Malarial Mosquitos Are Flying Higher

With many higher regions warming due to climate change it's likely that mosquitoes carrying malaria will enlarge their territories.

By Tim Radford, Climate News NetworkThis piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

LONDON — Things are looking up for the little parasite that infects 200 million people a year, and kills more than 600,000 of them.

As global temperatures rise, so will the altitude at which the Anopheles mosquito and its plasmodium parasite can survive, and so will the numbers at risk from malaria.

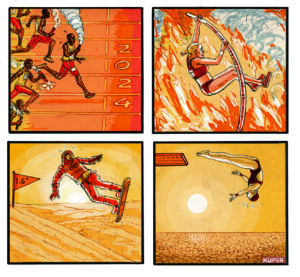

The global war against malaria has always been an uphill struggle, but populations in highland regions have usually been safe, because the parasite cannot replicate at low temperatures.

Disease spread

But Amir Siraj of the University of Denver in Colorado in the US and colleagues in the UK and Ethiopia report in the journal Science that they’ve started to consider the effect of climate change on the spread of the disease.

Projections of hazards such as these are difficult: the likelihood of infection can depend on steps civil, national and international health authorities may take, the preparedness of communities depends on spraying programmes and the availability of drugs, and the numbers at risk alter as populations grow and economies develop.

All malaria needs is somewhere warm and wet, and a steady supply of potential hosts. The disease was once endemic in mild, low-lying or marshy areas of Europe (the name comes from the Italian mal aria, or bad air).

It can be controlled by spraying, and by public education. But it remains an enduring hazard in Africa, parts of Asia and South America. Upland communities, however, have tended to be safe.

Data search

But the Denver team decided to forget about all the complex possibilities and just look at some very precise data from 124 municipalities in Antioquia in western Colombia between 1990 and 2005, and 159 administrative units in the Debre Zeit region of Ethiopia from 1993 to 2005.

They reasoned that a match of seasonal temperatures and reported cases would tell them what to expect.

Sure enough, they found that during warmer years, there were more reported cases of malaria in both countries. The “median altitude” at which cases were registered shifted accordingly with annual temperatures. That gave them enough information to consider some alarming possibilities.

In a previous study, scientists predicted that a 1°C rise in global average temperatures could bring an additional three million cases a year in Ethiopia among children under 15. As average temperatures rise, so will the numbers of potential victims soar, and so will the need for investment in mitigation and insect control.

“With progressive global warming, malaria will creep up the mountains and spread to new high altitude areas,” said Menno Bouma of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, one of the authors.

“And because these populations lack protective immunity, they will be particularly vulnerable.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.