Longtermism and Eugenics: A Primer

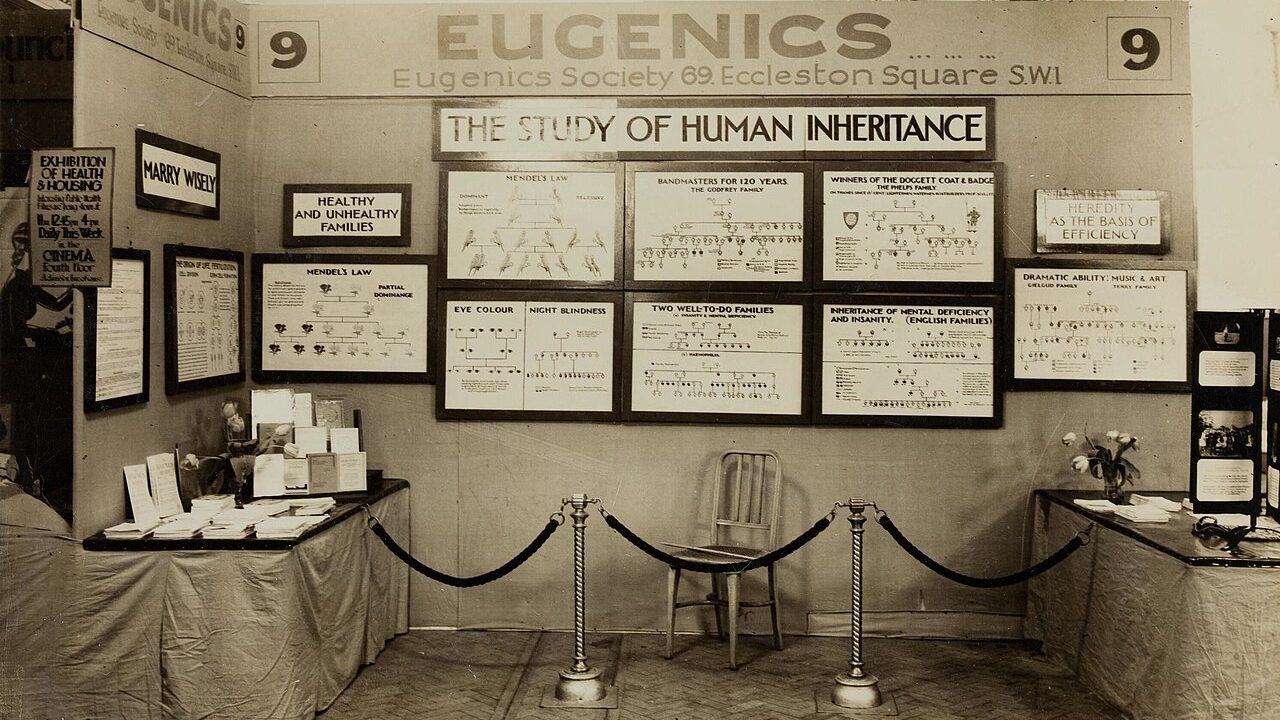

The intellectual lineage of Nick Bostrom’s retrograde futurism. Eugenics Society Exhibit (1930s). Image from Wellcome Library. Photo: Wellcome Collection / CC BY 4.0

This is Part of the "Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century: New Names, Old Ideas" Dig series

Eugenics Society Exhibit (1930s). Image from Wellcome Library. Photo: Wellcome Collection / CC BY 4.0

This is Part of the "Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century: New Names, Old Ideas" Dig series

My first article for The Dig claimed that the ideology of longtermism is in important respects another iteration of the “eternal return of eugenics.” Not only can one trace its genealogy back to the 20th-century eugenics tradition, but the longtermist movement has significant connections with people who’ve defended, or expressed, views that are racist, xenophobic, ableist and classist. Indeed, my point of departure was an email from 1996 that I’d come across in which Nick Bostrom, the Father of Longtermism, wrote that “Blacks are more stupid than whites,” and then used the N-word. He subsequently “apologized” for this email without retracting his claim that certain racial groups might be less “intelligent” than others for genetic reasons.

