|

To see long excerpts from “MaddAddam” at Google Books, click here.

|

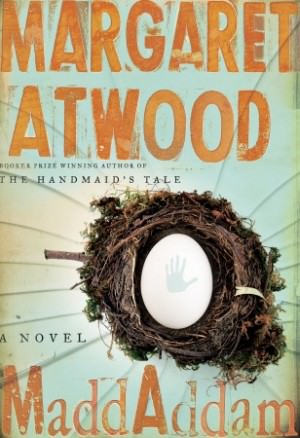

“MaddAddam”

A book by Margaret Atwood

If you haven’t already read Margaret Atwood’s “Oryx and Crake” (2003) and “The Year of the Flood” (2009), you shouldn’t read “MaddAddam,” even though it is wonderfully entertaining and just about everything you could want in a novel. This is the concluding volume in a “dystopian trilogy” — a vision of global disaster in the not too distant future — and while it can certainly be enjoyed without knowing the earlier books, why would anyone start here? You wouldn’t watch “Return of the Jedi” as your first “Star Wars” movie, would you? Go out and buy all three installments and begin at the beginning.

That said, in a prefatory note, Atwood does summarize “The MaddAddam Trilogy: The Story So Far.” In those first two novels, we were introduced to a world where the HelthWyzer Corporation acts as the government. Its top researchers and their families live in fortified compounds that separate them from the vast underclass and from pleebrat gangs such as Asian Fusion and the Tex-Mexes.

The police have been replaced by HelthWyzer’s private security force, the CorpSeCorps, and its storm troopers keep the peace by simply doing away with undesirables and anyone who opposes the corporation’s activities. More often than not, the victims’ bodies, usually minus some important organs, are ground up with sundry other ingredients to make the addictive SecretBurgers. Other suspicious franchises include the beverage chain Happicuppa and the beauty salon AnooYoo.

In this frightening, but not wholly unfamiliar world, Atwood focuses on the interactions of a small group of rebels: the brilliant but unstable genetic scientist Crake; his sidekick, Jimmy, and Oryx, the woman they both love; a bioterrorist group known as MaddAddam, which communicates through a computer game called Extinctathon; and a pacifist religious cult called God’s Gardeners.

The Gardeners are led by the saintly Adam One, who has long foretold the coming of a Waterless Flood that will cleanse the sordid and polluted Earth. Until that day, the Gardeners are protected by Zeb, an eco-terrorist who teaches Urban Bloodshed Limitation, “which was street fighting viewed from a loftier perspective.” Such survival techniques come in handy when young women in the group — Toby, Ren and Amanda — are hunted by the Painballers, the brutal winners of a “reality” television program that pits vicious murderers against each other until only one is left alive.

But all this is in the past. Early on in both “Oryx and Crake” and “The Year of the Flood,” we know that the foretold pandemic has wiped out most of humanity. Genetically altered animals, such as the preternaturally intelligent pigoons, now roam wild. Painballers prey on the few survivors from MaddAddam and God’s Gardeners. Not least, in the Paradice dome — sometimes referred to as the Egg — Crake has developed and released a lab-grown and childlike humanoid species called the Crakers. Think of H.G. Wells’ Eloi from “The Time Machine.”

In her trilogy’s first volume, Atwood concentrated on Crake, Oryx and Jimmy, and in the second, on Ren, Toby and Amanda. This last one presents — through lengthy flashbacks — the earlier lives of Adam One and Zeb while also depicting the struggle for human survival in a now-devastated world.

“MaddAddam” opens where its two predecessors converged: on the kidnapping of Amanda by two Painballers, who repeatedly rape and torture the young pleebrat. She is rescued by Toby and Ren, with the help of a feverish Jimmy, just when these cannibalistic psychopaths are getting ready to eat her. But when the Crakers unexpectedly appear, a melee ensues that allows the two Painballers to escape. Their eventual return for vengeance is almost certain.

Does all this sound totally grim, “Brave New World” meets “Blade Runner” meets “Escape From New York” meets “The Road Warrior”? It’s not. Atwood’s three-part masterpiece is one of those stories that are thrilling and funny and romantic and touching and, yes, horrific by turns and sometimes all at once. Best of all, “MaddAddam,” like the final volumes of many other trilogies, draws multiple plot strands together, showing how seemingly disparate elements from the earlier books are really deeply interconnected. For instance, the upscale sex club Scales and Tails turns out to be a lot more than we initially thought it to be.

As before, Atwood’s touches of humor and satire soften her vision of the rancid pre-plague world of Sewage Lagoons and Seksmarts. Zeb’s sadistic father — a minister of the Church of PetrOleum — inveighs against “the Enemies of God’s Holy Oil” with such hate slogans as “ ‘Solar Panels Are Satan’s Work,’ ‘Eco Equals FreakO,’ ‘The Devil Wants You to Freeze in the Dark,’ ‘Serial Killers Believe in Global Warming.’ ” Pop groups are named the Luminescent Corpses and the Bipolar Albino Hookworms. One hacker, on the run, avoids the Internet because of “DORCS: digital online rapid capture specialists.” When an assassination is botched, it results in “proof” that the Sasquatch exists. Many of Atwood’s jokes are mildly obscene, like the T-shirt that Zeb uses as a disguise: “Organ Donor, Try Mine Free.”

As the eight or 10 plague survivors interact, fearful of Painballers and puzzled by the purring Crakers, Atwood depicts the growing love of Toby for Zeb, her jealousy of the young, bedroom-eyed Swift Fox, and her deepening affection for the endearing Craker child Blackbeard, whom she teaches to write. Toby is also obliged to tell stories to the Crakers, and to do so must don a sacred Boston Red Sox hat, eat an undercooked fish and consult the blank face of a broken wristwatch. Many of her stories are based on the earlier, almost picaresque adventures of Zeb, who, we gradually learn, has links to the young Crake, knew the old medicine woman Pilar when she was a senior scientist at Helthwyzer, and is Adam One’s beloved younger brother.It’s clear from the above that Atwood embraces coincidence as boldly as did her fellow Canadian novelist Robertson Davies. But she notably excels in her mastery of varying registers of spoken English. Describing Zeb’s hacker life, she might pass for a cyberpunk. Her Crakers mimic the relentless questioning of inquisitive 3-year-olds. At the thought of a Twinkie, Ren gushes, “They were so retro-nouveau revival!” Though practically a god to the Crakers, Jimmy is profane and thoroughly ungodlike in his speech. As he advises Toby: “I hear they’re fanboys for Zeb these days. Stick with that plotline, it’s got legs. Just keep them from finding out what a bogus fraud everything is.”

Besides being a cautionary tale and a brilliant work of social science fiction, “MaddAddam” is also, in its relationship to its predecessors, something of a metafiction. As Atwood writes, “There’s the story, then there’s the real story, then there’s the story of how the story came to be told. Then there’s what you leave out of the story. Which is part of the story too.”

As such, “MaddAddam” is a marvel of sustained artistic control, neatly reshuffling pieces and filling in all the gaps from the two earlier books, including those we weren’t aware of, before rising to a deeply moving, if not wholly unforeseen, conclusion. It is further proof that Margaret Atwood, even if she doesn’t wear a sacred Red Sox cap, is an utterly thrilling storyteller and not just Canada’s greatest living novelist.

©2013, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.