problem with still being a great novelist at Vargas Llosa’s age: The books he wrote when he was younger, which many overlooked at the time, are now used as clubs to beat his newer ones with. I’d wager the box office of “Black Panther” that if “The Neighborhood” were released under a name other than its author’s, it would be praised as the work of a fresh, invigorating new talent.

Garner had even harsher words for Vargas Llosa’s essays, “Sabers and Utopias”: “This book is, sad to say, all but unreadable. Vargas Llosa’s op-ed voice is not his best voice (it is few people’s best voice) and these pieces … are essentially dead on the page.” Actually, I would say that the nonfiction of most important American writers of the last 60 to 70 years—say, Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal, James Baldwin and Susan Sontag—has been their best voice.

As for Vargas Llosa’s op-ed voice, I agree with Clive James (in “Cultural Amnesia”) that his true strength “is undoubtedly in the essay. His collected essays written between 1962 and 1982 make the perfect pocket book for getting up to speed with how the bright, baby-boom students of Latin America won their way towards a solid concept of liberal democracy.”

“Sabers and Utopias” takes us from 1982 to now, attending to matters both Latin and global:

- “Funeral Rites for a Tyrant” contains a ringing argument as to why “political democracy without economic development does not last.”

- “The Logic of Terror” explicates the mind of a terrorist in terms that complement Camus’ “The Rebel.” The terrorist prefers dictatorship “with its rigid control of information, its omnipresent police, its implacable persecution of all kinds of dissidence and criticism” to democracy, whose formal freedoms he regards as “a dangerous fraud, capable of deactivating the rebellion of the masses against their condition … taking the revolution one step back.”

- In “Down with the Law of Gravity!” globalization “is not, by definition, good or bad: it is a reality of our time that has come out of a sum of factors, technological and scientific development, the growth of businesses, capital and markets, and the interdependence that this has created among the world’s different nations.”

- From “Elephant and Culture”: “Nationalism is the culture of the uneducated, and of these, there are legions.”

- Julian Assange and Ecuadorean tyrant Rafael Correa “are made for each other. … Isn’t it curious that WikiLeaks made it such a priority to reveal the confidential documents of free countries where, in addition to freedom of the press, there exists a legality worthy of the name, instead of doing so with dictatorships and despotic governments?”

- In Latin countries, borders “do not signal true differences” and “in the field of culture, Latin American integration has come to be something real, a product of experience and necessity.”

It’s hard to imagine that any American or European writer voicing such opinions would be called dead on the page.

Vargas Llosa writes of writers you have read such as Borges (“His stories, essays, and poems are, surely, the ones that have had the greatest impact on other languages of any contemporary author of our language”), writers you have perhaps heard of but not read such as Guillermo Cabrera Infante (“No modern writer in our language, perhaps with the exception of Macando’s inventor [Garcia Marquez], has been capable of creating a local mythology with so much strength and color as this Cuban has”) and writers you have probably not heard of but should have, such as the Nicaraguan poet Ruben Dario (“birth mother and father” of modern Spanish American poetry).

In “Notes on the Death of Culture” (2015), Vargas Llosa lamented that “critics are a dying breed, to whom nobody pays attention unless they also turn themselves into a form of entertainment and spectacle.” If he is wrong, it will be because serious readers no longer read writers such as Vargas Llosa. If he’s right, the few critics who are left may remember him as the last public intellectual.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.