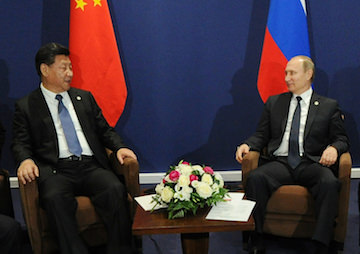

Live Blog: Is the Emerging China-Russia Axis Shifting the World’s Balance of Power?

A Brookings Institution panel explores whether closer alignment between Russia and China is changing international politics "to the disadvantage" of U.S., Europe and the rest of Asia.

As Russia and China became closer over the past decade, both countries took steps to alter the status quo in their respective spheres of influence. A Brookings Institution panel explores whether the closer alignment is changing international politics “to the disadvantage,” as Brookings puts it, of U.S., Europe and the rest of Asia.

Brookings brings together experts from Japan and the United States to examine how recent actions by China and Russia have shifted the global order, with special attention to the question of “whether new geopolitical rivalries have returned both between and within the East and the West.”

The event will close with an audience Q-and-A. Truthdig will follow along here.

Editor Alexander Kelly’s takeaway:

The second part of the title that the Brookings Institution gave to this talk, “The Return of Geopolitics?”, suggests the view that certain mindless forces that once drove international relations recently gave way to a system of rules (as panelist Thomas Wright put it) that facilitate open negotiation among more or less equal partners.

These rules may appear fair to those of us whose sympathies lie with the putatively liberal and democratic Western powers that prevailed in the struggles of the 20th century. But to people whose allegiances and sense of trust point elsewhere, they remain rules written by others. And to put it mildly, they aren’t necessarily just.

This fact is omitted too often in expert discussion about the behavior of officials leading this or that nation, especially when audiences are asked to pass judgment. If the panelists recognize it, they could have made it clearer in their presentations.

Moderator Richard C. Bush III concludes the talk, thanking the panelists and the audience.

10:55 a.m. ET: What of China-Russia relations in the Middle East? Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Community Party of China, offered to bring the Silk Road into the Middle East to create peace by creating jobs. Wright’s answer: China respects America’s role in the Middle East. What we’re really discussing is ways in which Chinese influence may be exercised in East Asia that could be destabilizing over a five- or 10-year period.

10:54 a.m. ET: How would Hillary Clinton change what was discussed? Panelist David Gordon: “Clinton would probably move to engage personally more decisively with U.S. allies in the region while also trying to sustain engagement with China. So she would … follow a track not [at] all dissimilar to the current thrust of U.S. policy but much more hands-on.” Donald Trump? You’d “see a lot of aggressive and assertive commercial economic and financial diplomacy vis-à-vis China, but actually, Trump, unless overturned by others, his orientation would be to not be nearly as engaged as a security balancer in the Western Pacific.”

10:50 a.m. ET: Is Russia “over,” and is China the future? It depends on where you sit, Wright says. Russian President Vladimir Putin is likely to be in power until at least 2024, with a different idea of international order than the U.S. and its allies, and with a capacity to “create mischief,” he says, apparently sincerely.

10:44 a.m. ET: Request from a former U.S. intelligence associate: Discuss the Chinese relations with Mongolia. Panelist Chisako Masuo says that economically, China wants to enlarge its sphere of influence in Mongolia but Mongolia has been cautious about accepting China’s enlarged role.

10:39 a.m. ET: China is not focused on oil extraction from shale, Gordon says, and China has intense interest in gaining access to the North American energy market. The U.S. can use this as “a leverage point.”

10:29 a.m. ET: The international community is well represented at this panel. Accents make some questioners and speakers difficult for this reporter to understand.

10:26 a.m. ET: The Q-and-A begins.

10:25 a.m. ET: Masuo suggests that the U.S. make China a greater foreign policy priority than Russia.

10:19 a.m. ET: After reviewing at length the evolution of China’s borders and the historical circumstances shaping its ability to expand, Masuo confirms that Russia’s best friend at the moment is China. But Russia has approached India to “hedge against China.”

10:07 a.m. ET: Masuo says she is chiefly focused on China’s relationship with other Asian partners and on observing how China’s partners observe and regard its rise. The driving force behind the return of geopolitics in the region is the rise of China, she argues, and this—not Islamic extremism—is the “preeminent geopolitical challenge.” In her eyes, “the Russia-China marriage is a marriage of convenience.”

10:02 a.m. ET: The interests of China and Russia diverge, Gordon adds, as China seeks to grow its economic influence and Russia is not brought along as an equal actor. The core of Russian influence remains its ability to use military power, as in Crimea and Syria. And that’s less effective. China, on the other hand, is able to throw its weight around economically.