I aimed to show that when one wanders around the neighborhoods that longtermism calls home, it’s difficult not to notice the attitudes mentioned above almost everywhere. At the very least, leading longtermists have demonstrated a shocking degree of comfort with, and tolerance of, such attitudes. For example, despite their deeply problematic views about race, Sam Harris and Scott Alexander are revered by many longtermists, and longtermists like Anders Sandberg have approvingly cited the work of scientific racists like Charles Murray.

This is alarming because longtermism is an increasingly influential ideology. It’s pervasive within the tech industry, with billionaires like Elon Musk calling it “a close match for my philosophy.” Perhaps even more concerning is the fact that longtermism is gaining a foothold in world politics. The U.N. Dispatch reported in August 2022 that “the foreign policy community in general and the United Nations in particular are beginning to embrace longtermism.”

My article covered a lot of ground, and some readers suggested that I write a brief explainer of some of the story’s main concepts and characters. What follows is a primer along these lines that I hope provides useful background for those interested in the big picture.

Eugenics

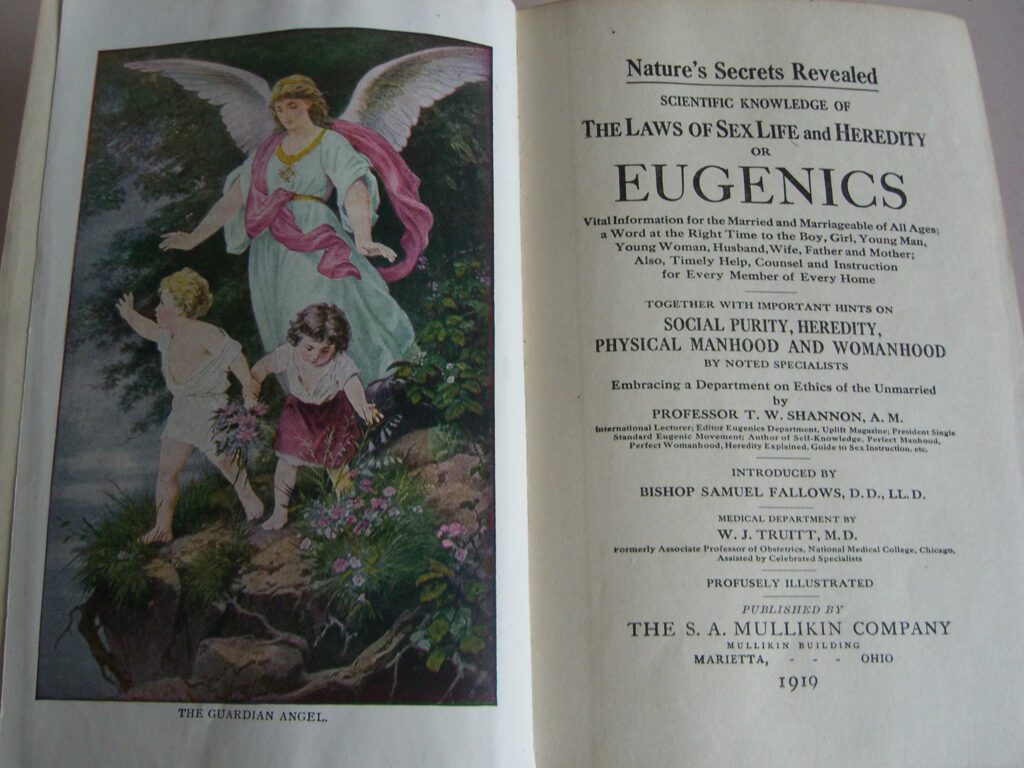

The word “eugenics” was coined by Charles Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, in 1883, although the idea was popularized earlier in his 1869 book “Hereditary Genius.” The word literally means “good birth.” There are two general types of eugenics: positive and negative. The first aims to encourage people with “desirable traits,” such as high “intelligence,” to have more children. This was the idea behind “better baby” and “fitter family” contests in the United States during the early 20th century. The second strives to prevent what eugenicists variously called “idiots,” “morons,” “imbeciles,” “defectives” and the “feeble-minded” (often identified using IQ tests) from reproducing. This is what led to the forced-sterilization programs of states like Indiana and California, the latter of which sterilized some 20,000 people between 1909 and the 1970s (yes, that recently).

