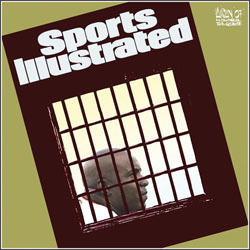

Lance Williams on Barry Bonds

The "Game of Shadows" co-author shares his thoughts on Barry Bonds' legal woes, the impact of steroids on sports and how Nancy Pelosi helped to keep him (Williams) out of jail.

The “Game of Shadows” co-author shares his thoughts on Barry Bonds’ legal woes, the impact of steroids on sports and how Nancy Pelosi helped to keep him (Williams) out of jail.

Listen to this interview.

Transcript:

James Harris:

Extra, extra! Read all about it! Baseball’s home run king was charged last week [Nov. 15] with obstruction of justice and perjury. He will stand trial Dec. 7, 2007. This is Truthdig. James Harris with Lance Williams, San Francisco Chronicle writer and co-author of “Game of Shadows: Barry Bonds, BALCO, and the Steroids Scandal That Rocked Professional Sports,” and that book title is secret coding for “I broke the Barry Bonds story.” Lance, how are you doing today?

Lance Williams: Happy to be here.

Harris: Well, Lance, I know you’ve been over there waiting to exhale. You yourself faced jail time for not responding to a subpoena that called for you to “out” your source, the source that gave you the information that led to the indictment of Barry Bonds. And since we’re not having this conversation through glass, I assume the government backed off. Why did they back off, and why aren’t you in jail?

Williams: The government says that it did an independent investigation and independently identified the person who leaked the information. We’ve never been able to [unintelligible] on them, whether they got the right guy, whether this guy or that guy was the source. The somewhat longer version is that Congress has changed hands and Attorney General [Alberto] Gonzales started getting letters from members of both the Republican and Democratic leadership in Congress saying, “Why are you going after these guys in a story about baseball?” And I really feel that after he got the letter from the new speaker of the House, he rethought the thing and decided to do an independent investigation. That’s my opinion.

Harris: So that was Nancy Pelosi that wrote that letter?

Williams: Yeah. We went back. Mark [reporter Mark Fainaru-Wada, co-author of the book] and I went back three times to Washington to lobby on behalf of a shield law for whistle-blowers and journalists to keep the federal government from trying to drag reporters and their sources before grand juries because it’s really bad for the country to do that. We’re going to lose independent sources of information about what our government is doing if they’re allowed to do that. And it was in that context that we met — oh, golly, everybody we met from Mike Pence [House member, R-Ind.] on the right to the new speaker and the new chair of the House Judiciary, Congressman Conyers [John Conyers, D-Mich.] and we got nine or 10 letters out of that on our behalf as well as support for the shield law. And I do feel — I don’t mean to be a reductionist here — but I really do feel that the government’s interest in resolving the case without throwing us in prison amped way up after they found out that prominent lawmakers thought that what the Justice Department was doing was nuts.

Harris: Do you feel at all like you prevented justice from being served by not outing your source?

Williams: I don’t think so. I think maybe a source of ours violated a court order, but I don’t think there’s any law about writing a true story in the newspaper. Perhaps Attorney General Gonzales would’ve liked to have had such a law on the books.

Harris: So there is no law prohibiting a reporter from publishing leaked testimony. …

Williams: No.

Harris: … or any type of testimony.

Williams: No, that’s not our system. You can come after reporters and so forth and you can come after the press, but you can’t restrain it, and you can’t criminalize it. That’s just not consistent with the First Amendment which our founders gave us.

Harris: I agree. You guys have avoided jail, and now Bonds seems to be the guy again.

Williams: Now it’s somebody else’s turn in the barrel. My heart goes out to anybody who has the federal government with their gun sights on you. So it’s a tough time for the home run king now.

Harris: But do you really feel bad for the home run king? He has not been a friend to the media. Not at all.

