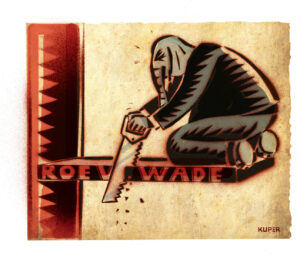

Life, Death and Politics

Make no mistake, the Supreme Court's recent abortion ruling stands between a woman, her doctor and the choices that could save her life.WASHINGTON — The bleeding began just after Donna McNichol’s routine exam in the early weeks of her first pregnancy. “They told me I might spot a little bit after the exam,” she recalled in an interview. “But I wasn’t spotting. I was flowing.”

The pregnancy was planned and joyful. The young California health aide and her teacher husband had just announced it to their families with a celebratory video of themselves playing “Wheel of Fortune.” “I was really blessed,” McNichol, now 49, says.

Her bleeding continued even when she rested in bed. Then the nausea started. “They kept saying that was a good sign, but it wasn’t,” McNichol says. “Sometimes I would pass big blood clots — even the size of my fist.”

Neither her own doctors nor colleagues at the Planned Parenthood clinic where McNichol was working could diagnose what was wrong. She underwent test after test. No well-known aberration that can ruin a pregnancy was completely ruled out — or in. As the blood loss continued, McNichol took a reading of her iron count and discovered it was dangerously low. Fatigue sapped her. “I was just getting sicker because I was losing so much blood,” she says.

New worries arose. She wanted badly to continue the pregnancy, but it was clear that she’d eventually need blood transfusions — and acquired immune deficiency syndrome was just emerging as a little-understood menace in the San Francisco Bay area, where McNichol lives. “The blood supply wasn’t screened,” she recalls.

Though her health and her concern about it worsened by the day, she still hoped to continue the pregnancy. But eventually, she began asking her closest relatives and friends what to do. “The worst part of it was that it was never clear,” McNichol says. “I never knew what was the right thing to do.”

At 20 weeks, McNichol had an abortion using a procedure she says fit the description of the intact extraction method that the U.S. Supreme Court banned last week. Afterward, she learned her condition was placental abruption — the placenta, which nourishes the fetus, was breaking up and sloughing off from her uterus. The condition can cause a woman to bleed to death. “It’s one of the causes of maternal death,” McNichol says.

McNichol went on to have two healthy pregnancies. Her children are now teenagers. She first told her story in a friend-of-court brief submitted to the lower courts as the landmark abortion case wound its way upward.

It seems that neither she nor her doctors are callous baby killers who will use any and all means to destroy a fetus they’ve decided to cavalierly discard. And nothing about McNichol’s case supports Justice Anthony Kennedy’s conclusion that Congress is correct to ban an abortion method because “some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained. … Severe depression and loss of esteem can follow.” Yet Kennedy wrote that he found “no reliable data” to support this conclusion.

McNichol told me that once she learned that her life had been at risk, the moral qualms that weighed so heavily upon her before choosing to terminate the pregnancy lifted.

The anti-abortion movement has fooled the country into believing that all the Supreme Court did last week was ban a particularly odious and medically unwarranted method of abortion. That is the least of it. The court emphatically said that Congress — not doctors or patients — can decide what’s best for women’s health. The high court ruled that when there is “medical uncertainty,” lawmakers can decide what course of treatment is, or isn’t, legal.

We are all Terri Schiavo now. We all can be subject to second-guessing of our family’s medical choices from the halls of Congress.

McNichol’s doctors couldn’t diagnose what was wrong. How could the justices? How could 535 members of the House and Senate — 448 of them men — prescribe the best medicine for a woman they’ve never met, let alone examined with a trained eye?

“I have to tell you, I asked everyone — what should I do?” McNichol says. “I never thought about calling up my representative in Congress to ask them what to do. There was no way that someone who has any other agenda but my well-being could make that decision. It wasn’t a political decision. It was a medical, personal decision.”

It is the sort of decision American women no longer can assume they are free to make.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at symbol)washpost.com.

(c) 2007, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.