Although the modern eugenics movement was born in the late 19th century, its influence peaked in the 1920s. During the 1930s, it was taken up by the Nazis, who actually studied California’s eugenics program in hopes of replicating it back in Germany. Despite the appalling crimes committed by the Nazis during World War II, eugenics still had plenty of advocates in the decades that followed. Julian Huxley, for example, presided over the British Eugenics Society from 1959 to 1962, while also promoting the transhumanist idea that by controlling “the mechanisms of heredity” and using “a method of genetic change” (i.e., eugenics), “the human species can, if it wishes, transcend itself — not just sporadically, an individual here in one way, an individual there in another way, but in its entirety, as humanity.”

Today, a number of philosophers have defended what’s called “liberal eugenics” — transhumanism being an example — which many contrast with the “old” or “authoritarian” eugenics of the past century, although we will see in my second article for The Dig that the “old” and “new” eugenics are really not so different in practice.

Effective Altruism (EA)

To understand the idea of “effective altruism,” it helps to break the term down. First, the “altruism” part can be traced back, most notably, to a 1972 article by Peter Singer, one of the leading effective altruists, titled “Famine, Affluence, and Morality.” It contains the famous “drowning child” scenario, in which you see a child struggling to stay afloat in a nearby pond. Most of us wouldn’t hesitate to, say, ruin a nice new pair of shoes to save the child. But what’s the difference, really, between a child drowning 30 feet away from us and a child starving to death on the other side of the world? What does physical proximity have to do with morality? Maybe what those of us in affluent countries should do is forgo purchasing those new shoes in the first place (assuming that our old shoes are still wearable) and instead give that money to help disadvantaged people suffering from poverty or a devastating famine. This is the altruism part: selflessly promoting the well-being of others for their own sakes.

But there’s a follow-up question: If you’re convinced by Singer’s argument that we should be altruistic and give some fraction of our disposable income to people in need, who exactly should we give it to? Which charities yield the biggest bang for one’s buck? What if charity X can save 100 lives with $10,000, while charity Y would only save a single life? Obviously, you’d want to give your money to the first charity. But how would you know that one charity is so much better than the other?

MacAskill has argued that we should actively support sweatshops, ignore “Fairtrade” goods, and resist giving to disaster relief.

This is where the “effective” part enters the picture: In the 2000s, a small group of people, including William MacAskill and Toby Ord, began to seriously investigate these questions. Their aim was to use “reason and evidence” to determine which charities are the most effective at improving the world, for the sake of — in MacAskill’s words — “doing good better.” That’s how the effective altruism movement came about, with the term itself being independently coined in 2007 and 2011.

At first glance, all of this sounds pretty good, right? However, some of the conclusions that effective altruists ended up with are controversial and highly counterintuitive. For example, MacAskill has argued that we should actively support sweatshops, ignore “Fairtrade” goods and resist giving to disaster relief. He’s also defended an idea called “earn to give.” Let’s say that you want to save as many lives as possible with your money. One of the best ways to do this, according to effective altruists, is by donating to the Against Malaria Foundation, which distributes bed nets that help prevent mosquito bites. So, the more money you give the Against Malaria Foundation, the more bed nets get distributed and the more lives you save.

