|

To see long excerpts from “Tennessee Williams” at Google Books, click here.

|

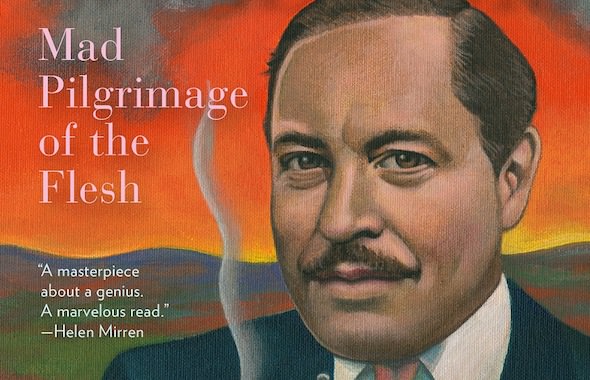

“Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh”

A book by John Lahr

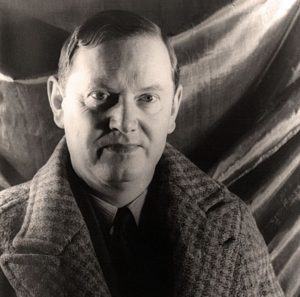

John Lahr begins his fascinating new biography in medias res: on March 31, 1945, the opening night of 34-year-old Tennessee Williams’ first Broadway hit, “The Glass Menagerie.” It’s an appropriate place to start “Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh,” for as Lahr asserts, Williams “was the most autobiographical of American playwrights,” and “The Glass Menagerie” is the most nakedly autobiographical of his plays.

The play’s narrator, Tom (Williams’ real name), is trying to cope with his self-deluding mother and his fragile sister after his father has abandoned them. The mother, Amanda, is a barely disguised version of Williams’ own mother, Edwina, who bristled with indignation when Laurette Taylor, the actress playing Amanda, asked after the opening night of the Chicago tryout, “Well, Mrs. Williams, how did you like yourself?” The sister in the play, Laura, has a physical handicap, a limp, which Williams substituted for the mental illness of his real sister, Rose. Even the father’s absence reflects the frequent periods when his bullying salesman father — Cornelius Coffin Williams — known as “CC,” would go on the road, leaving Tom, Edwina and Rose at one another’s mercies.

Eventually, Rose’s mental instability and Edwina’s reaction to it received a more explicit treatment in Williams’ play “Suddenly Last Summer,” which works out what Lahr calls “Williams’ grief and guilt over his sister, Rose, as well as his anger at Edwina for deciding to allow a bilateral prefrontal lobotomy to be performed on her without informing him in advance.” And even Williams’ father, though absent from “The Glass Menagerie,” had his turn on stage, inspiring Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” whose title was taken from one of CC’s colorful expressions.

But Williams revealed less of himself in his first Broadway hit than he did in the next one, “A Streetcar Named Desire.” As Elia Kazan, the play’s director, put it, “Tennessee Williams … is Blanche. And Blanche is torn between a desire to preserve her tradition, which is her entity, her being, and her attraction to what is going to destroy her traditions.” Sensitive but self-destructive, both Blanche Dubois and Tennessee Williams depended on the kindness of strangers. But Williams also depended on, and received, the patience and understanding of friends and colleagues.

Among these was Kazan, whose relationship with Williams was, in Lahr’s view, an attraction of opposites: “Williams was shy, standoffish, and fragile; Kazan … was brash, extroverted and powerful. Williams was discombobulated; Kazan was a fixer.” Under Kazan’s direction, “Streetcar” became one of the landmarks of American theater, and he took an even greater role in helping shape Williams’ other Pulitzer-winning play, “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” guiding the playwright, who was sometimes reluctant to make Kazan’s changes, into essential revisions. Their collaboration, Lahr says, “was the most influential in twentieth-century American theater.” Kazan “rallied him out of his writing blocks, challenged his melodramatic excesses, chivied him to work for greater depth, and allowed his imagination to soar.”

But Williams might not have had a career in the theater at all if it hadn’t been for Audrey Wood, who became his agent in 1939, having discovered something in his early writing that she nurtured into maturity. “No playwright-agent relationship in American theater history had … a longer or more glorious story than Williams’ partnership with Wood,” Lahr comments. His growth was in large part dependent on “her keen critical eye, her deep knowledge of the theater, and her understanding of his complex personality.”

A third force, a more volatile one, during the most creative period in Williams’ life was his lover and personal secretary, Frank Merlo, whose tales of his Sicilian-American family Williams drew upon in “The Rose Tattoo.” Merlo is also the model for that play’s ebullient Alvaro Mangiacavallo, whose wooing of the widow Serafina is seen by Lahr as “a slapstick simulacrum of Williams’ relationship with Merlo.” Despite the hectic, even violent nature of their relationship, Williams and Merlo stayed together for almost 14 years, and the Key West home they shared gave Williams’ life a much-needed center and stability.

Over 16 years, Williams’ plays won a Tony Award, two Pulitzer Prizes and four New York Drama Critics’ Circle awards. He accumulated a small fortune, much of it from the sales of film rights to his plays. And in Lahr’s words, he changed “the shape and the ambition of the American commercial theater” with a body of work drawn from his inner life that resonated particularly well with the American mood from the end of World War II to the beginning of the Vietnam War.

Then, in 1961, Williams’ great period ended with the opening of “The Night of the Iguana.” “In the twenty-two years of life that remained to Williams,” Lahr observes, “he would have seven more Broadway openings, but ‘Iguana’ would be his last hit.” A year earlier, Williams and Kazan had gone their separate ways when Kazan decided not to direct Williams’ “Period of Adjustment.” Williams’ alcoholism had become exacerbated by the amphetamines prescribed by Dr. Max Jacobson, the pharmacologist to the stars known as “Dr. Feelgood,” and Williams became subject to paranoid delusions that finally caused Merlo to move out. Merlo died of lung cancer in 1963. In 1971, Williams completed the break with his past by abruptly and irrationally firing Wood, his agent for more than 30 years.For the rest of his life, Williams was prey to sycophants and enablers, including Maria St. Just, a Russian-born social climber, whose marriage to an English aristocrat allowed her to style herself Lady St. Just. Her hold over Williams extended even beyond his death in 1983, whereupon she became his de facto literary executor, even though she wasn’t named as such in his will. She exerted arbitrary control over productions of the plays and frightened off biographers. And when theater owner Rocco Landesman wanted to name what is now the Walter Kerr Theatre for Williams, St. Just demanded that Landesman also produce a revival of Williams’ play “Orpheus Descending” on Broadway. “Tennessee would have had the most beautiful theater in New York named after him,” Landesman said. “But I wouldn’t submit to blackmail.”

Lahr gives us a sense of the ebb and flow of Williams’ life, exercising a critic’s keen eye on the plays, a novelist’s gift for characterization, and a historian’s awareness of the way a changing American society colored his work. The result is almost as much a biography of the plays as of the playwright — a book that lets the life illuminate the work and the work illuminate the life.

Charles Matthews is a writer and editor in Northern California.

©2014, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.