Latest Readings

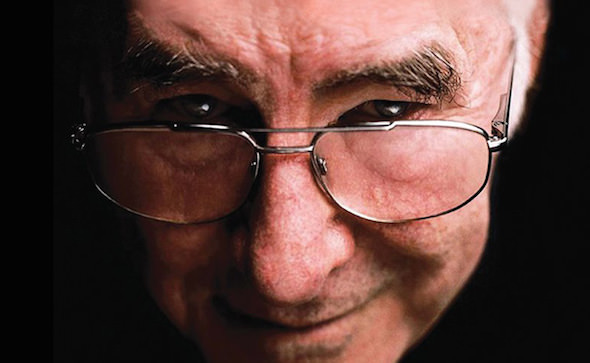

Clive James, the great cultural critic diagnosed with leukemia in 2010, revisits a lifetime of reading in his latest, and perhaps last book: “If you don’t know the exact moment when the lights will go out, you might as well read until they do.”

Yale University Press

|

To see long excerpts from “Latest Readings” at Google Books, click here. |

“Latest Readings” A book by Clive James

“As a journalist and critic,” Clive James wrote eight years ago in the introduction to his awe-inspiring, encyclopedic “Cultural Amnesia,” “a premature post-modernist, I was often criticized in my turn about the construction of a poem and of a grand prix racing car in the same breath. … It was a sore point, and often a sore point reveals where the real point is. Humanism wasn’t in the separate activities: humanism was the connection between them. Humanism was a particularized but unconfined concern with all the high-quality products of the creative impulse, which could be distinguished from the destructive one by its propensity to increase the variety of the created world rather than reduce it.”

There is an anthem of sorts tucked in that amazing paragraph. My subject is James’ new book, “Latest Readings,” which may be his last as his health has been failing since being diagnosed with leukemia in 2010, but I go back to his definitive work, “Cultural Amnesia,” a compendium of the most important artistic, philosophical and political figures of the 20th century, to put his career and achievement in perspective. Lucidity has always been a hallmark of James’ prose; if his meaning isn’t always easy to grasp, it’s only because his critical sensibilities cast so wide a net that every observation he makes offers so much to digest.

For years now, many have seen James as the successor to Edmund Wilson — the greatest critic in the English language. For the most part, this is fair. Like Wilson, James is one of the last critics to believe the world can actually be understood by an individual. James, however, is as profound as Wilson while being far more Catholic. Wilson is largely remembered today as the great critic of the radical age of the 20th century novel — subsequent generations of American readers weren’t to think of Joyce or Faulkner without first going through Wilson — but I would insist that James’ taste in literature is far more encompassing.

Wilson could never dig Kafka and harbored a positive dislike of Spanish literature. It’s depressing to think that had he lived longer he would surely have shut out the exotic breezes wafting into the Northern Hemisphere from Jorge Luis Borges’ pampas and Gabriel García Márquez’s Macondo. James, on the other hand, seems to have absorbed Latin American letters and is one of the first critics to give Mario Vargas Llosa significance as a cultural figure.

Wilson had no feel for popular culture. Despite his reputation as a progressive, he strikes the modern reader as more British in his outlook than the Australian-born James. Wilson had no tolerance for genre fiction, movies or jazz despite, according to his last and best biographer, Lewis Dabney, a penchant for Frank Sinatra records.

The last, I suppose, comes under the heading of guilty pleasure. To Clive James, no pleasure is guilty. He has mined critical gold from sources Edmund Wilson would have shuddered at — Raymond Chandler, W.C. Fields, Louis Armstrong, or a rerun of “The Rockford Files.” And James has been, for more than 30 years, our greatest critic of poetry.

There are several hints in “Latest Readings” that James will leave us one last volume, on poetry. Meanwhile, if it turns out that “Latest Readings” is not the last reading, it is at the very least a book about choosing the last things to read.

“When I emerged from hospital in early 2010,” he writes, “with a certificate to say that I had a case of leukemia to go with my wrecked lungs, I could hear the clock ticking and I wondered whether it was worth reading anything both new and substantial or even rereading something substantial that I already knew about. … Even the slightest book of prose looked like a big thing that I might not have time to get through.”

As it turned out, rereading for James was not laborious — in fact, it actually made life worth living. After all, “the childish urge to understand everything doesn’t necessarily fade when the time approaches for you to do the most adult thing of all: vanish.”

Did our greatest living critic come to appreciate certain authors more because he was dying? It was “a revelation, after more than 50 years, to rediscover Joseph Conrad.”

“On the strength of this long-delayed second reading [of ‘Lord Jim’],” James writes, “the book struck me as no more exciting than it had once seemed, but a lot more interesting. I had long known Conrad to be a great writer: on the strength of ‘Under Western Eyes’ alone, he would have to be ranked high.” The novel, published in 1911, presages, in James’ view, the logical end of radicalism, i.e., terrorism. “ ‘Under Western Eyes’ is valuable not because it came true but because it rang true even at the time, only now we can better hear the deep, sad note.”

Of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises,” he is a bit more skeptical: “Hemingway’s little novel, which is really only an extended novella, was a thing of its time. Whether it is also a thing for eternity is debatable. Certainly it continues to count in my own eternity, but that will soon come to an end.”

There are writers who only now, near the end, he comes to appreciate, such as Kipling, whose faults he still acknowledges — “And yet, how brilliant.” There are writers he never thought he’d have time for — his daughter offered him Patrick O’Brian’s “Master and Commander.” “She was like a drug dealer handing out a free sample.” James ended up reading all 20 volumes, and “Jack Aubrey’s physical appearance never shifted. To my mind, he looked exactly like Russell Crowe.”

There are writers he tried again and found wanting. On Lawrence Durrell’s “Alexandria Quartet,” “Really it should have been judged as a mass of purple patches even then. Now it reads like a whole platter of overripe fruit.”

Some minor writers are given their due, including English comic novelist Osbert Lancaster, who chronicled the last days of a decaying English aristocracy. Should James even bother reading about a society he experienced only secondhand? “As I read, I can feel it all slipping away into time as I am myself. Probably all this stuff — this last stretch of a privileged social history — will never again come back into favor. … I ought to disapprove, but I can’t leave [Osbert’s books] alone.”

And there are writers whom he knows he will never get around to rereading, whose books are kept around for other purposes. Churchill’s six volumes on the history of World War II “are still there, as if I will have time to pay them another visit. But I probably won’t, so their presence is really talismanic.” There is also time for gobbling up a few inconsequential but tasty books about movies (“They are popcorn reading for people who are glad not to share their popcorn”), on movie critics (“One concludes that in the field of movie criticism there is a sucker born every minute”) and to dump a last bucket of vitriol on what used to be called the “new” criticism (“How did literary theory get started? Because the theorists couldn’t write.”).

Staring into the abyss, James even finds time to pen a superb closing line: “If I ever had a plaque, I would like it to say: He loved the written word, and he told the young.” To which I would add a few other words, from “Latest Readings:” “If you don’t know the exact moment when the lights will go out, you might as well read until they do.”

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.