This led MacAskill to argue that some people should pursue the most lucrative careers possible, even if this means working for what he calls “evil organizations,” like petrochemical companies or companies on Wall Street. In fact, in 2012 MacAskill traveled to the United States and happened to sit down for lunch with a young MIT student named Sam Bankman-Fried, and convinced him to pursue this “earn to give” path. Bankman-Fried then got a job at a proprietary trading firm called Jane Street Capital, where other effective altruists have worked, and later decided to get into crypto to — as one journalist put it — “get filthy rich, for charity’s sake.” Consequently, Bankman-Fried founded two companies called Alameda Research and FTX, the latter of which catastrophically imploded last November. Bankman-Fried is now facing charges of “fraud, conspiracy to commit money laundering and conspiracy to defraud the U.S. and violate campaign finance laws,” which carry a maximum sentence of 115 years.

Longtermism

Finally, let’s talk about longtermism. This ideology has been the primary focus of my critiques over the past two years, as I am genuinely worried that it could have extremely dangerous consequences if those in power were to take it seriously. One way to understand its development goes like this: In the early 2000s, Nick Bostrom published a number of articles on something he called “existential risks.” In one of these articles, he pointed out that if humanity were to colonize an agglomeration of galaxies called the Virgo Supercluster, which includes our own Milky Way, the future human population could be enormous. Not only could our descendants live on exoplanets similar to the fourth rock from the sun that we call home (i.e., Earth), but we could gather material resources and build planet-sized computers on which to run virtual-reality worlds full of trillions and trillions of people.

In total, he estimated that some 10^38 people — that’s a 1 followed by 38 zeros — could exist in the Virgo Supercluster per century if we create these giant computer simulations, although he later crunched the numbers and estimated some 10^58 simulated people within the entire universe. That’s a really, really big number. So far on Earth, there have been about 117 billion humans, which is 117 followed by “only” nine zeros. The future population could absolutely dwarf the total number of people who’ve so far existed. Although our past is pretty “big,” the future could be so much bigger.

Sometime around the end of the 2000s, it seems that some effective altruists came across Bostrom’s work and were struck by an epiphany: If the aim is to positively influence the greatest number of people possible, and if most people who could ever exist would exist in the far future, then maybe what we should do is focus on them rather than current-day people. Even if there’s a tiny chance of influencing these far-future folks living in huge computer simulations, the fact that there are so many still yields the conclusion that they should be our main concern.

As MacAskill and a colleague wrote in 2019, longtermism implies that we can more or less simply ignore the effects of our actions over the next 100 or even 1,000 years, focusing instead on their consequences beyond this “near-termist” horizon.

As MacAskill and a colleague wrote in 2019, longtermism implies that we can more or less simply ignore the effects of our actions over the next 100 or even 1,000 years, focusing instead on their consequences beyond this “near-termist” horizon. It’s not that contemporary people and problems don’t matter, it’s just that, by virtue of its potential bigness, the far future is much more important. In a phrase: Won’t someone consider the vast multitude of unborn (digital) people?

Longtermism was born in a collision between the EA idea of “doing the most good possible” and the realization that the future population over the next “millions, billions and trillions of years” could be much bigger than the current population, or even the total number of people who’ve so far journeyed from the cradle to the grave on this twirling planetary spaceship of ours.

This being said, it is useful to distinguish between two versions of longtermism: the moderate version says that focusing on the far future is a key moral priority of our time whereas the radical version says that this is the key priority — nothing matters more. In his recent book “What We Owe the Future,” MacAskill defends the moderate version, although as I’ve argued elsewhere, he probably did this for marketing reasons, since the moderate version is less off-putting than the radical one. However, the radical version is what one finds defended in many of longtermism’s founding documents, and MacAskill himself told a Vox reporter last year that he’s “sympathetic” with radical longtermism and thinks it’s “probably right” (to quote the reporter).

This is the lay of the land — the main characters, the central ideas, that populated my last Truthdig article. I hope this helps readers understand what I believe is the significant overlap between longtermism and the racist, xenophobic, ableist and classist attitudes that animated 20th-century eugenicists.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.