Williams: I feel bad for anybody who’s in that predicament of being under indictment or scrutiny of the federal government, just because it’s very intense. It’s a human reaction on my part. Bonds could’ve avoided all of this trouble if he had testified truthfully in front of the grand jury that was investigating the BALCO case. Most of the athletes who went in there — and there were more than 30 of them — went in and admitted what they were doing and if you admitted it, you didn’t get into any trouble. They were given immunity from prosecution because the government hoped to use them in trial as witnesses against the dope dealers, who ultimately pleaded guilty, so there was no trial. But that was the dynamic there. Bonds — and it’s understandable because it’s embarrassing — didn’t want to admit that he had used banned drugs. But now my advice, for anybody if you’re ever faced with being questioned by the federal law enforcement: either don’t talk to them, or tell them the truth, because the third alternative is really bad. They get mad when you don’t tell them the truth, and here we go: This is the fourth athlete in the BALCO case to be brought up on charges of lying about their drug use.

Harris: Now who are the others?

Williams: Sure. The most prominent is Marion Jones, the star of the Sydney Olympics. Five medals there in 2000. She pleaded guilty last month to lying to a BALCO investigator about her use of banned drugs. Then there’s an elite track coach, Trevor Graham, and a bicycle racer called Tammy Thomas. Both are accused, also, of lying to the feds, either the grand jury or the investigators, in this big investigation into the use of performance-enhancing drugs.Harris: So you’re talking about Marion Jones, Trevor Graham, Tammy Thomas and Barry Bonds. Is that it?

Williams: Plus athletes who were subpoenaed before the grand jury or who were interviewed by federal agents. Most of them told the truth and they’ve gone on with their lives, one way or the other.

Harris: So they only have gone after the four. I find that problematic, though, Lance, that other people were doing this, that they were using steroids, but because these four lied, they seem to be facing a higher consequence.

Williams: I don’t understand how the federal government prosecuted this case from the get-go. To me the whole drug conspiracy at BALCO really was for the benefit of the millionaire athletes to immunize them from prosecution and to actually protect their “privacy.” The government sealed all the files regarding the drug use by most of the athletes. I just didn’t understand why they were doing it the way they were doing it. But then I didn’t understand why they were so hot to put me in prison, either.

Harris: This has been a mess. They appoint [former Sen.] George Mitchell the private prosecutor to handle this case. What has been your opinion on the way that Bud Selig, the commissioner of baseball, has handled this steroids investigation?

Williams: Commissioner Selig is constrained by the competing forces in baseball. The union is strong, the owners are powerful and willful, and he doesn’t have a free hand. Having said that, though, he’s also an extremely reactive guy. He’s never really tried to get out in front of this problem, which has been building for years. The current strategy, which actually was developed after our book came out, was to hire a former U.S. senator, George Mitchell, to do an investigation of steroid use in the sport. Now that’s been going on since March of 2006. Some sort of report is supposed to be released later this year. And the real interesting thing is what baseball will do with the information, assuming it’s a credible report. If it is, there’s going to be lots of athletes named in it, lots of ballplayers named in it, and it really could shake the game up. And I just don’t know what they’re going to do as a follow-up.

Harris: Has there been a scandal in baseball of this magnitude since the Black Sox scandal in the early 20th century?

Williams: I don’t think so. There’ve been incidents that were troubling, but I think if Mitchell does a good report, you’re going to find out that lots and lots of players for a period of 10 years were using performance-enhancing drugs, that the game was all distorted as a result, the players exposing themselves to major health risks in an effort to get these big contracts and hit the long ball and so forth, and the game’s leadership turning a blind eye to it. It’s not a pretty picture. It seems to me that they need to get a handle on the problem to restore the game. You don’t want it to go the way of wrestling where in 20 years they’ll have a fan base who’s still interested in baseball and the rest will be saying, “Why do you care about that? Everyone knows it’s crooked.”

Harris: Exactly. You make the wrestling comparison. And there were drugs involved there in the middle ’80s and the …

Williams: Yeah, sure.

Harris: … has come under fire for that as well. Lance, let me play devil’s advocate here, because a few columns around the country take you to task and they say, “You know what? You have uncovered business that should not be uncovered. Everybody — from Mark McGwire to Sammy Sosa, to … you pick a guy that we all love — was probably doping.” What do you say to those people that say that you ruined baseball?

