Let’s Get Out of the 2002 Trap

Primary voters and pundits should stop browbeating Clinton over her Iraq war vote and instead take a hard look at her and the other candidates' plans for Iraq.WASHINGTON — Never underestimate the capacity of primary voters to dance on the head of a pin.

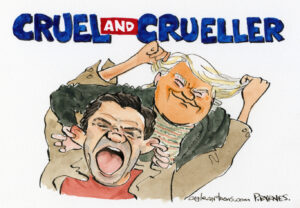

It is a lesson we learn every four years and yet are doomed to relive during the interminable grope toward the eventual presidential nominees. At some point, Republicans will no doubt skirmish over their candidates’ purity on tax cuts or abortion or gays. But at the moment, the phenomenon is best seen in the excruciating counterplay between Democratic antiwar activists and Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Clinton has refused the activists’ many invitations to apologize for her 2002 vote authorizing the Iraq war — or at least admit to an error of judgment. After this unpleasant joust had gone on for at least one town hall meeting too many, Clinton finally said that if an apology, or lack thereof, were the single most important issue in making their choice, then voters could simply pick another candidate.

Whether voters will take this as an example of admirable resolve or stunning arrogance is a question only they can answer. But before they do, a few other questions deserve a thorough mulling.

What changes in today’s Iraq when Clinton or any other presidential candidate, Democrat or Republican, renounces that 2002 vote? What exactly would have changed if Senate Democrats had risen up together and voted against the Iraq resolution in the first place?

Nothing. George W. Bush was determined to invade Iraq, topple Saddam Hussein and begin his frighteningly ill-advised project to remake the Middle East in some neoconservative image no matter what any expert or political institution, at home or abroad, had to say about it.

Among those the president brushed aside were top military commanders, plus Secretary of State Colin Powell and just about the entire State Department. Bush shunned the advice of European allies and friendly Arab states, almost all of whom warned against the adventure. He disregarded the United Nations Security Council, which refused to give its imprimatur to the military action, despite months of White House effort at winning an endorsement.

A majority of House Democrats voted against the 2002 war resolution. They were resolutely ignored.

Even if every Democratic candidate who was then in the Senate and now is running for president — Clinton, John Edwards, Joe Biden and Chris Dodd — had voted against the resolution, it would have passed overwhelmingly. And even if every single Senate Democrat, along with Rhode Island’s now-defeated Republican moderate Lincoln Chafee, had stood against the war, it would have been waged anyway. White House lawyers already had made clear their view that the president didn’t need congressional authorization to invade Iraq. Bush sought a vote only after public urging from senior lawmakers, Republicans notably among them.

And by the way, the same Democratic primary voters who now seek to refight the battle of 2002 already have been offered a potential presidential nominee who did not cast a congressional vote for the Iraq war and who opposed it — early, often and loudly. His name is Howard Dean. In 2004, he lost both Iowa and New Hampshire to war supporter John Kerry.

The agony of Iraq has grown deeper since then. It sheds an even harsher light on the poisonous combination of political expediency and war hysteria that seized Capitol Hill more than four years ago. In that noxious atmosphere, those lawmakers who voted “no” were correct and courageous. But other than Dennis Kucinich, none is running for president.

Bush is determined to prolong the Iraq folly despite the voters’ will to end it. Hard-nosed manipulation by the White House and Senate Republicans has prevented even a symbolic vote against Bush’s troop escalation — and this with Democrats in control of the chamber.

All of this is maddening. It is dangerous for democracy. It infuriates everyone, myself included, who objected to this war before it began.

But is this fury best expressed in public bloodletting over who is, or isn’t, sufficiently contrite? Or is it better directed at questioning candidates about their plans for getting us out of Iraq and restoring American respect abroad?

Democrats should force Biden to defend his plan for partitioning Iraq and press Clinton to better explain her ideas for capping the number of troops and redeploying them. They must make Barack Obama say just how he expects events to unfold in the Middle East if U.S. combat forces are withdrawn from Iraq by March 2008, as he has proposed.

We could all learn something. And Democrats might even convince the country that theirs is the party of solutions, not sour grapes.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at symbol)washpost.com.

© 2007, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.