The partnership is real, as is the interest in establishing regional strengths, Gordon says. But at the same time, the big driver that brought Russia and China together was the enticement of the China-Russia energy partnership, and market conditions are making those dynamics “much less real.” Energy dynamics over time are likely to make Russia structurally a more challenging actor internationally, but the same isn’t necessarily true of China.

9:55 a.m. ET: Gordon acknowledges anxiety among Western analysts over the emerging Russian-China alliance. He urges a nuanced view of the relations strongly influenced by energy, where cooperation between Russia and China “has already begun to founder.” Russia expected benefits that it has not received from China, including help building an energy pipeline. The Chinese haven’t helped Russians finance this pipeline and have not “made big investments that Russia expects” in oil fields.

“Russia is increasingly wary of becoming a resource appendage to China,” Gordon says. Russia is “coming to terms” with its “limited energy choices.” The shift to China was not just about geopolitical relations with the U.S.; it was also heavily about Russia’s relations with Europe, and this quest for leverage through options. And “that hedge has not worked out very well” and now we’re seeing a shift back by Russia toward Europe.

9:48 a.m ET: Russia responded to these events by seeking to enhance Russian-Chinese energy and economic ties, Gordon says. Russia and China subsequently held joint military exercises.

9:45 a.m. ET: Gordon says the key driver in the move to closer Russia-China relations was the Russian invasion of Crimea during the recent Ukraine crisis, the Western imposition of sanctions and the drop of oil prices, upon which Russia’s economy depends. Ukraine was the “test case” for the so-called rules-based Western view of international relations, with the West testing out the efficacy of financial pressures on getting Russia to do what it wants.

9:36 a.m. ET: How should the U.S. and Japan respond to the “new geopolitics”? Accept and resolve to manage the “quasi-alliance” between Russia and China, divide the theater into “Pacific Russia” and “European Russia,” free Japan to work beyond its home region, etc.

9:36 a.m. ET: Japanese scholar and panelist Akihito Iwashita states that perceptions among Chinese that Russians are enemies have dropped in recent years.

9:31 a.m. ET: With its many borders, Iwashita suggests that we think of Russia’s perspective as shaped by a sort of “border paranoia.”

9:29 a.m. ET: Iwashita separates the regions of power into northern, middle and southern tiers.

9:26 a.m. ET: Iwashita notes that far more people are concerned with the relations being discussed than were a few years ago. What changed? Most people are frustrated with Russian revisionism, he suggests.

9:24 a.m. ET: Wright suggests an overall challenge: How do we preserve a rules-based international order, rather than an order maintained by the force of regional power? A respect for law on the part of all governments is key to that.

9:22 a.m. ET: But Russia and China have a shared interest in blunting the expansion of U.S. power.

9:21 a.m. ET: Russia has two objectives, Wright says: to weaken the EU security order and to increase power at its borders, while China acknowledges that regional power is shared, for the time being at least, with the United States. Chinese strategy is predicated on there not being a conflict, on there being an absence of war. China wants to take incremental steps to reshape the regional order to their advantage. Both Russian and Chinese visions are revisionist in their long-term objectives and are concerned with increasing regional power.

9:18 a.m. ET: Why does this matter? “I think the international order rests on healthy regional orders,” Wright says. It’s more important that Europe is at peace than that there be an agreement with the International Monetary Fund. The basis of healthy global order is healthy regional order, he says.

Russia is a power in long-term decline, he adds. It doesn’t build or make a lot of things and sees the EU as the super power.

9:12 a.m. ET: Heads of state including George Bush and Barack Obama have urged international cooperation on terrorism and foreign policy respectively, Wright says. There’s no “objective” way in which the threat to Russia has increased, he says. But Putin saw encroachments by the West toward Russia as a threat to Russia nonetheless.

9:12 a.m. ET: Panelist Thomas Wright says there’s nothing like an early morning discussion on China and Russia to get one channeling one’s “inner Henry Kissinger.” He frames the discussion in terms of whether or not countries may wish to see each other weakened or strengthened. U.S. strategy at the turn of the century, he suggests, was that all countries were riding on the same road forward.

9:06 a.m. ET: Moderator Richard C. Bush III, director of the Center for East Asia Policy Studies, introduces panelists Akihito Iwashita, professor at the Slavic-Eurasian Research Center at Hokkaido University and the Center for Asia-Pacific Future Studies at Kyushu University; Chisako Masuo, associate professor at the Graduate School of Social and Cultural Studies at Kyushu University; Thomas Wright, director of the Project on International Order and Strategy and fellow in foreign policy at the Center on the United States and Europe at the Project on International Order and Strategy; and David Gordon, senior advisor and former chairman of the Eurasia Group.

Bush says the question mark at the end of the panel’s title is the most important part, while the second most important part is the word “geopolitics,” which denotes the idea that geography matters in international relations, with common borders acting as sites of struggle or benefit.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.