Williams: I think baseball runs the risk of ruining itself by allowing the use of illegal, powerful, harmful drugs and really forcing these young athletes to use them if they want to make the team. It’s just not a good situation. It’s not the sport that’s being presented to the fans. Baseball says it’s a clean game. Well, it needs to clean itself up, and I think the stories, to the extent that they are an agent for making that happen, I’m happy to be a part of it. Lots of fans are uncomfortable with the idea of the home run record being held by a guy who’s using banned drugs, and they’re going to be uncomfortable with the results of the Mitchell report, too. And I think that discomfort reflects what the fans really want. They might want to see the long ball and might they want to see the record-breaking performances, but they want to believe that they’re being done on the natural. Baseball has that obligation to try to make that happen if it can.Harris: But what about McGwire? He didn’t lie at that testimony, and you watched it, probably as I did, and he said, “You know what, I don’t want to talk about the past,” so he never faced those demons.

Williams: The difference between McGwire and Bonds is that McGwire was fortunate enough not to be obtaining drugs from an outfit that was under federal law enforcement scrutiny. That’s the whole difference. Bonds happened to be, through his own misfortune, a client at BALCO, which the government had targeted as a steroid mill. McGwire — there’s no other inference one could draw from that testimony before Congress then that Mac was a juicer. That’s what Jose Canseco said, and Jose was sitting — what? — 10 feet from him?

Harris: Exactly.

Williams: Mac could’ve said, “You know, this is a lie. I didn’t do it,” and instead he said, “I don’t want to talk about the past.” You saw the truth about Mark’s career revealed in those remarks. The reluctance to deny it spoke volumes.

Harris: But what was it about BALCO? Was it the type of drug? Was it the secrecy? What made the government so hot for these guys?

Williams: I think what got them cranked up was the knowledge that an undetectable steroid was being distributed there. The original focus of BALCO was track and field, and there was a track meet at Stanford University in the summer of 2003. “The Nationals,” they’re called. The head man at BALCO, Victor Conte, was using … was distributing — and fairly well-known among other competitors — was distributing this stuff called “The Clear,” which was a steroid but it was one that, because it had been tweaked in terms of its molecular structure, the testers couldn’t find it when they ran the urine and blood of the athletes, and so it was like a complete free pass to juice. And I think when the authorities learned that this was the dynamic of BALCO, that’s what got them cranked up.

Harris: I was in the car with my good buddy the other day, and he said this of Barry Bonds: Not only was he taking drugs — that was one thing, and I’d love to hear your response to his thought — but he was cheating, he sought out to hide the fact that he was taking drugs, then he went out publicly and lied about that fact, and then he was an asshole about it.

Williams: And I think that does describe the dynamic. I don’t know how this would’ve played out if Bonds were a warm and lovable athletic hero. Maybe it would’ve played out slightly differently, but, of course, he wouldn’t be the athlete he is. That whole prickly side of his personality and that arrogance and so forth — I think that’s part of what made him such a great competitor, so you can’t really separate it. Certainly, though, he wasn’t the only guy who used drugs. Unfortunately, he was one of a handful of ballplayers who were dragged in before a grand jury and asked about it. In my opinion he used poor judgment and didn’t ‘fess up and now has this big mess on his hands. There’s no guarantee that he’ll be convicted at a trial at all. This is San Francisco. He is the well-loved sports figure. At least in this town. But who wants to go through this mess?

Harris: It is a mess, and this is a federal case, is it not?

Williams: It is.

Harris: And their conviction rate is 90 percent?

Williams: Yeah. He might beat the case or fight it to a hung jury, but at the end of the day, you really get whupped on in that process, and I don’t think his reputation is going to emerge in any improved shape, even if he manages that. It’s just too darned bad. He could have, I think, headed this off, even after the grand jury testimony was transcribed. I think he could’ve had somebody call over there and say, “I want to amend my statement,” and they might have really let it go. But it’s fairly inflamed now; it’s to the point of an indictment. His trainer sat in prison for a year rather than testifying against him. It’s just gotten out of hand.

Harris: Do you think you can compare them? You can look at what Marion Jones did a couple of weeks ago and she came out crying and said, “You know what? I lied.” And we don’t seem to be talking about that as much. But I still wonder if they would’ve been that kind to Barry Bonds because of the type of person he was before any of these stories broke.

Williams: Mm-hmm. It’s unimaginable to me that Barry would go out there and humble himself the way Marion did.

Harris: Yeah.

Williams: That’s just not the way he’s wired, so if he would do something like that, it would be a way of turning the temperature down on this thing and maybe working it out, but it’s so hypothetical, because he’s really not that kind of guy.Harris: In your recent story about Barry Bonds there was a quote from Bonds, I think in 2003, and it says, “If I’m stronger, it doesn’t matter; I’ve still got to be able to hit the baseball.”

Williams: Mmm.

Harris: True?

Williams: Yeah, that’s true. The drugs don’t take an average person and make them into a superior athlete. What they do is take a really good athlete and make them better. If you can hit the ball with more power, hit it harder, it’s going to go farther. That stands to reason. But certainly he was a wonderful baseball player before he ever turned to the banned drugs. I can’t imagine he would still be playing today without the assistance of banned drugs. He’s 43 years old but had a really good career before he turned to that. The future is a process. If he decides to go to trial, we’ll have six to nine months of legal motions, perhaps an attempt to satisfy the indictment and then, if that fails, go to trial and, my goodness, that’ll be just a heck of a story. I can’t even imagine. You have the prospect of him having to take the witness stand. He doesn’t have the legal requirement to use it, but usually to beat a perjury case you have to put the guy on and he’s got to say, “Hey, I didn’t do it,” or “Here’s what I thought I was being asked,” or whatever. So it’ll just be fascinating.

Harris: We’ll all be watching. That may become the trial of the new century. But what you say about taking the stand, remember, O.J. [Simpson] never took the stand to say “I didn’t do it.”

Williams: Yeah, no. It’s true. He [Bonds] might be able to avoid it. It just depends on how the evidence rolls in. I don’t know these lawyers very well. I just think it’ll be fascinating to watch, and I’m just so happy it’s not about me now.

Harris: Me too. I don’t think journalists are fit for prison, Lance, so I’m glad, too. I’m glad it’s not you.

Williams: I don’t want to be sitting up there anymore.

Harris: A final thought. Let’s imagine a year into the future, let’s say Bonds is guilty. And I think it’s pretty clear — maybe some would say as clear as O.J.’s case was before that was decided. Let’s say that he’s guilty.

Williams: Mm-hmm.

Harris: Should baseball tear his records down or should they settle for an asterisk?

Williams: They’ve never done that, really. They’ve tried it with [Roger] Maris’ record for a few years and abandoned it. You can still look in the books and see the number of Shoeless Joe Jackson, who was involved in the Black Sox scandal, or Pete Rose, who was banned from the game for betting on it. Their numbers are still in the books. I just don’t think that’s where this is headed. It would be extraordinary if they did that. I think more likely where the judgment will be passed is going to be on whether he gets in the Hall of Fame or not. But I think his numbers will be in the book until somebody surpasses him. He’ll be the home run king until that day.

Harris: Final thought from me is, I think you’re right and I think that baseball is looking for something to blame their problems on and I think that they are losing a market share, not because of the steroids scandal and not because of the work that you guys did, but because people just aren’t interested in America’s game like they used to be.

Williams: It could be. It’s an acquired taste and many of us have acquired it. I think baseball still has quite a future if it can get a handle on this particular problem. If it can’t, forget it, but if it can wrap its arms around it and convince people that it’s serious about letting the athletes play drug-free, I think there’ll be a lot of people watching games.

Harris: Lance Williams, San Francisco Chronicle writer and author of “Game of Shadows: Barry Bonds, BALCO, and the Steroids Scandal That Rocked Professional Sports.” Pick up a copy if you don’t already have one. How are book sales on that one, Lance?

Williams: I’ve been really pleased. They’ve sold a couple of hundred thousand hardbacks in the last year and a half, and that’s 10 times as many as I ever thought.

Harris: I want to talk to you off-air about a loan, by the way.

Williams: I wish you made more money selling books. Unfortunately, it’s more of a labor of love. I’ve just been happy with the experience. So there you are.

Harris: All right. Thanks for spending time on Truthdig, and maybe we can check in as the trial gets under way.

Williams: My pleasure.

Harris: All right, Lance. For Lance Williams, this is James Harris, and this is Truthdig.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.